Nevada Part VII: To War and Beyond

September – October 2014

Plunged back into the nation’s conflicts, Nevada solidifies itself as a worldwide destination with the help of some infamous assistance.

BY RON SOODALTER

Nevada emerged from the Great Depression in 1939 with barely enough time to catch its breath before being plunged into World War II. Since the 1920s, Nevada had subscribed enthusiastically to America’s policy of isolationism. However, as the nation’s former allies were being dragged into the war, Nevadans’ attitudes began to change. Nowhere was this more evident than in Congress. Throughout the 1930s, Key Pittman—Nevada’s senior senator and chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee—had been a strong advocate of isolationism and of an arms embargo; by 1939, however, he reversed himself.

During that year’s heated congressional debate over the Neutrality Act, he strongly acknowledged that America needed to involve itself in current world affairs.

In the fall of 1940, for the first time in history, Congress instituted a peacetime draft, calling for the induction of 900,000 men between 21 and 36 years of age and stipulating a one-year term of service. A day was set aside for draft registration, and parades and rallies were held throughout the state. Patriotic fervor continued to grow, and in July 1941, Nevada’s Veterans of Foreign Wars advocated an immediate declaration of war against Germany and Italy, and an extension of the draft. The following month, Congress tacked another six months onto the length of service, and when Japan dropped its bombs four months later, Nevadans in uniform joined the rest of the nation seeking redress in battle.

