Celebrate Lake Tahoe with the Nevada Museum of Art

September – October 2015

New exhibition spans 200 years of art in the Tahoe region.

BY JERI CHADWELL-SINGLEY

“Tahoe: A Visual History” opened at the Nevada Museum of Art (NMA) in August. Four years in the making, this huge exhibition fills all 15,000 square feet of gallery space in the museum and features many privately held pieces that are rarely on display to the public.

NMA senior curator and deputy director Ann M. Wolfe explains that amassing these artworks from across the country, and as far away as Europe, represents a truly historic moment for the museum and the public alike.

“When else will you see all of that material together in one gallery, one museum?” she asks.

Ann says the exhibition, which runs through Jan. 10, 2016, will help to give the region a presence in the larger world of American art, placing Lake Tahoe alongside the nation’s most famous backdrops such as Niagara Falls, the Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, and Yosemite.

UNDERSTANDING LAKE TAHOE THROUGH ART

The exhibition represents the first major survey of art from Lake Tahoe and the surrounding Sierra Nevada region. Featuring roughly 400 individual artworks created by about 175 artists, it allows visitors to explore the artistic and cultural significance of the lake through the eyes of the people who have come to its shores seeking sustenance and inspiration. The exhibition is divided among six categories that combine to create an in-depth narrative of this iconic landscape:

