Historically First

Summer 2020

Trailblazing women led the way and made history as the first in their fields.

BY MEGG MUELLER

The importance of women to Nevada’s history is well documented and irrefutable. From Sarah Winnemucca to Helen Stewart, Hanna Clapp to Felice Cohn, the sisters of the Silver State left their own indelible stamp on the face of Nevada. While many women have made their mark, a select few were the first to do so in their respective fields. These pioneers broke the rules, and often, the glass ceiling that existed for women by becoming the first female to accomplish what they did. These women—and to be sure, there are many others—helped pave the way for more women to enter the workforce and seek positions that had been previously dominated by men.

These leading ladies took the chance to go where no woman had gone before, and for that, they are our favorite firsts.

WRITING THE WRONGS

The battle to keep the history of Native Americans alive was a lifelong one for Sarah Winnemucca. She was born in 1844 near Humboldt Lake in Churchill County, and she didn’t see a white person until she was age 6. Her grandfather, Chief Truckee, was chief of the Paiute tribe, and he welcomed the white man’s arrival, but her father, Chief Winnemucca, was worried about how their arrival would change the lives of his tribe.

Winnemucca spent most of her life working to help the two races understand one another. In 1883, she delivered nearly 300 lectures in major cities of the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic about the injustice against Native Americans. In the same year, she became the first Native American woman to publish a book, and her story “Life Among the Paiutes: Their Wrongs and Claims” told the history of the Paiutes and her own life story.

A WOMAN’S PLACE IS IN THE HOUSE (AND SENATE)

On Election Day 1918, the “Nevada State Journal” did something unprecedented: The newspaper endorsed a female candidate for the State Assembly. No woman had ever served in the Nevada Legislature and in fact, women were not allowed to vote in state elections until 1916.

The Reno paper noted Republican candidate Sadie Dotson Hurst “has taken an active part in public matters” and assured that her experience in club work “will stand her and the people of Nevada in good stead should she be elected to the assembly.” The voters agreed, and Hurst became one of Washoe County’s seven representatives for the 1919 session.

Hurst was born in Iowa in 1857 and moved to Reno with her two sons after the death of her husband. In Reno, she became involved in women’s civic clubs and community improvement projects, both hallmarks of the Progressive movement.

Her preoccupation, however, was Prohibition. Hurst used political persuasion to stop the sale and consumption of alcohol. In those days Reno was known for easy divorces, championship prizefights, and back-alley card games. But the public’s interest in moral reform and concern about supplies during World War I (grain was better used for food than booze, ran one argument) were strong during the 1918 election. Reno-area voters elected an entirely “dry” delegation, including Hurst, to the legislature.

Hurst’s successful bills included one that raised the age of consent from 16 to 18 years and increased the penalties for rape. Similar legislation had failed in previous sessions. Her bill outlawing animal cruelty was also approved and both houses passed Hurst’s measure requiring the registration of nurses. Governor Emmet Boyle vetoed the measure because it did not specify standards.

In 1920, Hurst was asked to preside over the house during the passage of the resolution to ratify the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote. She ran for re-election in 1920 but was defeated in the primary. Since Hurst’s term, every Assembly but three has included at least one elected female legislator.

Frances Friedhoff was a Yerington rancher who became Nevada’s first female state senator in 1935. Friedhoff was not elected, but was appointed to replace her husband, George Friedhoff, who had resigned to take a job with the Federal Housing Administration. She was sworn in as the senator from Lyon County on March 16, 1935. Because the session was nearly over, she sat in the legislature for only 14 days, and her senatorial tenure lasted just over seven months.

She chaired the Senate Committee on Public Lands, of which her husband had been a member. In legislation, Friedhoff had a perfect success rate: Her only bill, which granted industrial insurance to Nevada Emergency Relief Administration workers, was passed.

Friedhoff declined to run for her seat in 1936, instead choosing to run the family ranch in Yerington. It would be another 30 years before a woman was elected to the Senate.

The first woman elected to the State Senate was Helen Herr of Las Vegas in 1966. No stranger to the state legislature, Herr served in the Assembly during two terms, 1957-1961 and from 1963-1966. Herr sponsored legislation to protect the interests of women, reform the state’s prisons, and expand mental health care in southern Nevada.

One of her most important pieces of legislation was a 1973 bill that guaranteed equal pay for equal work for men and women. Herr served in the Senate until 1976 and was the first woman elected to the Senate Hall of Fame in 1993.

Bernice Martin-Mathews became the first black female legislator in the Nevada State Senate in 1995. She served as the assistant minority leader and was on the committees for finance, legislative operations and election, and natural resources. She served until 2010 and was inducted into the Senate Hall of Fame in 2013.

Patricia D. Cafferata, known as Patty, was a member of the Nevada State Assembly from 1978-1982. In 1982, Cafferata was the first woman elected to the office of State Treasurer, which she served as until 1987.

SHE’S THE LAW

In 1919, George Crowell, the highly respected and elected sheriff of Lander County, died from an illness. With two years still left on his term, the citizens wanted his wife Clara to finish his term. A petition was quickly circulated, and the commissioners followed suit, making Clara Dunham Crowell the first woman sheriff in Nevada history.