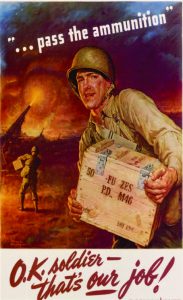

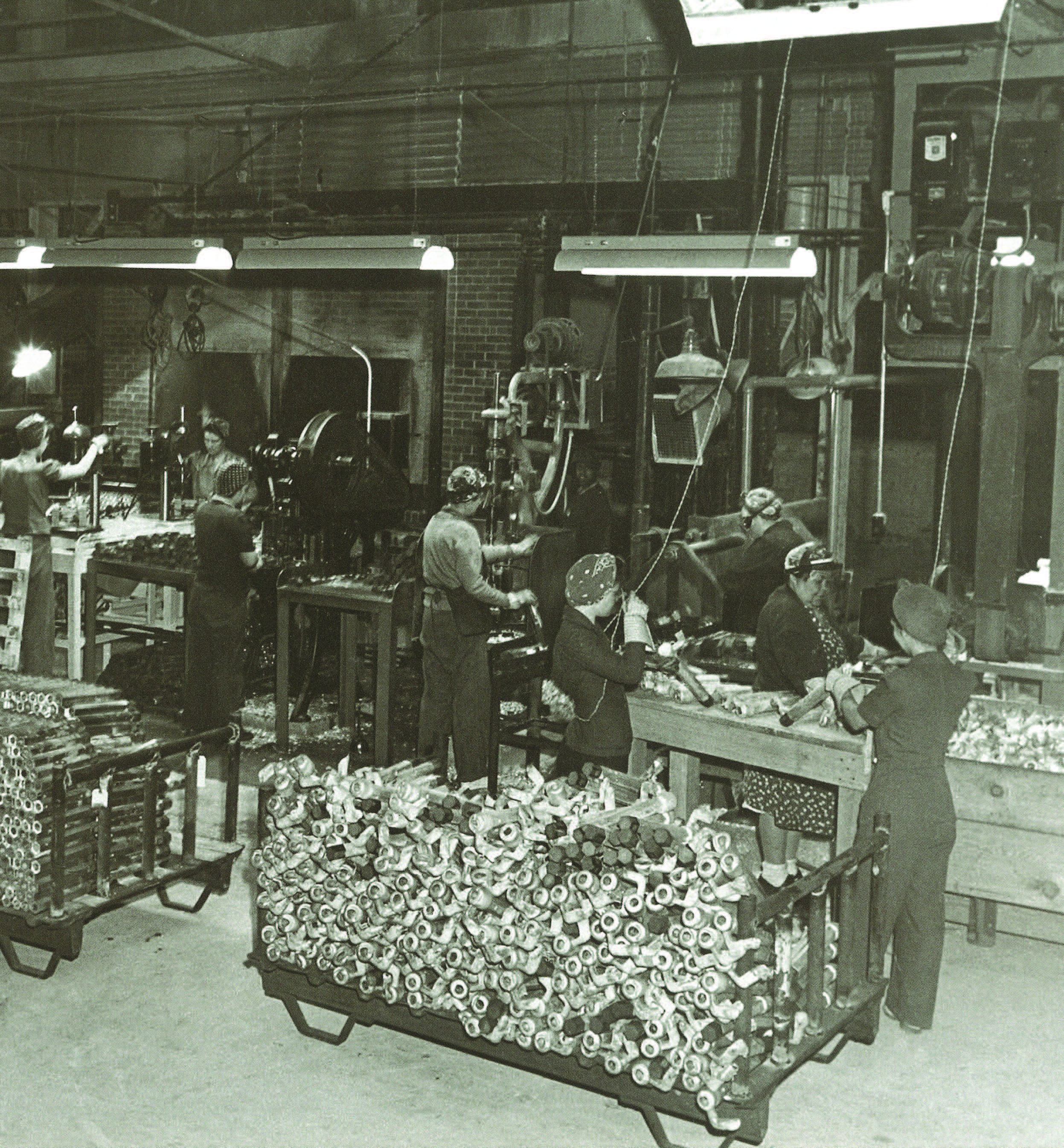

In fact, Nevada offered a great deal more to the war effort than just its soldiers. By the time the armistice was signed, Nevada had contributed as much as, if not more than, any other state to ensure victory over the Axis powers. And as it provided products, services, and labor for the war effort, Nevada benefited immeasurably.

THE MINERAL BOOM

Not surprisingly, Nevada’s mining industry played a huge role in the war, as it had in the past, providing much-needed metals in World War I. Now, copper and other minerals were being shipped to beleaguered nations in Europe and the Far East as early as 1939—two years before America’s entry into the war—and by 1940, the state’s mineral production peaked at an impressive $43,864,107. The number of jobs in the copper industry increased significantly, and the salaries of the Nevada Consolidated Copper Corporation’s employees rose with the demand. By the time Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, the mining industry of Nevada was well placed to supply its country’s mineral needs.

In mid-1940, Nevada established county defense councils to address the nation’s needs at the grassroots level. They initiated a scrap-aluminum drive throughout the state, which over the next few years was expanded to include a number of other materials. Nevadans responded enthusiastically. As historian Russell R. Elliott observed: “Schoolyards often gave the impression of junkyards rather than playgrounds as the students joined adults in the collection of scrap materials.”

In July 1941, work began near Las Vegas on a $150-billion plant—contracted by the Defense Plant Corporation—for the generation of magnesium. Basic Magnesium, Inc. (BMI), as the new plant was labeled, was a division of a Midwestern enterprise called Basic Refractories, which held crucial mineral deposits in Nye County. The contract stipulated that BMI—powered by Hoover Dam—would provide 112 million pounds of magnesium to the War Department annually. Magnesium—referred to during the war alternately as the ‘wonder metal’ and the ‘miracle metal’— was alloyed with aluminum, and used in the manufacture of airplanes, incendiary bombs, flares, and ammunition.

The plant officially opened in September 1941, just three months prior to America’s entry into the war. It created thousands of jobs and provided 25 percent of the country’s magnesium. At its height, BMI was producing some 5 million pounds of magnesium ingots per day.

The town of Henderson sprang up around the plant and thrived along with the demand for magnesium. The end of the war would signal the end of the magnesium boom, and many of Henderson’s residents soon left to find work elsewhere. But with the help of the state government, the town bounced back with a vengeance. Today, Henderson is the second largest city in Nevada.