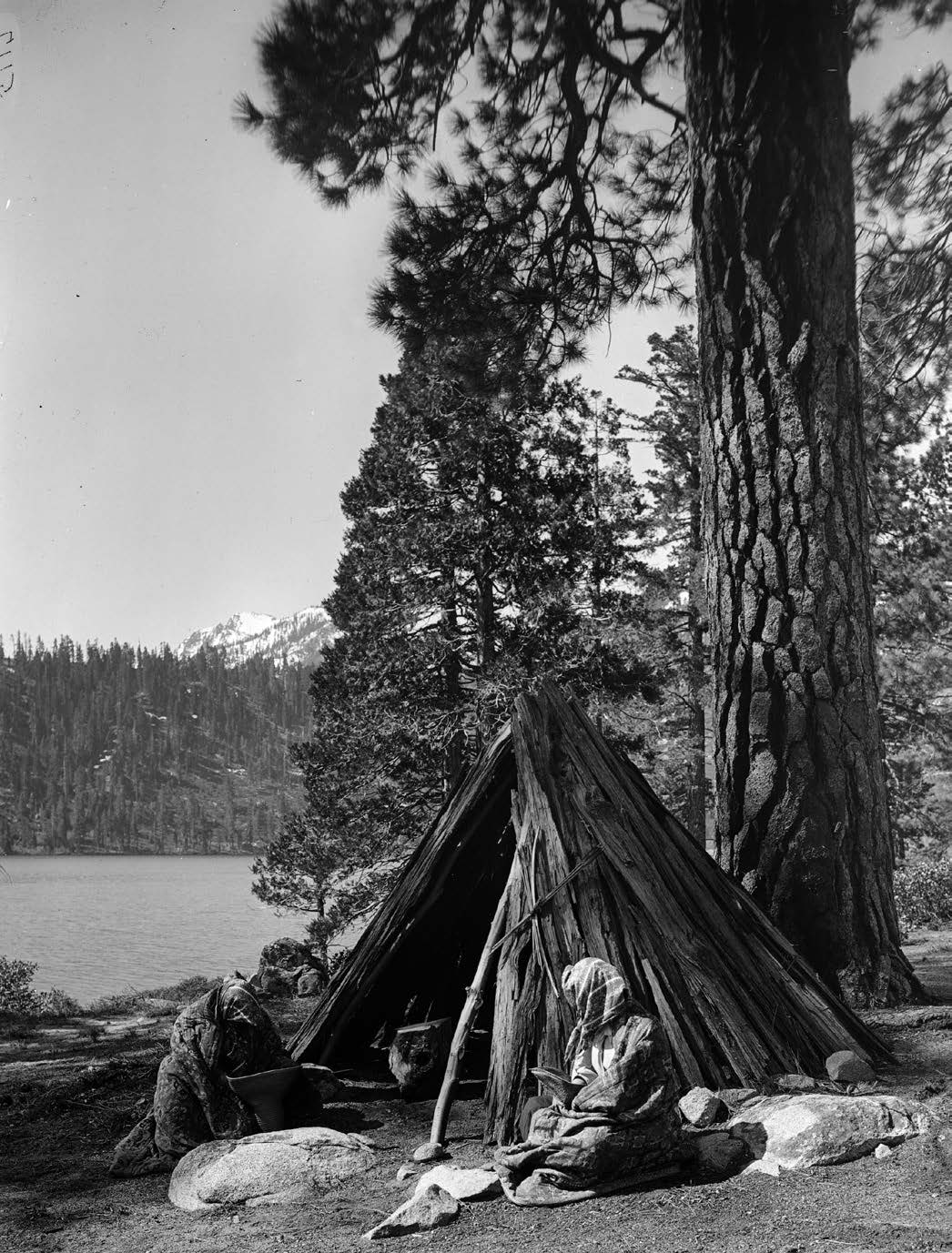

WASHOE BASKETRY — The Washoe people—the lake’s first inhabitants—called it Da’aw’aga, “the edge of the lake.” The natural fibers of the beautiful woven Washoe baskets on display not only tell a story of daily life—of food gathering and preparation and the carrying of everything from camp materials to children—they also tell the stories of the individuals whose skill and artistry went into their creation. The exhibition marks the largest ever assemblage of Washoe baskets, Ann says. Visitors will also gain insight into the commercialization of Native basketry during America’s Arts and Crafts Movement—a time when Tahoe’s native people were faced with many challenges brought on by the arrival of white settlers.

Featured: Louisa Keyser (Datsolalee), Scees Bryant, Lena Dick, Sarah Mayo

CONTEMPORARY ART — As a part of the exhibition, the NMA commissioned new works from 15 artists, including three pieces from Maya Lin—who is best known for having designed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. Visitors are able to explore the artists’ visualizations for the future of the lake, presented through a variety of media. Among Maya’s pieces is a large depiction of the Tahoe watershed created from straight pins. Visitors will find the work of Russell Crotty hanging from the gallery’s ceiling. Russell has created a 60-inch diameter paper-covered Fiberglas sphere bearing a pencil and watercolor ink depiction of Nevada’s shoreline from the coves just north of Glenbrook. Ann says visitors will enjoy the almost fish-eye lens perspectives of oil paintings by local South Lake Tahoe resident Phyllis Shafer. Among Phyllis’ pieces is a large-scale painting that offers a panoramic view of the lake that can only be seen in real life by climbing to the top of Cave Rock on the lake’s eastern shore.

Featured: Maya Lin, Chester Arnold, Lordy Rodriguez, Nick van Woert, Phyllis Shafer

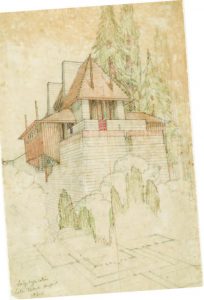

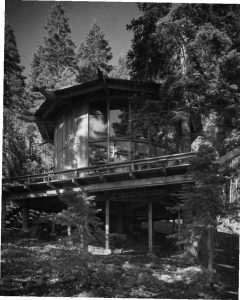

ARCHITECTURE — The impact of the Arts and Crafts Movement on Lake Tahoe can also be seen in the architecture of some of its buildings. From the Bow Bay estate, designed by Julia Morgan—the architect responsible for Hearst Castle—to Frank Lloyd Wright’s imagined Lake Tahoe Summer Colony in Emerald Bay, the exhibition celebrates the work of architects who have drawn inspiration from the lake’s scenic vistas and sought to mirror its natural majesty in their creations. Ann says visitors will enjoy seeing drawings, postcards, and a model of Frank’s proposed Summer Colony, as well as other pieces demonstrating the diversity of Lake Tahoe architecture.

Featured: Frank Lloyd Wright, Bernard Maybeck, Julia Morgan, John Maniscalco, Frederic DeLongchamps

PAINTING — Paintings from more than 60 artists are featured in the exhibition, including several depicting Donner Lake and other striking scenes from the Sierras. According to Ann, it was a common belief during the 19th century that nature could convey the presence of a higher power, and artists of that era often strove to capture this by painting in the midst of dramatic landscapes. But Tahoe itself, she says, has always been a challenge for artists to depict. For some painters, the vast, serene, panoramic landscape did not always provide a fitting subject, and many preferred the more striking mountain views of Donner Lake, where the crossing of the summit was a symbol of the last great challenge to America’s Manifest Destiny. These paintings greatly romanticized the area, rarely depicting the human costs associated with western expansion—costs borne heavily by the Chinese laborers who built the railroad that made this crossing possible. Set among the historical paintings, visitors will find pieces from contemporary Chinese and Chinese American artists whose works, Ann says, help to revise this history by incorporating the Chinese narrative.