The “Reese River Reveille” reported, “There were several male aspirants for the job, but none made a formal application after the petition was circulated and presented to the county commissioners.”

Clara proved she could handle any situation and was involved in the apprehension of cattle rustlers, horse thieves, robbers and other criminals. As sheriff she demanded respect for the law in Lander. She and her deputy even enforced the new Dry Law which, among other things, prevented people from transporting bottles of liquor.

“The Dry Law has been looked upon as more or less of a joke,” reported the “Reveille.” “The officers are making a drive to show that the law, be it good or bad, must be respected.”

Sheriff Crowell was a woman of action. Once she posed as an old Native American to catch a man who was selling liquor illegally. After catching the storekeeper in the act, Clara threw open her coat, exposing her badge, and placed the man under arrest. On several occasions she entered saloons and broke up brawls and earned a reputation as a tough law officer.

When her term came to an end, people encouraged her to run for election. But she put her nursing skills to work as administrator of the county hospital, a position she held for 20 years. When she died at age 66 on June 19, 1942, a great tribute to both Clara and George was made in Austin.

GAME FOR THE CHALLENGE

“Anybody who lives here is out of his mind.”

That’s the first thing Mayme Stocker said upon moving to Las Vegas in 1911.

Following her husband Oscar across the country as his railroad job kept them on the move, Stocker was used to new places but seeing Las Vegas left an indelible mark on her. With three sons in tow and tired of moving, the family vowed to make the new town their home.

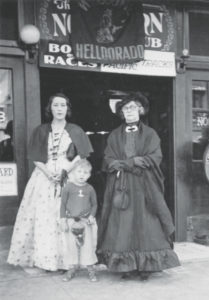

Stocker opened the Northern Club on Fremont Street in 1920. The club was a “soft-drink emporium” but it was also a place to play the five cards games that were legal at the time— stud, draw poker, lowball poker, 500, and bridge. The club was in Mayme’s name, because according to his son Harold, the “railroad men weren’t supposed to have anything to do with things like that” so his wife held the license. Harold had learned to deal cards and his brother Lester was a professional gambler, so it was a family business from the beginning.

When gambling was legalized in 1931, Mayme Stocker had Las Vegas’ first gaming license.

When her husband died in 1941, Stocker turned the business over to others, and in 1945, she leased it to Wilber Clark who eventually founded the Desert Inn.

THE DANCING MAYOR

North Las Vegas in the early 1950s was a tough town for any politician to run, but for a politically inexperienced ex-Ziegfeld showgirl to slip into the city council, straighten out the town’s tangled finances, and then become a tough, innovative mayor didn’t seem possible.

Dorothy Porter made it possible, and she was the state’s first woman to run a major city. She took office in 1954, when a woman in politics was still almost unheard of. A dancer, actress, and a pretty blonde, critics disparaged her as a burlesque queen, expecting her to collapse under pressure. They didn’t know Porter.

Porter and her husband moved to North Las Vegas in 1949, when the untamed town was a haven for bars and brothels. The Porters bought a motel near the newly opened Nellis Air Force Base but were consistently harassed by illegal brothel owners to sell the property. During this time, her husband died and Porter was ready to give up, but seeing that the influx of bars and brothels were further downgrading North Las Vegas, she got angry and decided to fight.

“When I wouldn’t sell, some so-called official told me my motel did not comply with building standard. Or that something was wrong with the water supply system or even that the trees were too close. I spent a lot of time going over the city book and found there were no restriction. It was then that I determined to do something about the system in North Las Vegas.”

She ran for city council in 1953, and won, defeating three male candidates. Her opponents waited for her to reveal herself as a dumb blonde, but what they found was a woman with considerable financial and business acumen. Her colleagues wasted no time in appointing her finance commissioner and vice president, and she set about putting in order the city’s finances.

Less than three years later the “North Las News” could boast that the city was “in as sound a financial shape as any city in Nevada.”

In January 1954, the city was rocked by the indictment of the mayor and three council members by the Clark County grand jury on charges of malfeasance. Porter was left to carry on most of the business of government. By late summer of 1954, new council members had been named, and after the resignation of Mayor Earl Webb, the new council elected Porter mayor.

Mayor Dorothy, as she was called, started initiatives to get a water system, a post office, paved and lighted streets, and playgrounds for children, and she fought to get money to help the city grow. Porter saw to the building of the most modern city hall in southern Nevada, a fire and police station, and a new water works, including a three-million-gallon reservoir and flood control system.

By May 1956, Porter was glad to retire.

“I had done what I set out to do. The budget was balanced, and the new city hall was being built. It was time for me to go home, salvage my marriage, and return to my own life,” she said.

And she did. In 1959 John Porter was appointed deputy to Attorney General Roger Foley, and Dorothy went with her husband to Carson City. She continued to support the Las Vegas Convention Center, which had opened that year. She is named on the commemorative plaque that is placed at the center.

MORE ROLES TO PLAY

From sheriff to mayor, senator to gaming operator, women in Nevada were pioneers in their fields from the earliest days of statehood. Since that time, the novelty of women in positions of power and authority has worn off, as there is hardly a profession or aspiration that is solely the domain of men. In fact, in Nevada’s 80th legislative session in 2019, 32 women held seats in the Assembly and Senate, making it the first female majority legislature in the U.S.