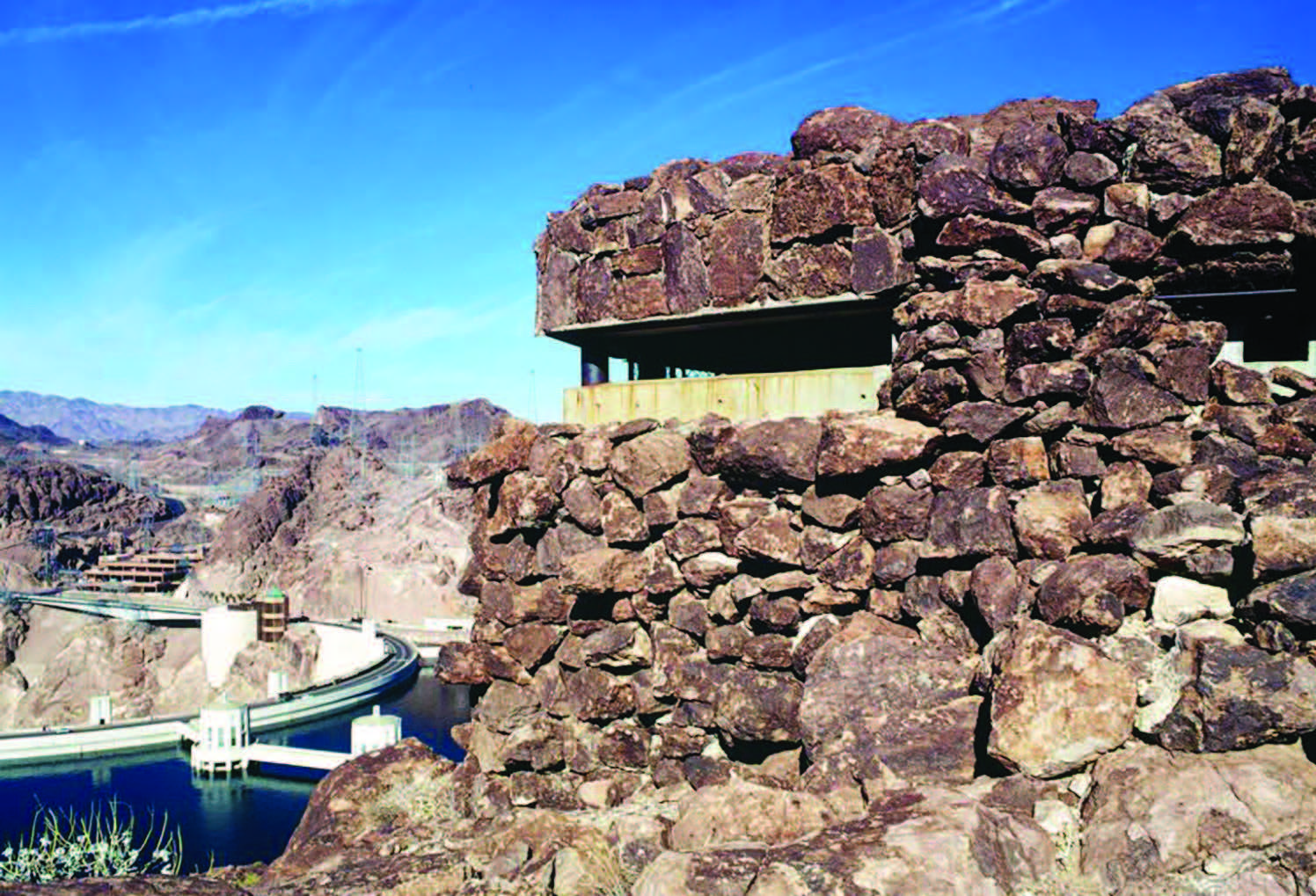

PROTECTING HOOVER DAM

The importance of protecting the highest structure of its kind in the world, and safeguarding the indispensable role it played in the war effort was not lost on the federal government. In addition to its intended functions of storing irrigation water, providing flood control, and supplying power to portions of Nevada, Arizona, and California, it also drove the Basic Magnesium plants, and various defense plants where airplanes and other armaments were being fabricated 24 hours a day.

Government agencies, however, often couldn’t decide where their responsibilities toward the dam began or ended. Files from the National Archives and Records Administration tell the fascinating story of the federal government’s generally uncoordinated and less-than-optimal efforts to protect Hoover Dam.

That the dam was a viable target for both sabotage and air attack was obvious. In 1939, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which had designed and built the dam, was assigned the virtually impossible job of protecting it. One of its first steps was to create a nine-man force of rangers, deputized as U.S. marshals, to patrol the dam. Soon after, the National Park Service was brought in to oversee activity on Lake Mead.

By this time, Adolf Hitler’s aggressive policies in Europe had many government officials on edge. The Secretary of War—who was of the opinion the dam’s employees represented the greatest potential threat—suggested to the Secretary of the Interior that employees be regularly screened, and that no one be allowed to carry parcels of any kind into the dam.

The Interior Secretary responded that his department lacked the funds for such a program.

Then on Nov. 30, 1939, the threat to Hoover Dam became real. That night, the State Department received word that the U.S. Embassy in Mexico had unearthed a plot to bomb the dam. According to intelligence, two German spies living in Las Vegas made several visits to the dam and were preparing to destroy its intake towers. Their plan was to approach their targets by boat, disguised as fishermen.