Featured: Albert Bierstadt, Zhi Lin, Maynard Dixon, Mian Situ, Marianne North

HISTORICAL MAPPING — According to Ann, Lake Tahoe has actually gone by several different names in the past—Mountain Lake, Lake Bonpland, and Lake Bigler. Located on the very western edge of the Great Basin, the lake was among the last places to be explored, charted, and mapped by Euro-American explorers. The first of these explorers to lay eyes upon Lake Tahoe were John C. Frémont and Charles Preuss, who—in the company of Kit Carson— looked down upon it from a mountaintop as they navigated what is now Carson Pass. Sketches, journals, and maps allow visitors to reflect upon the early explorers’ impressions of the lake and surrounding region.

Featured: John C. Frémont, Charles Preuss, John Muir

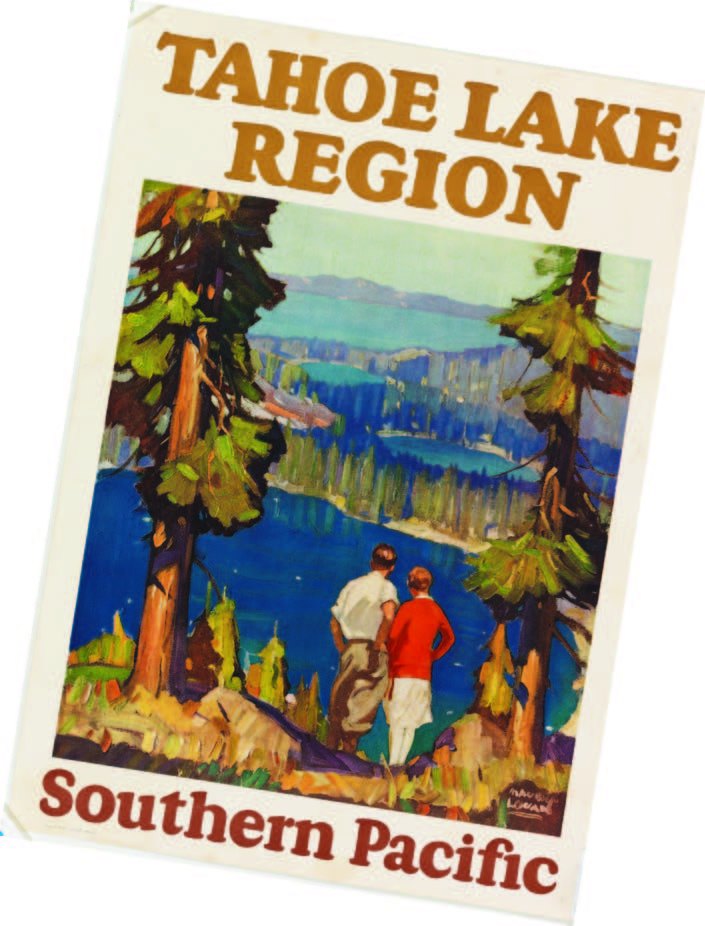

PHOTOGRAPHY — The exhibition includes 150 years of Lake Tahoe photography. According to Ann, early photography of the lake was often done as a part of government surveys or on behalf of railroad companies or commercial firms. She says that even after the development of roads in the area made accessing Lake Tahoe easier, many photographers still chose to shoot in locations like Yosemite and Yellowstone. Available notes, Ann says, suggest that Ansel Adams’ photos of Lake Tahoe were taken when the artist was just passing through. In the second half of the 20th century, photographers became increasingly interested in the lake; much of this later work is focused on issues like environmentalism, private

development, and lake tourism. Visitors will enjoy comparing and contrasting early photography of the area and contemporary pieces that often demonstrate Lake Tahoe’s altered landscape.

Featured: Ansel Adams, Anne Brigman, Elizabeth Carmel, Peter Goin, Eadweard Muybridge, Carleton Watkins

MORE THAN AN EXHIBITION

“Tahoe: A Visual History” is an exhibition of truly epic proportions, one that visitors will likely want to return to several times over the coming months.

“There’s just so much to take in,” Ann says. “If it were me, I’d probably come three times, maybe four.”

And it’s more than just the exhibition that merits multiple visits. The museum is also offering a host of public programs through the third week of January, including special events, talks, classes, and guided hikes presented in partnership with the Tahoe Rim Trail Association; these hikes will reveal highlights about artworks in the exhibition and the artists who created them. Additional information can be found in the events calendar on the NMA website. Out-of-town visitors and locals will be happy to know that they can take a part of the exhibition home with them to keep. The “Tahoe: A Visual History” book is a 500-page, hardbound companion piece to the exhibition. Authored by Ann—with contributions from eight prominent scholars—the book offers beautiful color photos of the exhibition’s artworks placed alongside information rich chapters about the artists and the lake’s history. The book is available for purchase at the museum, in area bookstores, and online through Amazon.

