Locomotives Calamities

September – October 2018

Nevada has seen its share of railroad tragedies, many of which produced deadly results.

Nevada has seen its share of railroad tragedies, many of which produced deadly results.

BY ERIC CACHINERO

PHOTOS PROVIDED BY NEVADA STATE RAILROAD MUSEUM, CARSON CITY

During the night of Oct. 1, 1903, on the Southern Pacific line near Beowawe, The Atlantic Express and No. 219 trains barreled down the tracks; one headed east, one headed west, respectively. The only problem with this seemingly normal scenario was that the trains were on the same track, heading not in opposite directions, but directly toward each other. In the dead of night, two gigantic hunks of metal weighing thousands of tons and traveling at high rates of speed, collided head on.

The “Daily Californian Bakersfield” reported the horror: “The concussion was so great when the trains collided, that the passenger coach telescoped the smoking car for half its length. The engines are now locked together.

Mr. [Alan] Harper was sitting in the rear end of the smoker and was pinioned in the wreckage being horribly mangled. Death was not instantaneous but nearly two hours were consumed in extricating the body. Many remarkable escapes from death are told of by passengers.”

Alan Harper was the only casualty in the crash, though 20 more were wounded. Unfortunately, many Nevada train wrecks produced much-deadlier results.

May the tragic stories of these pioneer men and women of Nevada and the West never be forgotten. Their stories are not insensitively recounted here for entertainment, but rather to acknowledge and commemorate some of the tragedies that shaped the state, and led to Nevada becoming what it is today.

BEOWAWE, SEPTEMBER 1905

Less than two years after the grizzly catastrophe in Beowawe, yet another collision took place in nearly the same spot. On Sept. 20, 1905, the “Salt Lake Telegram” reported, “Twenty-five persons at this hour (1:30 a.m.) are reported injured and one man, George Wareman, is dead, as the result of a terrible head-on collision on the Southern Pacific between two freight trains, followed by the rear-end collision between two passenger trains at a point 9 miles west of Beowawe, between 6 and 7 o’clock last (Tuesday) evening.”

What actually happened was initially somewhat hazy, but it was reported that Southern Pacific westbound train No. 3 became immobilized and stopped on the tracks. A flagman went back to place warning torpedoes (small, coin-sized explosives placed on the tracks that when run over would warn train engineers of danger ahead), but it’s believed that when the engineer of the approaching train ran over the torpedoes, he ignored their warning and crashed into the stopped train.

The “Telegram” added, “The engineer and fireman are reported among those injured, though this is not positively confirmed. Many more deaths are expected when complete details are in.”

The following day, the “Van Wert Daily Bulletin” updated the details, indicating that the injured count had risen to 42, and two people had died. The publication also shed more light on the incident, “There was a head-on collision between two freight trains. Flagmen were at once sent out, and stopped the first section of passenger train No. 3, bound west, and which contained the Pullman coaches. Train No. 3 was run in two sections, and before the flagman could get out and give a warming [sic] the second section crashed into the first section.”

DEETH, JANUARY 1907

On the night of Jan. 23, 1907, the westbound Southern Pacific train No. 5 derailed, sending its cars hurling over a high embankment. The derailment took place 1 mile east of Deeth, resulting in one dead and 25 injured. The sole victim, S. Hoskins, suffered a fractured skull.

The horror was recounted in an issue of the “Reno Evening Gazette,” “No. 5 left Wells at 10 o clock [sic], running about four hours late. Just before reaching Deeth, while running forty miles an hour, the baggage, smoker, chair car, diner, tourist, and three Pullmans left the rails plunged over a fifteen foot embankment and rolled over. Only the engine and an empty express car were left intact.

The chair car was forced from its tracks and clear of the right of way fully 100 feet from the track. The smoking car suffered most and it was here that Hoskins was killed.”

According to some reports, the wreck was the result of a faulty brake beam that fell beneath the car wheel, while others claim that the crash was caused by a broken rail.

“Everything was done to make the passengers as comfortable as possible, but owning to the intense cold, several suffered severely,” the article continues. “As soon as possible the passengers were transferred to another train and taken to Carlin, where they were fed and warmed. Six cars of the train of twelve are in fairly good condition and will make up part of the train on to San Francisco.”

GOLD HILL, OCTOBER 1934

Even the famed Virginia & Truckee (V&T) has seen its share of railroad mishaps. In October 1934, a heavy storm raged in the Gold Hill area, causing the derailment of a V&T train. The “Reno Evening Gazette” recalls the non-injury mishap, “The storm last week caused the derailment of the engine of the Virginia and Truckee railroad train at the Gold Hill crossing. Another engine from Carson was required to pull the engine back on the tracks. The only damage done was the tearing up of several ties. A gasoline truck, while trying to go around the stalled engine, sank into a sewer near the crossing and help from Carson City was required to remove it.”

PALISADE, FEBRUARY 1911

“TWENTY-TWO INJURED IN WRECK.” “SCORES GAZE ON DEATH.” “OVER AND OVER CARS ARE TURNED DOWN EMBANKMENT AND ONLY STOP ON BRINK OF HUMBOLDT RIVER WHERE ANGRY WATERS HIDE AWFUL DEATH.” These are just a couple of the flamboyant and possible hyperbolic headlines presented by “The Bellingham Herald” of Bellingham, Washington, when describing the crash that happened on Feb. 20, 1911, near Palisade. It turns out the wreck was caused by a broken rail, which caused the Southern Pacific train to come crashing to a halt.