The Bureau of Reclamation immediately suspended all private boat traffic on Lake Mead and imposed severe restrictions on visitor and employee access to the dam. The Bureau beefed up its ranger staff to 39, while the National Park Service increased patrols on the lake. Floodlights were installed to illuminate the dam’s most vulnerable spots, and a huge steel mesh net was hung to prevent boats from approaching within 100 yards of the structure. The measures discouraged the saboteurs.

In January 1940, Reclamation Commissioner John Page asked Director of the FBI J. Edgar Hoover to evaluate the security of the dam and powerhouse, and make practical suggestions for its improvement. Hoover submitted a report containing 38 recommendations. Some were impractical, others unaffordable; but a number of suggestions were well-founded, including the installation of metal gates at both the Nevada and Arizona entrances to allow manned inspection stations; a training program, to be given by the FBI—for rangers and appropriate personnel; and closer scrutiny of visitors, packages, and vehicles. Ultimately, a number of the improvements were implemented, including construction of the metal gates.

In February 1940, the War Department confidentially informed Reclamation that another plot had been uncovered, and that “life and death orders have been given by Berlin to put L.A. in the black.” German agents had traveled from Havana to Miami, and then to Long Beach. “Unless quick action is taken,” warned the Secretary of War, “some terminal transformer station somewhere near Boulder Dam and another station in Los Angeles are doomed to be sabotaged.”

Although nothing came of this threat, other suspicious events occurred, including an incident in which a sniper fired at a National Park Service patrol boat, narrowly missing the ranger aboard. Again, more men were added to the ranger staff.

Meanwhile, the Interior Secretary requested that the War Department provide soldiers to conduct regular patrols at the dam. Secretary of War Harold Stimson refused, on the grounds that “it would be uneconomical and unsound to dissipate our military strength using troops, which should be training for combat…” The Reclamation commissioner then made his own bid for assistance, asking for a supply of small arms and ammunition to be assigned to the rangers. Again, the Secretary of War refused, stating all weapons would be needed by the Army.

In late 1940, the War Department announced the building of Camp Sibert at Boulder City, as a military police training encampment. Rumors ignited, claiming the 800 military police and support troops were there to safeguard the dam—rumors legitimized by several national newspapers, including the Washington Post. The War Department soon made it amply clear that the new cantonment was not there to protect Hoover Dam. Reclamation and the Army eventually did make a deal, however, whereby troops would man the new entrance gates and go on limited patrols of the switchyards and some of the outbuildings. It wasn’t ideal, but it was better than nothing.

Visitors to the dam came and went unhindered, until the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. The dam was immediately closed to visitors, and cars and staff were frequently and thoroughly inspected. Air attacks were greatly feared; consequently, airspace over the dam was restricted. Without enforcement, however, little was done to control air traffic. To Reclamation’s further frustration, the Army refused to specify how its strategy for the defense of the West Coast included protecting Hoover Dam. Tired of waiting, Reclamation explored the possibility of developing its own camouflage and smoke screens, but nothing came of the study.

Meanwhile, the Interior Secretary implored the War Department: “Because the loss of Boulder [Hoover], Parker, and Grand Coulee power plants would be a fatal blow to war production… [and] because the Department of the Interior does not have the facilities for their protection from air assault…I request that the Army assume the entire responsibility for their protection.” More than a month later, Stimson finally replied that the “threat at this time is considered to be limited to nuisance or sporadic air raids by light planes…or at most, medium bombers…under the circumstances I believe…that assumption by the Army of responsibility for…protection of the dams in question is not necessary.”

And so it went. In September 1943, the Army removed the small number of troops who had been manning the guard-posts and patrolling the outer sites. And adding insult to injury, the FBI refused Reclamation’s request to conduct another security evaluation. For the remainder of the war, the Bureau of Reclamation was left alone to safeguard one of the most vital structures in the nation. Finally, by late 1944—with an Allied victory all but certain—concern over security abated, and in August 1945, the site re-opened to visitors.

PUTTING PLANES IN THE AIR

Shortly after President Roosevelt declared war, the West Coast of the United States became what one historian described as a “great staging arena for the shipment of troops and supplies to battle stations in the Far East.” Nevada was one of the more logical choices, given its geography, available land, favorable weather, and relatively sparse population.