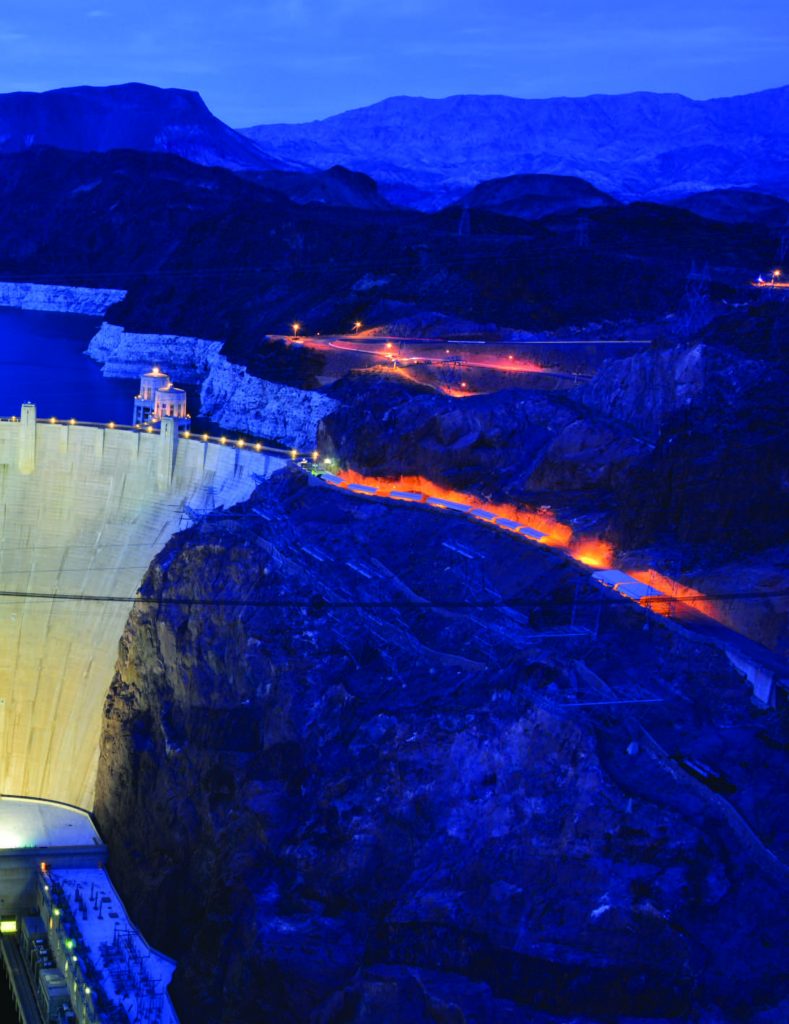

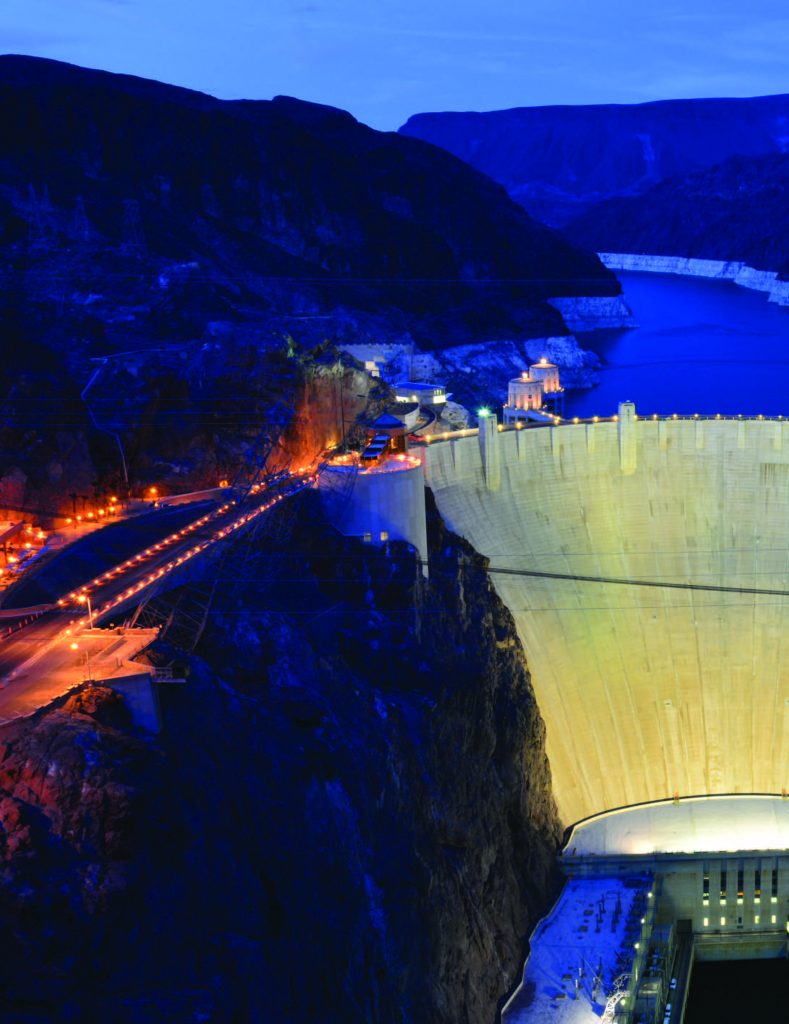

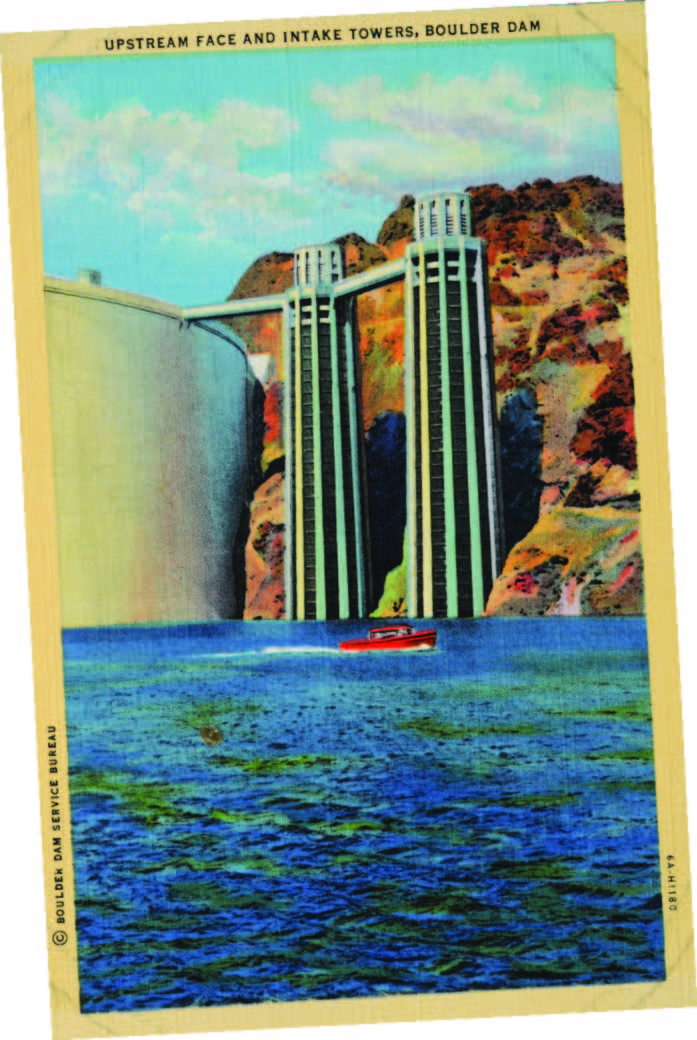

Hoover Dam

America’s Greatest Construction Feat Remains a Marvel.

