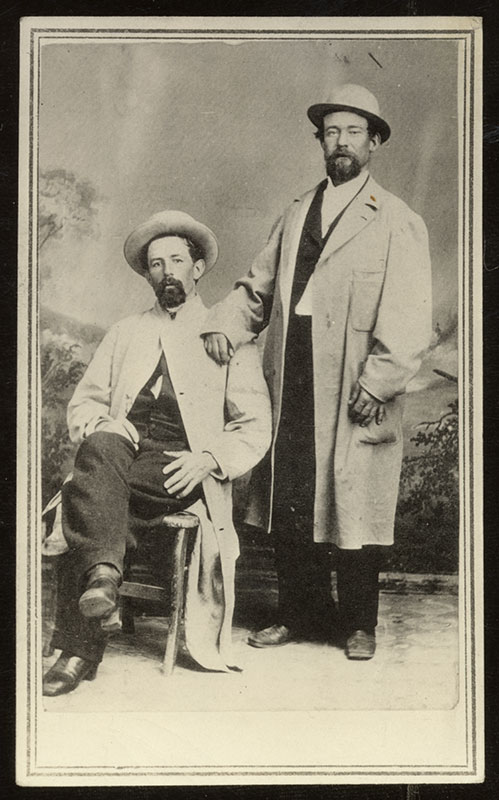

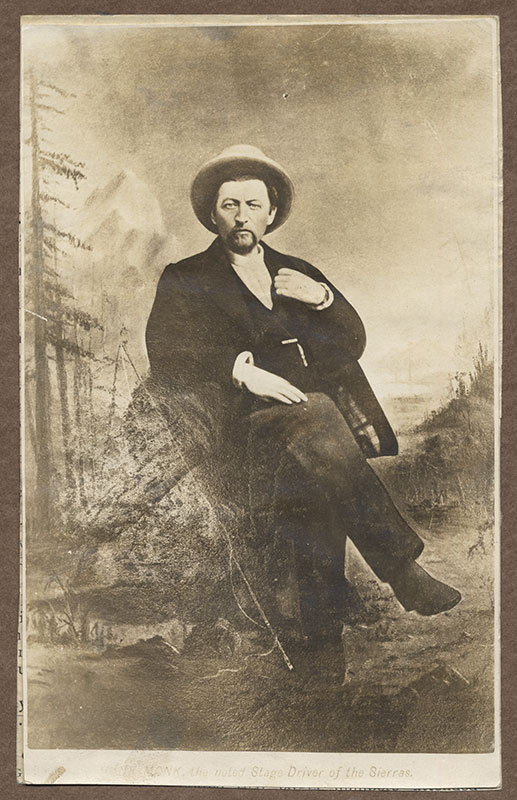

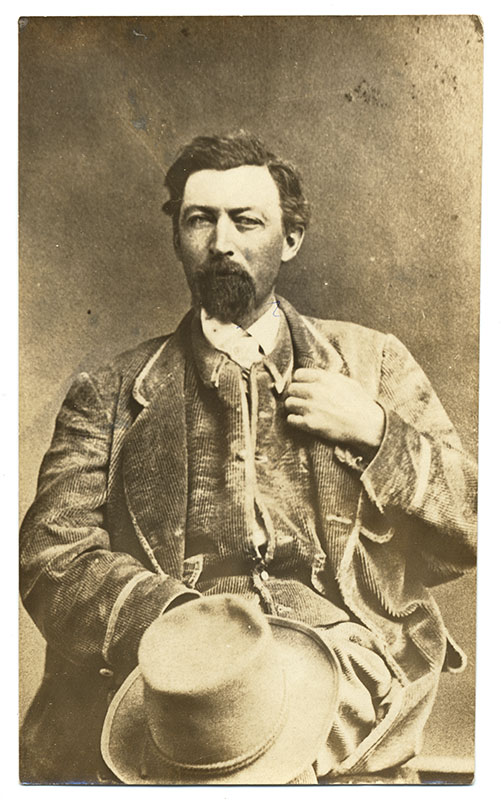

Hank Monk, The Incomparable

September-October 2017

BY BRANDON WILDING

“Hank Monk, the incomparable! The most daring – the most reckless of drivers; and the luckiest. The oddest, the drollest of all the whimsical characters who made Western staging famous the world over… It was a dream come true! I’m quite sure that had anyone asked me which of the two I would rather see – hear – speak to, Hank Monk, or the President (and that I mean Abraham Lincoln), it would have been the former I unhesitantly would have chosen. Without a doubt my youthful judgment was bias, but the fact remains.” —Idah Meacham Strobridge (“The Land of Purple Shadows”)

KNIGHT OF THE LASH

Henry James Monk was born in Waddington, New York circa 1832. Hank, as he came to be known, was the eldest of the four children of George and Polly Monk. From an early age he took to horses and had a natural way with them. It is rumored that he once drove eight horses abreast during a civil celebration.

At a young age, Hank landed his first job driving a stage. Some historians say that he may have been as young as 12 years old; others say that he was a little older. Nonetheless, they agree that he got into the business of stage driving at a tender age. He was given a regular route between Waddington and Massena, and the 20-mile route showed many of his doubters—who believed that he was too young—that he was a natural.

In 1849, like many young men in the country, he caught gold fever and hoped to travel to the goldfields of California to find his fortune. However, Polly Monk, like many mothers of the time, refused to let her son go west. Hank remained obedient to his mother for a few more years, but in 1852 he could no longer contain his fever for adventure.