From the very beginning, it was clear that winning the war would depend in large measure on control of the skies. At this juncture, the Air Force was still under the aegis of the U.S. Army, and the Army desperately needed planes and men who could fly them. Starting as early as 1939, the U.S. Army Air Corps began a program of building and expanding already existing airfields in Nevada, such as a crude airfield just north of Las Vegas, which had been built 10 years earlier for use by a private airmail company. It consisted of a rough shack, a well, and a dirt runway. Dubbed McCarran Field in the mid-30s, it was bought by the city of Las Vegas in early 1941 and leased to the U.S. Army, which immediately began construction of a flight training site and a gunnery training school. Renamed the Las Vegas Army Airfield, it became operational just a few weeks after the declaration of war.

In Fallon, 60 miles east of Reno, there were two runways, each more than 5,000 feet in length. The Navy took them over in 1943 and set about establishing an installation, both for pilot training and to create a buffer against a Japanese air attack from the west. Soon, barracks, hangars, and target ranges were built, and the site was officially designated Naval Air Station Fallon.

The Stead Air Force Base, established just north of Reno in 1942, trained signal companies and eventually became a center for navigation and radio schools. Meanwhile, the Naval Ammunition Depot near Hawthorne, which had received its first shipment of high explosives back in 1930, now became the focus of major activity and growth. The depot rapidly assumed the role of staging area for most of the war effort’s bombs, rockets, and ammunition, eventually employing some 5,625 persons.

Perhaps the most jinxed of all Nevada’s bases was the huge Tonopah Army Air Field. Built in Nye County seven miles from Tonopah, it initially served as a training center for bomber and fighter squadrons—it was also the site of several fatal crashes. According to the Central Nevada Museum and Historical Society website, “It soon became apparent…that the range could not be used successfully as a fighter training area. Possibly due to Tonopah’s 6,000-foot elevation and design problems with the P-39 Airacobras, the planes and pilots were being lost in crashes at an unacceptable rate. It was decided to change the operation to a high-altitude bomber training base to train crews of the B-24 Liberators.”

Bombers crashed as well. On one day alone, in August 1944, two Liberators crashed within an hour of one another, killing all 18 crewmen. The number of dead airmen continued to climb: the Historical Society website lists the names of 110 men killed in crashes at Tonopah, adding, “There are undoubtedly other names which were not listed in these sources.” Since the list was first compiled, another 30 names of Tonopah’s crash victims have been discovered, and the search continues.

Crashes and setbacks notwithstanding, Nevada’s military installations built many of the nation’s weapons and trained countless young men in their operation. In the process, the population of the communities near the various bases swelled, with predictably positive results.