BY MEGG MUELLER

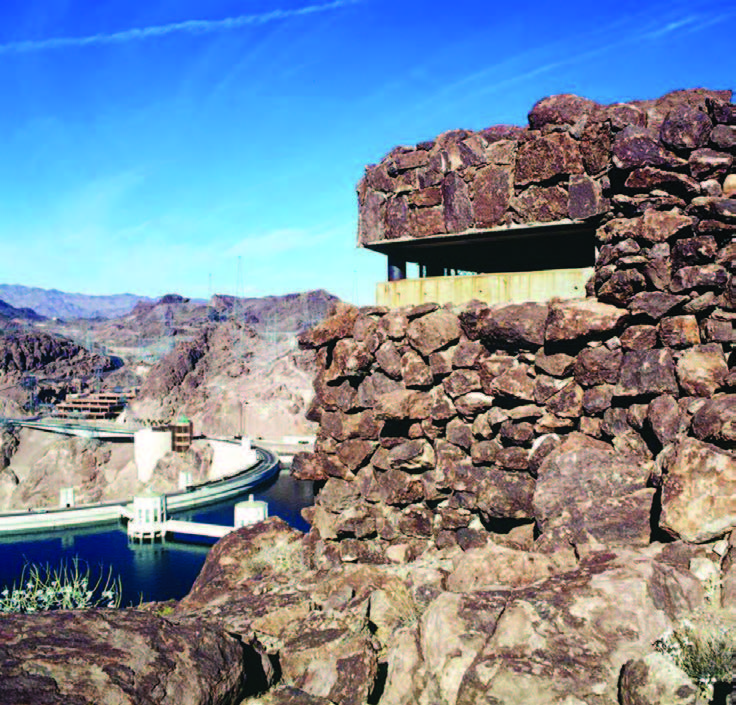

On Sept. 30, 1935, Hoover Dam was officially dedicated. For eight decades, this bastion of American ingenuity has stood sentinel over the Colorado River, keeping its waters consistent, calm, and constructive. Its story has been told time and again; its facts revealed, its impact explained, and its legend recounted. But we can never get enough, as evidenced by the approximately 1 million people who tour the dam each year. There are many moving parts to the story of Hoover Dam; here are but a few.

