Odyssey of a Ghost Town Explorer part 12

November – December 2019

God’s own country

BY ERIC CACHINERO

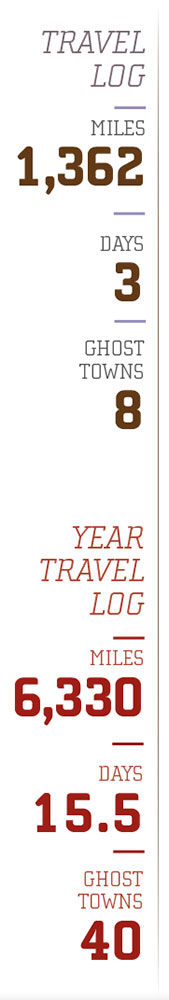

12,084 miles. That figure is just a bit shorter than half the circumference of the Earth. It is also the distance I have driven in 2016 and 2019, entirely within the state of Nevada, searching for ghost towns.

I’ve spent nearly 300 hours in the car and used 700 gallons of gas to seek out more than 70 ghost towns. I’ve drank 36 cups of coffee, eaten 36 breakfast burritos, and spent 36 days on the road. I’ve encountered at least 3 flat tires, and many more migraines as a result. I’ve explored ghost towns in weather that fell well below 32 degrees, and well above 105. I’ve written roughly 26,500 words about these places in 12 different issues of Nevada Magazine, equating to about 2.2 words per mile. I’ve seen thousands of deer, hundreds of antelope, dozens of elk, and a couple trout. I’ve seen billions of sagebrush and stars.

I’ve gazed across infinite miles of this great state; God’s own country.

BEYOND THE PINES

Rain is in the forecast and gaudy pop music is on the radio as Editor Megg Mueller and I make our easterly way across Interstate 80 toward Wells. Our crosshairs are on Sprucemont mining district, located on the southwestern tip of the Pequop Mountains in eastern Nevada. Luckily for us, the rain is intermittent and weak, and the mining district is easy to find.

The Sprucemont district was formed when ore was discovered and the Latham Mine was constructed in 1869. Located at around 8,500 feet, mines were dug next to spruce and pine trees—an unusual setting for a typical Nevada boomtown. As ore production ramped up and a town began forming, prospectors widened their scope and discovered just about the entire northeastern side of Spruce Mountain contained ore. This widespread discovery gave rise to several mines located in close quarters, including the Standard Mine, Ada H Mine, Kille Mine, Black Forest Mine, and Monarch Mine. Along with saloons, butcher shop, post office, and a blacksmith shop, a smelter was constructed by 1871 to handle ore coming from the mines. Not long after, though, the smelter could not process the district’s lead-silver ore in a profitable manner. Ore production faltered for several years, and during the next several decades, attempts were made to revive the district, albeit unsuccessfully. In 1930, the camp saw new life, and would remain producing ore through World War II, though profits were scant and production would soon fade altogether.

The Sprucemont district was formed when ore was discovered and the Latham Mine was constructed in 1869. Located at around 8,500 feet, mines were dug next to spruce and pine trees—an unusual setting for a typical Nevada boomtown. As ore production ramped up and a town began forming, prospectors widened their scope and discovered just about the entire northeastern side of Spruce Mountain contained ore. This widespread discovery gave rise to several mines located in close quarters, including the Standard Mine, Ada H Mine, Kille Mine, Black Forest Mine, and Monarch Mine. Along with saloons, butcher shop, post office, and a blacksmith shop, a smelter was constructed by 1871 to handle ore coming from the mines. Not long after, though, the smelter could not process the district’s lead-silver ore in a profitable manner. Ore production faltered for several years, and during the next several decades, attempts were made to revive the district, albeit unsuccessfully. In 1930, the camp saw new life, and would remain producing ore through World War II, though profits were scant and production would soon fade altogether.

The Sprucemont district is a ghost town gold mine. Megg and I first explore the remains at the Standard Mine, which include a series of remarkable stone walls, before driving further up the canyon toward the Ada H Mine.

The remains at Ada H include some decrepit wooden shacks, which we poke our heads in before the intoxicating beauty of the canyon lures us higher and higher into the mountains. It’s like we’re playing hide and seek with these historic structures. As we continue on, the road becomes steeper and more treacherous, but the historical offerings continue to reveal themselves, so higher we go.

We soon arrive at the apex of our climb—the Kille Mine. Exploratory tailing piles dot the hills like a series of oddly placed sandboxes, though the main mine isn’t hard to mistake. The massive horizontal gash in the Earth appears as if it was caused by the ground simply opening up and swallowing itself whole. I stand on the edge of the pit and day dream that a set of jagged teeth and tentacles reveal themselves, and I’ll be face to face with the Sarlacc pit, as Luke Skywalker was in the famous “Star Wars Return of the Jedi” film, with Jabba the Hut cheering my inevitable demise.