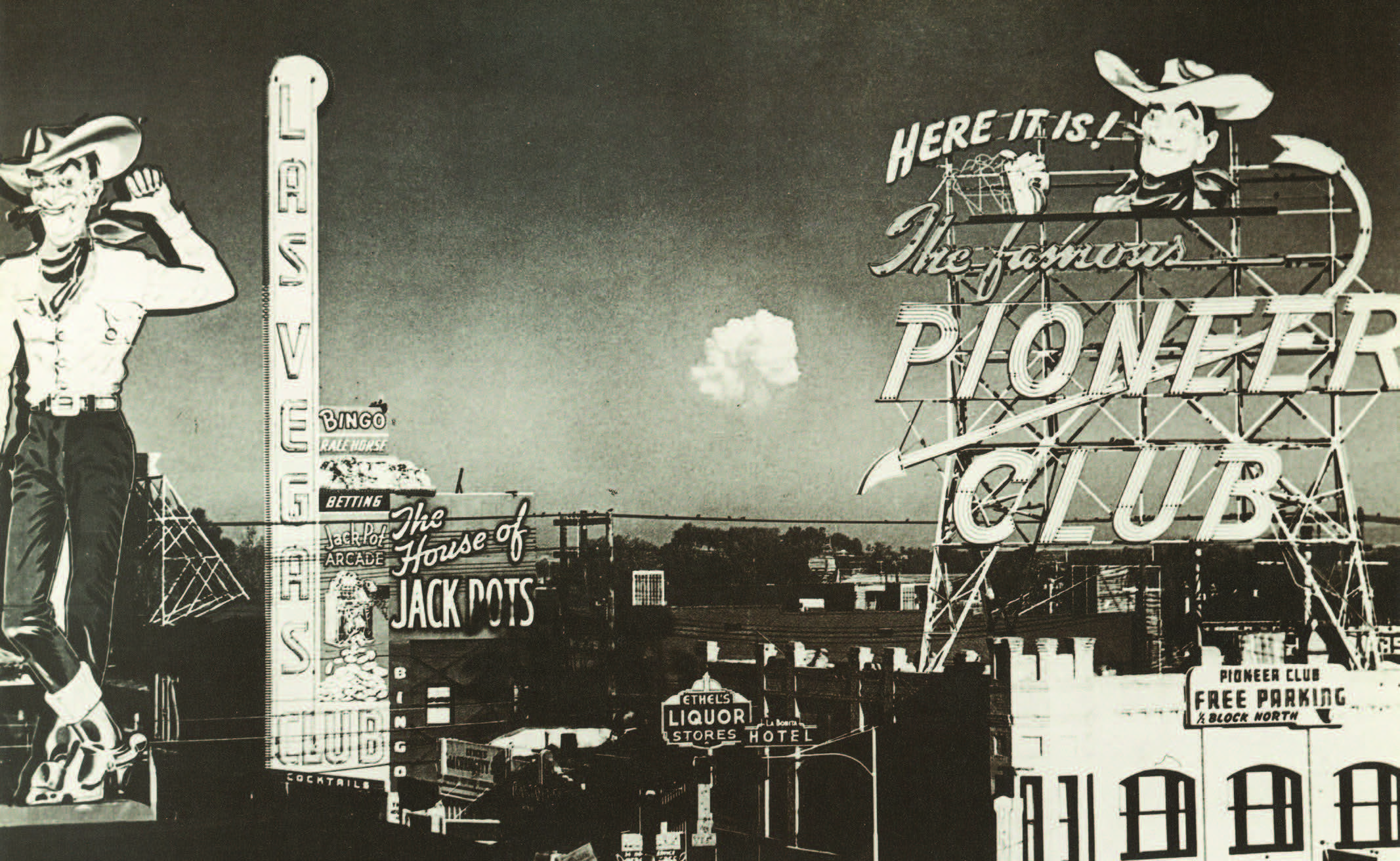

AN AMUSEMENT BOOM

With the many thousands of military and civilian personnel required to operate the new military bases, the economy of nearby towns and cities soared. Heretofore modestly sized communities such as Ely and Elko suddenly saw themselves inundated by soldiers on leave, desperate to take their minds off the daily grind of training and the realities of war. For Las Vegas and Reno, already well established as “amusement centers,” it signified a boom the likes of which their citizens had never seen. Gambling and prostitution were legal—the latter only in some counties—and liquor was readily available—all within a short distance of some bases. Civilians who had come to Nevada for steady work at the state’s defense plants added to the growing number of patrons. And when soldiers in California got wind of the delights available just across the state line, they too began to frequent Nevada’s gambling parlors and bordellos.

Finally, the federal government had enough—at least of Nevada’s prostitution laws. Concerned over what its directors perceived as a lapse in morality, the Federal Security Agency prevailed upon local officials to board up the brothels. While some may have believed that this ended large-scale prostitution in the state, the industry merely changed venue, plying its trade in hotel rooms and boarding houses run by liberal and profit-minded managers and landlords.

Another effect of the military presence was a staggering growth in population, mainly for Reno and Las Vegas. In the 10 years beginning in 1940, the population of Las Vegas grew from 8,422 to 24,624—a stunning increase of nearly 200 percent. For its part, Reno increased by more than 50 percent, as Nevada’s overall population demographic went from largely rural to increasingly urban.

As gambling continued to draw visitors by the thousands to Reno and Vegas—although practically every community in the state offered it by now—it was Elko that came up with a formula that would forever alter the way Nevada attracts visitors. The idea, hatched in 1941 by hotel owner and native Nevadan Newton Crumley, Jr., was to hire the biggest entertainers of the day to perform for patrons. Crumley correctly reasoned that even inveterate gamblers would enjoy some time away from the tables and he planned to offer the best entertainment money could buy—and in the process, attract more gamblers to his Commercial Hotel.

The plan paid off in spades. Crumley’s first coup was to book the world-famous Ted Lewis Orchestra for eight days.

Although he paid the stunning fee of $12,000, he was rewarded with standing room-only crowds and a significant hike in gambling revenues. Soon after, he engaged such stars as the Dorsey Brothers, Lawrence Welk, Sophie Tucker, the Andrews Sisters, and Paul Whiteman. It couldn’t get any better.

It didn’t take the casino owners in Reno and Las Vegas long to get the message, and they soon followed suit, reclaiming their positions as the state’s primary attractions. Nevada soon added “entertainment hub” to its list of attractions, and tourist travel to the state increased dramatically. By the end of the war, with such clubs as the Frontier, the Golden Nugget, and the Mint running around the clock, Las Vegas established itself as the center of Nevada’s tourist business.