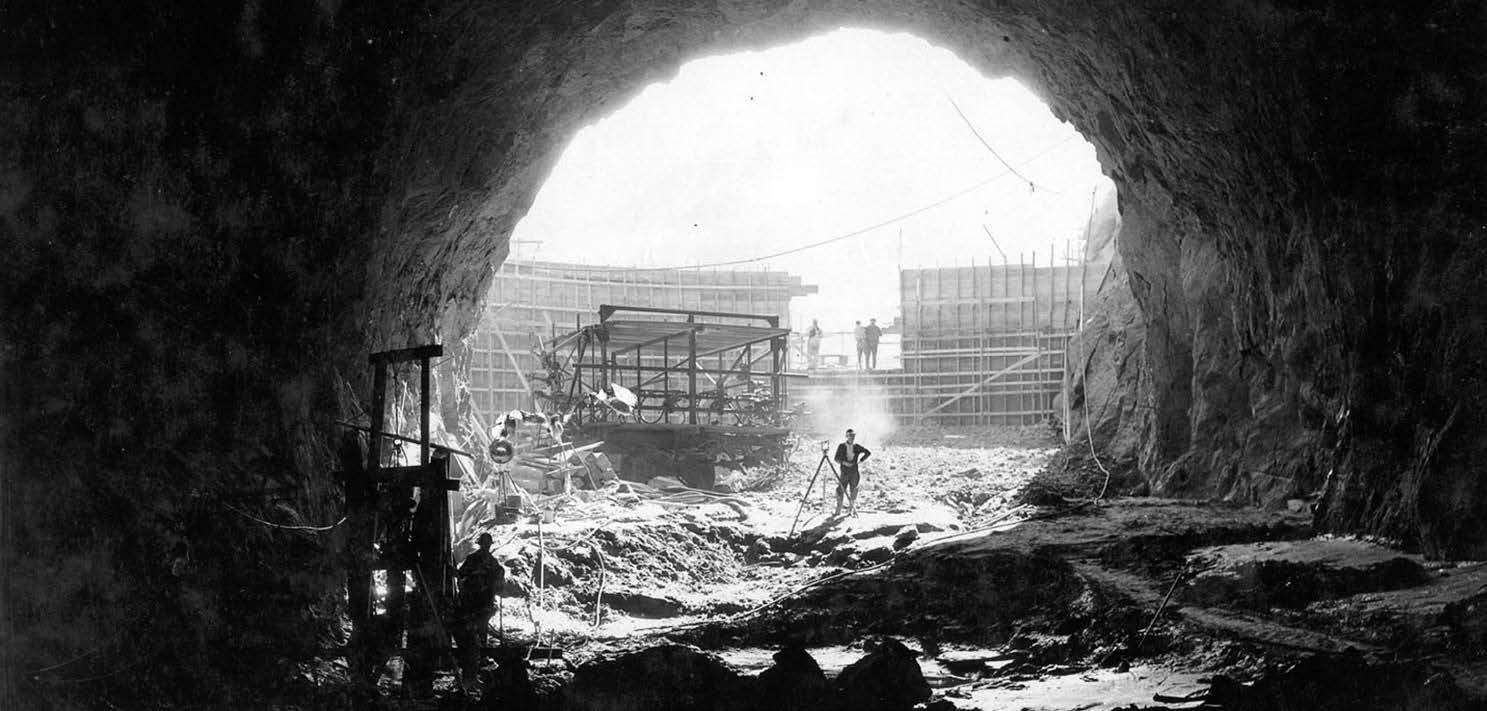

WORKING FOR THEIR LIVES

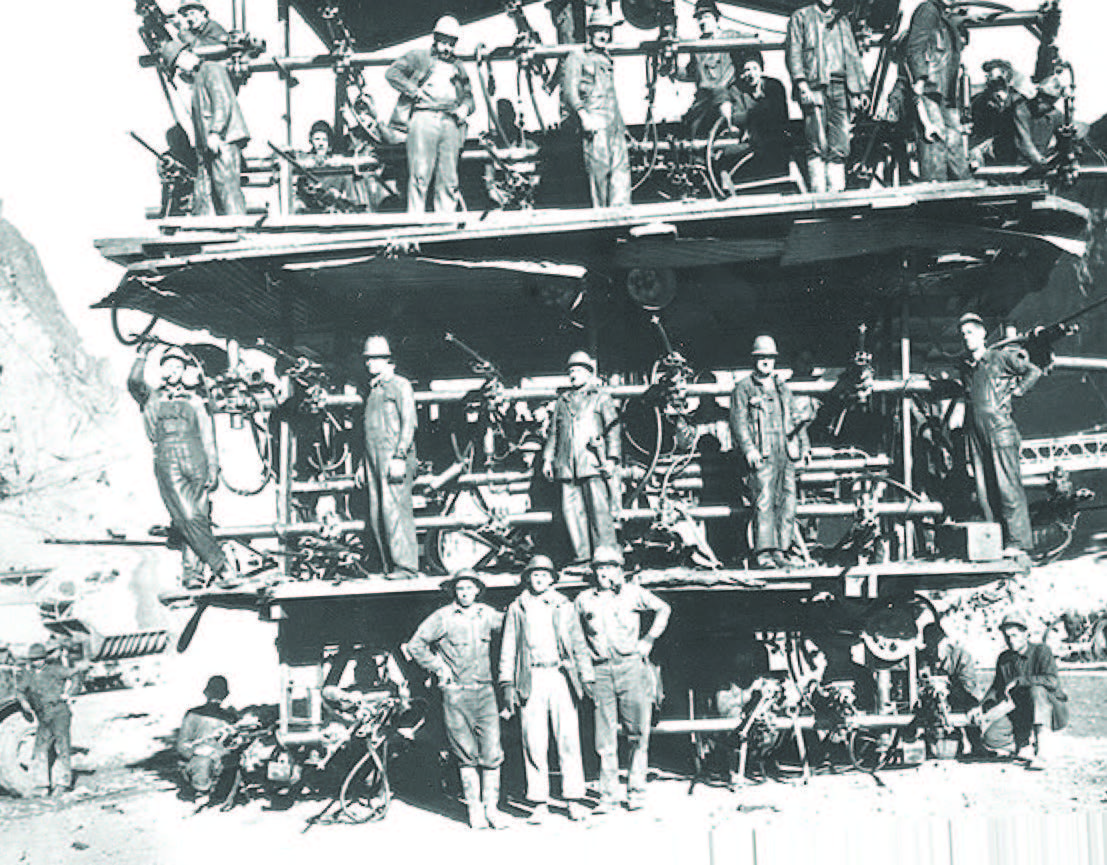

For most of us, Hoover Dam has always existed. But in 1931 when construction began it was merely a dream, and for many of the workers, a much-needed paycheck on the heels of the Depression. Thousands of workers flocked to the area in the hopes of gaining a steady income and to be a part of the monumental task ahead. The Bureau of Reclamation notes 21,000 men worked on the dam in total, with an average daily total of 3,500 workers.

G.C. “Buck” Blaine told Nevada Magazine in 1985 he came to work on the dam in 1931 for what he thought would be an easy, well-paid engineering job. He wasn’t alone in that thought; there were nearly 100 applicants for every job. Buck worked as a highscaler—workers who drilled holes in the canyon wall while suspended 700 feet above the river—because it paid a dollar more a day than mucking. (Visit nevadamagazine.com/hoover to read about Buck and four other dam workers from our 1985 May/June story.)

The often dangerous conditions have led to tales of thousands of deaths, and even that men were buried within the walls. According to the Bureau of Reclamation, 96 deaths are attributed to work-related incidents during construction, and no bodies were left inside the walls. The last-known dam worker—identified by museum records as reported by the Boulder City Review—died in November of last year.

A TOWN OF THEIR OWN

For some workers, the pay also included room and board at the federally created town of Boulder City. The government knew it needed a place to house the men and women who came to work on the dam, and Boulder City—eight miles from the dam— was built to house 5,000 workers.

The Boulder Theatre was built in 1933, and because it was the only air-conditioned building in town, dam workers would buy a movie ticket just so they could sleep in the cool air. Designed as a place of clean living and family values, Boulder City banned gambling from the onset, and was built with numerous parks and plenty of centralized public space. Despite a preponderance of young, single men, Boulder City easily retained its innocence as workers looking for more varied pursuits were able to take a train 26 miles to Las Vegas.