It did not take him long to get a job when he arrived in Sacramento. With skills such as “turning a six-horse coach at full gallop with every line loose” he began driving a six-horse coach in the Sierras between Sacramento to Auburn, and then later Sacramento to Placerville with the California Stage Company.

In 1857, he made his way to Nevada and began to drive a route between Genoa and Placerville with the Overland Stage Company. He would spend the next 25 years driving the Carson City-Virginia City run and the Carson City-Glenbrook run with the famous Pioneer Stage Company, living in the St. Charles Hotel in Carson City during this time.

The legend of Hank quickly spread across the west. His charm and stories led to many famous men in his coach, including Union Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman and President Rutherford B. Hayes, though, nothing would make Hank Monk more famous than a day spent with Horace Greeley.

JEHU

On July 30, 1859, Horace Greeley, editor for the “New York Tribune,” was in Genoa running late for a speech that he was meant to give in Placerville. Turning to Hank Monk, his stagecoach driver, he asked if it would be at all possible to get over the Sierra Nevada Mountains in time for his speaking engagement. Hank put Greeley’s fears to rest and assured him that we would get him there on time. The rest is not only Nevada history, but American history.

As the story goes, the two men set off at breakneck speeds around dawn as Hank yelled out, “I’ll get you there!” The horses were pushed along the Carson River up to Hope Valley, then up over Luther Pass as Greeley bounced all around the coach and held on for his life. The two climbed Meyers Grade, over Johnson Pass, and into Strawberry to change horses.

Strawberry would have been the last telegraph station before they reached Placerville and Greeley was still worried about being late. Once again he asked Hank if they were going to be on time or if he needed to send a telegraph letting the people know that he was going to be late. Hank set off in another fury of dust and called back to his disheveled passenger, “I’ll get you there!”

Twelve miles east of Placerville, he unloaded his terrified cargo to the welcoming committee and proceeded to travel into Placerville. Later that day when Greeley met up once more with Hank he showed him his appreciation by buying him a new suit.

On Aug. 1, Greeley would telegraph the story of his adventure to the “New York Tribune.” The story became an instant success. While describing the ride of his life, he said, “Yet at this breakneck rate we were driven for not less than four hours or 40 miles changing horses every ten or fifteen, and raising a cloud of dust through which it was difficult at times to see anything.”

Hank would be interviewed about the famous trip for the rest of his life, and always seemed to embellish the story a little more each time. In one of those interviews he was quoted saying, “I looked into the coach and there was Greeley, his bare head bobbing, sometimes on the back and then on the front of the seat, sometimes in the coach and then out, and then on the top and then on the bottom, holding on to whatever he could grab.”

The story of the two men comically flying over the Sierra Nevada Mountains became one of the most retold stories west of the Rockies. Humorist Artemus Ward would retell the story, as would many other writers of that time. The story now mainly lives on in Mark Twain’s overly embellished telling of the story in “Roughing It.”

Whoever is telling the tale, there is no funnier image than that of Greeley yelling out in fear for Monk to slow down and Monk hanging over the stage and looking back to yell out, “Horace keep your seat! I told you I would get there by five o’clock, and by God I’ll do it, if the axles hold!”

RACONTEUR

Hank was known around the country for his great ability to drive a stage and his natural skills with horses and people. On the other hand, in the Carson Valley, Hank was known for another skill. He was a natural storyteller. He had great charm and a way of stretching the truth just far enough to still be believable. Nothing helps stretch a story more than a glass of whiskey, followed by a few dozen more. He wasn’t just a stage-man; he was a drinking man.

In Edward B. Scott’s 1957 publication, “The Saga of Lake Tahoe,” he joked, “Monk drank so much hard spirits that he often forgot what he was doing, when it came to incidental tasks connected with staging, and fed whiskey to the horses and watered himself, thus becoming accidentally sober enough to handle the inebriated team.”

Even though it would be frowned upon today, Hank was often carried from the saloon stool to his coach after drinking so much that his legs could no longer carry him. Once he was holding the reins, the whiskey never seemed to affect his ability to make his route in record time. And when the work was done, men at the next stop would carry him into the next saloon and listen to his great stories.

On one of those stops, he told the story about the day he was traveling to the top of Kingsbury Grade and was confronted by a robber. He was so surprised by the event, he threw the whiskey bottle that he was drinking from at the robber’s head, knocking him out. Hank climbed off his stage, gathered up his bottle of whiskey, put the robber in the stage and delivered his new passenger to the sheriff at Friday’s Station.

LEGEND

Henry “Hank” Monk died from pneumonia on Feb. 28, 1883. The legendary stage driver and drinking man was given a fitting obituary in the “Territorial Enterprise”: “Hank Monk, the famous stage coach driver is dead. He has been on the downgrade for some time. On Wednesday his foot lost its hold on the brake and his coach could not be stopped until, battered and broken on a sharp turn, it went into the canyon, black and deep, which we call death…”

Hank was loved by the people of the Carson Valley. It is said that he was kind to everyone and never spoke ill about any of his fellow man. The bar stools are a little colder in Nevada and the stories are a little less humorous without Hank Monk around.

THE ORIGIN OF JEHU

“And the watchman told, saying, He came even unto them, and cometh not again: and the driving is like the driving of Jehu the son of Nimshi; for he driveth furiously.” “2 Kings 9:20”

Jehu became a term of endearment for the stage drivers. Their jobs were dangerous, but often the stories were adventurous and glamorous. Whips like Hank Monk and Charley Parkhurst drove with a biblical fury and earned their titles.