As gambling continued to become big business, the State Tax Commission enriched Nevada’s coffers by levying a 1 percent tax on all gambling. In 1947, the state legislature raised the tax to 2 percent, and added table fees to the mix. In 1949-1950, the state’s take from gambling taxes and table fees reached an impressive $1,211,194. By this time, however, another presence existed on the Las Vegas gambling scene: organized crime.

ENTER THE MOB

If we believe the movies, Las Vegas in the late 1940s was a sleepy little cowboy town, with a slot machine or two in a local bar—that is, until a handsome New York psychopath named Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel appeared on the scene. Envisioning a gambling oasis in the desert, he created the Flamingo, a fabulous hotel and casino.

In fact, Las Vegas was doing very well with nationally known casinos and big-name entertainment, long before Mr. Siegel and his cronies arrived. The Flamingo was not even Siegel’s idea; it was the brainchild of a Hollywood nightclub owner named William Wilkerson. Siegel merely acquired the unfinished Flamingo—with Mob backing—when Wilkerson ran out of funds.

The Mob had had a presence in Las Vegas for years, but it was limited. As early as 1942, Siegel had come to the area to gain control of the Las Vegas racing wire services. What Siegel, along with his fellow thug Meyer Lansky, managed to accomplish with his expensive—and ultimately fatal—development of the Flamingo in 1946 was the involvement of the Mob as club and hotel owners. And once they attained a foothold, the rest was history. In short order, they controlled every aspect of Las Vegas nightlife.

By the early 1950s, the involvement of organized crime in Las Vegas had become so egregious that the Senate convened a committee, under Estes Kefauver, to investigate the situation. Concluding that the Mob did indeed control much of the city, the Senate proposed a measure providing for federal control of gambling. The measure was defeated in large part due to the efforts of Nevada’s powerful Senator Pat McCarran. While there is no actual documentation, a number of chroniclers have posited that the corrupt Senator Geary of “The Godfather” films was based on McCarran.

Through the early-to-mid 50s—using “clean” money and often fronted by legitimate businesses and banking institutions—the Mob built or assumed control of a number of high-end casinos and hotels, including the Sahara, the Sands, the Riviera, the New Frontier, and the Tropicana. The practice of bringing in big-name entertainers continued, and by the late 50s and early 60s, patrons could enjoy gourmet food and the finest wines while attending shows by such world-class celebrities as Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., and Dean Martin, as well as Elvis Presley, Bing Crosby, Carroll Channing, and Liberace. Hundreds of millions of dollars a year were being funneled through Vegas’s casinos and hotels. Gambling had become Nevada’s largest commercial enterprise; it now remained for the state to regain control of its regulation.

TESTING MASS DESTRUCTION

Another economic boon, albeit of a more devastating nature, came to Nevada after the war. The federal government consistently allocated financial aid and job-creating projects to the state since the Great Depression, but it outdid itself in December 1950. The U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) chose Frenchman Flat, just 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas, as the site of the Nevada Proving Grounds—the primary installation in the United States for testing nuclear bombs. The Cold War was ramping up, citizens were terrified of a nuclear attack, and all the stops were pulled out in the quest for the perfect weapon.

More than a century before, the test site’s community of Mercury was a tiny oasis for mercury miners and desert rats. “There,” wrote one chronicler, “the local miners gathered…to indulge in drink and an occasional bath, and a brief escape from the rigors of the desert heat.” Due to the highly sensitive nature of the AEC’s work, Mercury became a closed town, its workers a far cry from the hard-rock miners who peopled the Comstock, or the raw-boned towns of Goldfield and Tonopah. Historian Elliott described the site as a “boom camp, whose inhabitants are trained workmen, engineers, and scientists, working with the most sophisticated equipment yet produced.”

In January 1951—less than one month after the test site was established—the first nuclear bomb was dropped on the nearly 1,400-square-mile testing ground. That test was the first nuclear explosion to be televised. The flash was seen as far away as San Francisco.

Initially, the tests were conducted above ground. The government arbitrarily established a 125-mile perimeter as the distance from communities at which nuclear bombs could be safely detonated, ignoring the fact that Las Vegas lay well within the boundaries of this “safety zone.”

According to Online Nevada Encyclopedia, testing expanded to include other nearby locations. “Nuclear weapons tests occurred in four regions within the Test Site: Frenchman Flat, Yucca Flat, Rainier Mesa, and Pahute Mesa. Three types of tests were conducted: weapons effects, weapons design, and tests involving the military who conducted operations near ground zero for the purpose of developing battleground tactics and strategies.”