Once the dust had settled, the better-composed “Carbon County Utah” reported that, “Fifteen persons were injured in a wreck on the Southern Pacific near Palisade this state [sic] Monday night. One man and two women probably are fatally hurt, while twelve others were slightly injured. The wrecked train was No. 10, eastbound, known as the China Japan fast mail, and six cars left the track, three of which were hurled down the embankment.”

The paper also added, “That fifty or sixty persons were not instantly killed is a marvel, say railroad officials.”

PILOT PEAK, APRIL 1946

Even the comfort and safety of a person’s own home was not enough to stop railroad disasters, as evidenced by the events that took place in northeastern Nevada on April 6, 1946. The headline read, “DERAILED W. P. FLIER SMASHES NEARBY HOUSES TO KINDLING.”

“Smashing several nearby houses to kindling, the Western Pacific railroad’s eastbound Exposition Flier hurtled off the tracks in northeastern Nevada mountain country, leaving two passengers dead and 58 persons hurt today,” read an article in the “Ogden Standard-Examiner.” “A half dozen children were trapped in one house as one heavy coach ploughed into it, but they escaped with minor injuries.”

The crash took place about 13 miles west of West Wendover. Those who survived the disaster recount being tossed around their homes and showered with debris. In all, 10 coaches and one locomotive left the tracks, destroying three of the eight houses that were located at the Western Pacific loading point.

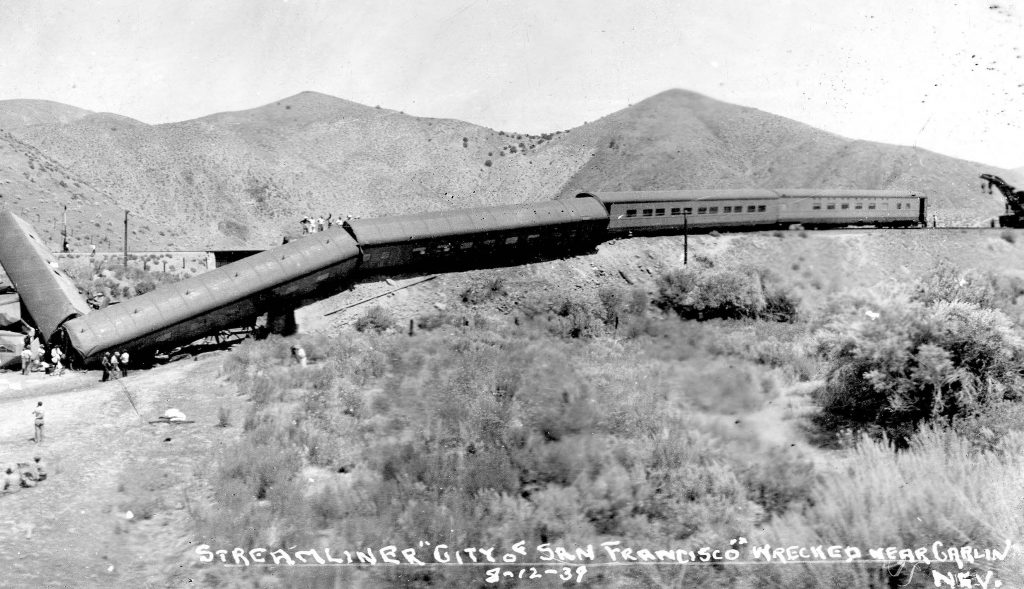

HARNEY, AUGUST 1939

Perhaps the most infamous Nevada train derailment took place just outside the town of Harney on the night of Aug. 12, 1939, and involved the illustrious and luxurious City of San Francisco. A 20-year Southern Pacific veteran named Ed Hecox engineered the famous train that day, and was pushing it to 90 mph to make up lost time.

Everything was going as planned until Hecox witnessed something was wrong as the train crossed the Number 4 bridge in the Humboldt River Gorge. The train hit a patch of rail that had been removed, causing the train to jump the tracks and sent it careening out of control down the embankment and into the river.

The “Reno Evening Gazette” painted the grizzly scene, “Twenty persons are known to be dead as a result of the worst train wreck in the history of Nevada, forty miles west of Elko on the Southern Pacific main line last night at 9:33 o’clock. Seventeen of these bodies have been recovered and three are visible but cannot be moved until cars are taken from the river bed of the Humboldt River. Five cars were piled in jumbled mass, where the bridge gave way. One of these rested upon a victim whose arms were visible, but it was impossible to remove him. Parts of bodies were strewn along right-of-way and victims were so badly mutilated that identification remained impossible in many instances.”

In all, the crash claimed the lives of 24 people, and injured 121. The event was seemingly a freak accident, though the official report quickly became that it was no accident, but sabotage. Investigators maintain that the rail had been cut, pushed in about 4 inches, and re-spiked.

They also discovered tools that were used in the act, essentially proving that the catastrophe was deliberate.

In response to the tragedy, Southern Pacific issued a $5,000 bounty, which was eventually upped to $10,000, though no one has ever come forward with any information leading to the arrest of the saboteur.

The case remains a mystery to this day. Whispers remain of a conspiracy cover-up claiming that the Southern Pacific knew the engineer was operating at an excessive rate of speed, though it’s possible that the world will never learn the truth. Regardless, there’s also been whispers that the Southern Pacific (now absorbed by the Union Pacific) would still honor the bounty if the case is ever solved.

KEEP CHUGGING

The idiom “like watching a train wreck” is accurate.

Train wrecks are violent, chaotic, and deadly most of the time; and although rare, when they did happen, oftentimes the events were so severe that they seared themselves in our memories forever.