Today, the population is about 15,000, but the town still fiercely preserves its small-town feel, and is one of only two towns in Nevada that still bans gambling.

A POWERFUL LEGACY

The power created by Hoover Dam was instrumental in how the southwest corner of the country developed; the growth of Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and Phoenix is directly related to the availability of energy. Hoover Dam and its partner dams Davis, Parker, and Imperial, helped create the rich farmland of the Imperial and Coachella Valleys as they transformed the untamed energy of the Colorado River into a steady, usable feed. During World War II, defense plants in Southern California needed power, as did the newly built Basic Magnesium, Inc. (BMI), in Henderson, which had been contracted to create magnesium bombs. BMI eventually came to use up to one-fourth of the dam’s output. Hoover Dam’s energy output was so important to the war effort, machine gun pillboxes were built into the canyon walls in an effort to protect the structure.

Today, some 4.2 billion kilowatt hours are generated via the 17 turbines that crank ceaselessly within the dam’s immense power plant. From 1939-49, The Bureau of Reclamation allocated the power to entities in Nevada, Arizona, and California. Today, despite a drop in water levels of 20 percent in the last 15 years, six new turbines are being built. The first was installed in 2012, and the final two are expected to be completed this year—this is expected to help keep power generation up during the current drought.

BRIDGING THE GAP

While crossing over the dam is a bucket list item for many— roughly 7 million cars drive across each year—the original two-lane road quickly became inadequate for the burgeoning through traffic the route from Nevada to Arizona experienced. Citing unsafe conditions (hairpin turns, limited sight) and the potential danger to the dam itself, officials as far back as the 1960s expressed concern about the roadway.

That concern increased each year, along with tourist traffic and the number of pedestrians. Delays and congestion prompted the Federal Highway Association to find an alternate crossing, and in 2001, the Sugarloaf Mountain Alternative site was designated, just 1,500 feet south of the dam.

Construction on what would become the Mike O’Callaghan– Pat Tillman Memorial Bridge began in 2005, cost $114 million (the entire bypass project cost $240 million), and was completed in 2010. It was the first concrete-steel arch composite bridge built in the U.S., and is the longest concrete arch bridge in the U.S.

Mike O’Callaghan was Governor of Nevada from 1971-79 and Arizona Cardinal’s player Pat Tillman was killed in action in Afghanistan in 2004.

The Name Game

Until 1947, the dam was known as Boulder Dam due to its originally planned location in Boulder Canyon. It was officially dedicated Hoover Dam by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1947.

GO JUMP IN A LAKE

Stemming the tide of the Colorado River was one thing, but creating a reservoir to contain its waters was an entirely separate feat. Lake Mead is the largest reservoir in the U.S. by volume, and in its creation, at least three towns were left beneath its waters. The most notable was St. Thomas, which once sat along the Muddy River south of Overton. The Mormon settlement was once home to 500 people, but the last resident left in 1938 as the waters rose and covered the town. When the water was at its highest point, St. Thomas was 60 feet below the surface. Today, however, the town site is again visible due to the receding waters. Lake Mead was the country’s first designated national recreation area, named Boulder Dam Recreation Area in 1935; the name was changed in 1964. The park covers 1.5 million acres; 200,000 of those acres are water. In 2013—the most recent year data is available—more than 6.3 million people played in and around Lake Mead’s waters.

While the drought has lowered the lake’s levels, it’s also given rise to some new opportunities. This year the National Park Service authorized guided dive tours of the Boeing B-29 that crashed into the lake in 1948. It’s the first time in six years the dives have been allowed, due to the water level. Once-submerged caves, a concrete construction facility used in the dam’s creation, and the town of St. Thomas are also drawing visitors. The future of Hoover Dam is often debated, mostly due to the mercurial nature of western weather. And while the waters of the Colorado River are indeed a more fragile resource than the dam’s creators understood, the importance of Hoover Dam as an energy source is undeniable. It may be facing a perilous future, but the dam itself is a feat of nature and a testament to the dreams and fortitude of men.

Eerie Coincidence

On Dec. 20, 1922, J.G. Tierney, a Reclamation employee, was doing a geological survey of the Colorado River and fell from his boat and drowned. His death is not among the official numbers, because it happened eight years before construction began. However, his son Patrick Tierney is the last recorded death during construction. He died Dec. 20, 1935—13 years to the day of his father’s death.

Sign Of The Times

Thousands of workers were needed to build the dam, and while it was federally mandated that black workers be hired, less than three dozen actually were. Also, Chinese workers were forbidden to work on the project, and only a handful of American Indians were ever hired.