One of the tests involved monitoring the effects on humans. To this end, the government stationed unprotected ground troops as close as 2,500 yards from the detonation, and then moved them closer after the blast. Predictably, the tests resulted in inordinately high numbers of cancer cases among the soldiers and members of the local communities.

At first, the mushroom-shaped clouds of the detonations fascinated the public, and many of the early tests—which were visible from as far away as Las Vegas—had an outdoor audience. For years, people either didn’t realize, or chose to ignore, the potential dangers of fallout from above-ground or “atmospheric” nuclear testing, and downwind communities suffered a massive increase in various forms of cancer.

By 1957, the effects of radiation were undeniable, and atmospheric testing was gradually discontinued. Beginning in late 1962, the government finally responded to international pressure, and moved all nuclear detonations underground. However, underground testing caused its own concerns. Very real fears were raised over possible seismic events and potential contamination of water sources. In September 1992, the federal government called a halt to all underground detonations as well.

By this time, some 1,021 nuclear detonations had taken place at the site, the great majority of them underground. It is still however, a very active site. According to the University of Nevada, Las Vegas’ Oral History Program, “Subcritical [nonnuclear] tests and other forms of national security programs are still conducted at the Nevada Test Site.”

On the plus side, the placement of the Proving Grounds in Nevada resulted in an ongoing boost to the state’s economy.

In 1956, Nevada’s employment rolls and revenues were further enhanced when the federal government chose the test site for the building of nuclear reactor engines for NASA. These were used in spacecraft and as rocket propellants well into the late 1970s, when the space program fell on slack times.

BOOM AND BUST…YET AGAIN

For the third time, a major war involving the United States created a boom in Nevada’s mining industry. Demand for the state’s minerals, primarily copper, had caused production to soar, swelling the ranks of employees and raising salaries. When the war ended in 1945, there was little reason to think that things would change for the worse—unless, of course, one was a student of history. No single mining strike in Nevada’s history survived into the modern age. As one chronicler put it, the “rude, dusty towns” of the early days “soon collapsed into ghostly ruins.”

Nonetheless, despite a brief downturn, Nevada’s mineral production achieved record levels, thanks to the demand generated by the Korean War. From 1950 to 1975, copper once again dominated the scene. It was responsible for half the state’s mineral output. Fresh deposits of copper were found, and it was being mined in new sites as well as the old. Meanwhile, additional minerals were mined and processed as well: tungsten, iron ore, and mercury. And for the first time, Nevada became an oil-producing state in 1954, albeit on a minor scale, with Shell Oil’s drilling of a well— Eagle Springs No. 1-35—in Nye County, 50 miles southwest of Ely.

After a drop-off following the Korean War, copper production picked up again with the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. It appeared that as long as America went to war, there was money to be made from Nevada’s mineral deposits.

In 1965, one of the first large open-pit gold mines was developed near Carlin. It was followed in 1969 by another in the Cortez mining district 60 miles to the southwest. After an absence of many years, Nevada had again become one of the country’s major gold producers.

That same year, a third copper-rich area was being developed in the aptly named Copper Canyon, south of Battle Mountain. However, by the middle of the next decade—despite the fact that it entered the 1970s still leading in Nevada’s mineral production—copper was dying a swift death, as demand virtually disappeared. The year 1977 saw the closing of the Victoria mine, followed the next year by Weed Heights and Battle Mountain. By decade’s end, copper production in the state was virtually over, after a reign of more than 60 years as Nevada’s leading mineral. Still, Nevada managed to maintain production of a number of other minerals. Gypsum was being extracted from Arden, Apex, and Gerlach, while barite mines were being worked in Lander, Elko, and Nye counties. And the state was still producing serious amounts of diatomite, borax, sand, gravel, limestone, silica, fluorspar, and perlite.

By the end of the 1970s, encouraged by a new high in worldwide metal prices, Nevadans were predicting a boom to surpass those of Tonopah, Goldfield, and the Comstock. But mining trends were anything but predictable, and once again, the Silver State would be given a bitter lesson in the true meaning of “boom and bust.”

Read the Entire 8-Part Series

Part I: The Unknown Territory

Part II: From Strikes to Statehood

Part III: Twain, Trains, & The Pony Express

Part IV: Into the New Century

Part V: War, Whiskey, and Wild Times!

Part VI: Gambling, Gold and Government Projects

Part VII: To War and Beyond

Part VIII: Looking Forward, Looking Back