Ancient Nevada Part V: Plants & Animals

September-October 2017

Fifth of six-part series explores the Great Basin’s primal flora and fauna.

BY ERIC CACHINERO

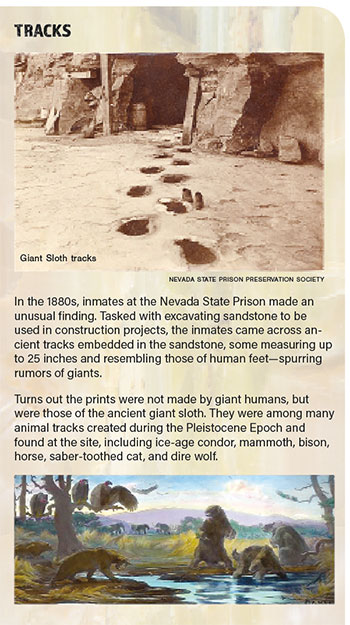

Tens of thousands of years ago, on a landscape marked by vast ancient lakes, a creature roved in search of prey. It stood about the same height as a male grizzly bear, and sported a set of scythe-like claws at the ends of its enormous hairy arms. Its massive jaws were lined with sets of stout teeth, which worked well when grinding its victims to mush. Flat feet and a stocky tail allowed the beast to stand up while wreaking havoc on its meals, which were sometimes located high above its head. But as menacing as this creature of yesteryear sounds, for the giant sloth—an herbivore—the only living thing that truly need fear it was a yucca or Joshua tree.

MEGAFAUNA

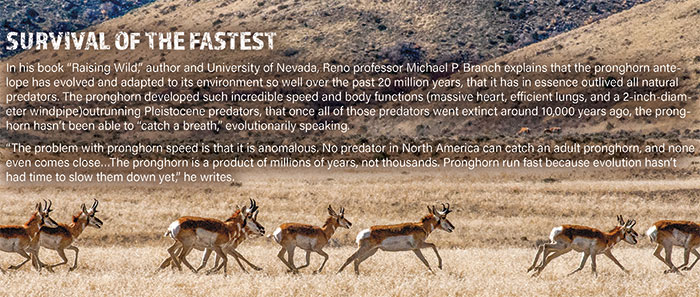

Everything was bigger back then. During the late Pleistocene Epoch (125,000-10,000 years ago), the land was ruled not only by violent volcanic eruptions, but the animals that inhabited the landscape. Megafauna is the term used to describe overly large animals, a commodity that was in no short supply in ancient Nevada. It’s not entirely clear why megafauna were so mega, but some sources suppose environmental factors and survival of the fittest to be contributing factors.

Everything was bigger back then. During the late Pleistocene Epoch (125,000-10,000 years ago), the land was ruled not only by violent volcanic eruptions, but the animals that inhabited the landscape. Megafauna is the term used to describe overly large animals, a commodity that was in no short supply in ancient Nevada. It’s not entirely clear why megafauna were so mega, but some sources suppose environmental factors and survival of the fittest to be contributing factors.

One such megafauna is the Columbian mammoth—a creature not requiring an introduction had you run into one during the time it roamed the earth. Standing 13 feet at the shoulders, weighing 22,000 pounds, and sporting tusks the length of a full-sized car, bands of these creatures fed and watered near the pluvial lakes of the past, and were occasionally unlucky enough to slip into an inescapable mud pit or watering hole. Mammoth fossils have been unearthed in both the northern and southern ends of Nevada, including the Black Rock Desert and Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument, respectively. The region surrounding the former was also home to large ice-age horses, whose remains met a similar muddy demise as those of the mammoth. Fossils of both of these creatures have been unearthed and now reside at the Nevada State Museum in Carson City.

Giant mammoths and horses weren’t the only megafaunas to call Nevada home, though. The scope of gigantic animal species in ancient Nevada was as large as the species that comprised it.

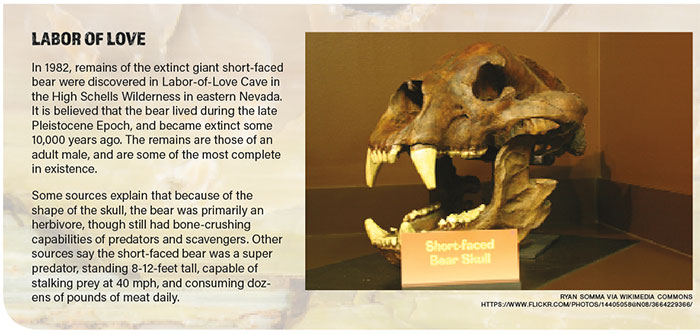

Mammals included the dire wolf—an extinct prehistoric carnivore and larger relative of the modern grey wolf, which fed on ancient horses, ground sloths, and other megaherbivores. Its closest competitor was the saber-toothed cat—a precision killing machine weighing several hundred pounds with fangs that measured up to 11-inches long. These two were some of the fiercest predators during the late Pleistocene Epoch.

Ancient bison (double the size of the modern species), giant camels, and an array of large birds, including condors were alive during the same period. Several sources also claim the presence of cave bears, hedgehogs, and rhinos in ancient Nevada. It truly was a different world.

FLORA

But animals weren’t the only things that were bigger back then. It was a world incomparable to that of present day; and plant life was thriving, especially before the most recent ice age began.

But animals weren’t the only things that were bigger back then. It was a world incomparable to that of present day; and plant life was thriving, especially before the most recent ice age began.

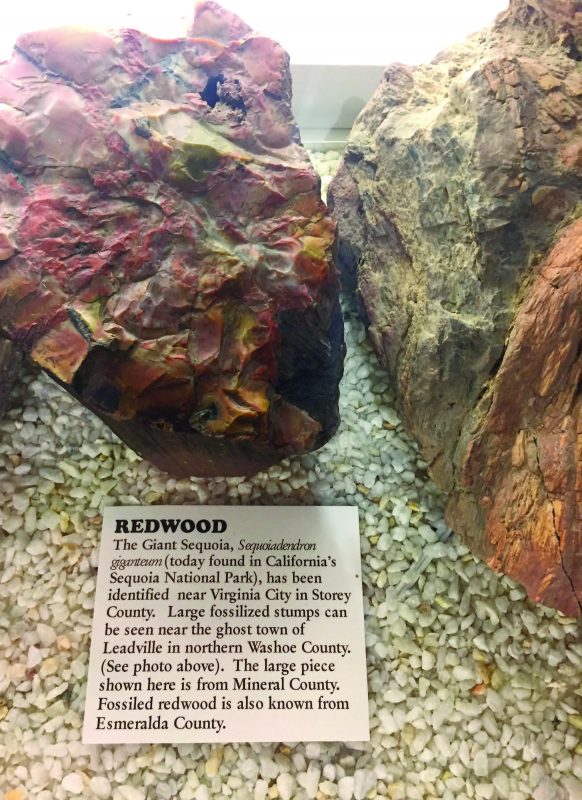

If you were to travel back in time—before statehood, before the discovery of the Com- stock Lode, and even before man ever set foot in what would become Virginia City—you may find yourself lost in unfamiliar woods. Groves of giant sequoias—commonly known as redwood trees—covered much of the areas that would become Storey, Washoe, Mineral, and Esmeral- da counties. Woodlands of different species also speckled the state, including oak and willow.

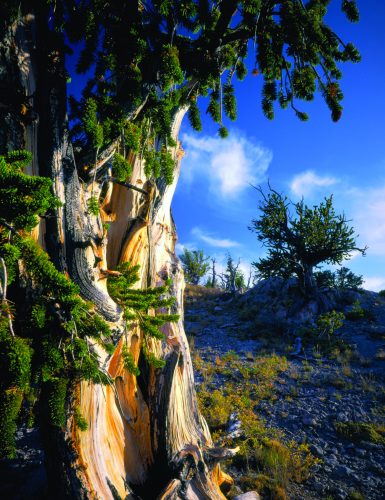

Today the fossilized stumps of these ancient trees give us a window to the past. Bristlecone pines—one of Nevada’s state trees—are believed to be some of the longest-living trees in existence. In 1964, geographer Donald R. Currey was researching ice-age glaciology on Wheeler Peak in eastern Nevada. To better understand the glacial features and how they affected the bristlecone pines, Currey was given permission from the U.S. Forest Service to take core samples of a specimen he believed to be more than 4,000 years old.

The specimen in question was known locally as Prometheus, and unbeknownst to Currey, his research would be the deathblow to the ancient tree. Currey took core samples using a borer, and although no one knows for sure what went wrong, many speculate that his tool broke off in the tree. Once the bristlecone died, he was given permission to cut it down to find out the true age of the tree.

Prometheus had 4,862 rings, though scientists theorized that rings might not have formed each year due to harsh conditions. Because of this, Prometheus was estimated to be 4,900 years old when it finally died. The stump is all that remains of the prehistoric plant. Since Prometheus, several older bristlecone pines have been discovered, with one confirmed to be more than 5,000 years old. The location of this bristlecone pine is being kept secret. Swamplands provided habitat for animals to thrive and hunt. Swamp Cyprus—much like that found in subtropical Florida today—was common in White Pine County near Ely. Similar swamp- lands existed in Tule Springs near Las Vegas and in Carson City. As time passed and these ancient swamplands began to dry, the common Nevada desert plants began to thrive. Sagebrush and juniper migrated and became more prominent in much of the state, as did the pinyon pine.

PRIMAL PRESENCE

Nowadays, most people are unaware of what occurred all around them so long ago. Daily commuters drive through ancient swamps and work in buildings that sit atop petrified ancient forests. Thousands of years ago, a giant sloth could have fought off a saber-toothed cat in the park down the street; a dire wolf could have nursed pups in your backyard; a Columbian mammoth could have relieved itself on the ground you currently stand on. You never know.

Next issue, we’ll explore the complex geology that makes up The Silver State.