Unluckily for Jabba the Hut, that doesn’t happen, and we continue on and begin to descend the eastern side of Spruce Mountain, where the road turns nasty. This is offset by the impeccable beauty of the area, though, which is rich with evergreen vegetation (and strangely looks like the “Star Wars” forest moon Endor). We decide to drive down one final steep section before turning around, which turns out to be a good idea, because we reach the Black Forest Mine, and the immensity of ghost town real estate that remains there.

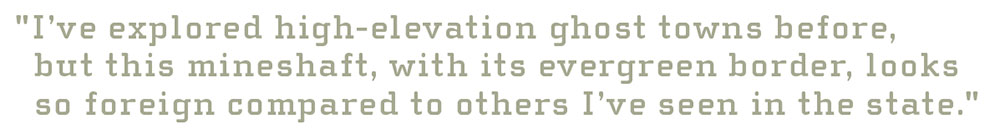

There’s a bunch of cool old machinery and buildings at Black Forest to explore, but my favorite feature is the mineshaft that descends horizontally into the mountain. I’ve explored high-elevation ghost towns before, but this mineshaft, with its evergreen border, looks so foreign compared to others I’ve seen in the state.

We finish up at Black Forest and climb the steep hill back over toward our final mine of the day—the Monarch Mine. As we drive, we’re treated to a world-class Nevada sunset, and manage to reach the final mine just as the sun retires for the night. We stand in stillness watching the light fade from the glowing buildings, enjoying the perfect calm; a truly tranquil moment; the kind of silence that makes your ears ring.

We head to Wells for the night, with another busy day of exploring on the horizon.

AZURE

The following morning, we depart Wells and aim toward State Route 226 north of Elko. We pass the Taylor Canyon Resort—a great rural watering hole and haven for hunters—before driving toward Jack Creek, located on the north end of the Independence Mountain Range. We pause there briefly to enjoy the scenery and solitude.

The region is somewhat lacking in ghost towns, but it makes up for it in beauty. Ranch fields are filled with antelope, creeks run down every other canyon, and clusters of aspen splash across the hills. We drive north on Maggie Summit Road before we reach our first ghost town of the day—Aura.

The townsite at Aura was plated in March 1906 after a nearby gold discovery. By 1907, the town had stores, saloon, post office, school, homes, and the “Concentrator” newspaper. Aura acted as the supply point for nearby mines, though it quickly faded as the ore ran dry.

There isn’t anything left at Aura except one medium-sized stone building with a missing roof. It’s relatively unimpressive, but the surrounding views are incredible. Megg and I snap a few photos before continuing over Maggie Summit until we hit pavement again.

Once we connect with State Route 225, we head south, and because we’re on our “lunch break,” we manage to do a little bit of fishing on the Owyhee River. The river flow is fast considering we’re in the heat of summer, but that doesn’t put a damper on our day. Megg and I tie on our flies, and each pick a spot along the bank. Within a couple roll casts, I find myself with a shimmering rainbow trout on the other end of my line.

We fish for a bit longer before it’s time to punch the time clock yet again and continue north to seek out more ghost towns. The next destination on the list is Rio Tinto.

Rio Tinto is, unfortunately, a major bust. Private property signs send a clear warning, so we retrace our steps back out to the highway and head north through Mountain City, and eventually all the way to Owyhee, located right on the Nevada-Idaho border. From there we head southwest, along the western flank of the Bull Run Mountains. The ghost towns are pretty much nonexistent, but the drive is pleasant and the views are spectacular.

As the sun begins to fade, we make the long drive back to Elko, where the famous Basque cuisine at The Star Hotel awaits (see page 24).

NIRVANA

NIRVANA

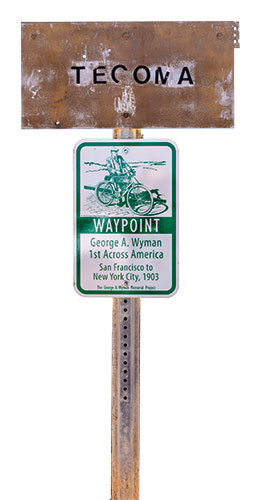

I’m proud to say that there are very few roads in this state that I haven’t driven, and today, I check State Route 233 off that list. Megg and I head north toward the small town of Montello, where we explore for a bit, then drive to our first ghost town of the day—Tecoma. A solitary faded sign lets us know we’ve reached the site.

Tecoma was founded, some sources claim, by the Central Pacific Railroad in 1869. By the early 1870s, the town had grown to about 100 residents, and had many of the amenities of a frontier town. It acted mainly as a train shipping and maintenance stop, though by the 1920s and ‘30s, nearby Montello would take over as the train stop, and Tecoma became abandoned.

More interesting than the town’s history, is its involvement in unique feats of intercontinental travel. The site was not only located along the transcontinental railroad route, but also was visited by a man by the name of George A. Wyman. In 1903, Wyman became the first person to make a transcontinental crossing of the United States by motorized vehicle. More impressively, he made the trip on his 1902 California Motorcycle Company motorized bicycle. The motorcycle had a 200-cc engine that ran off 30-octane gasoline (modern cars typically use 87-octane), wooden rims, a leather-belt drive, used a standard steel bicycle frame, and could travel up to 25 mph. Wyman made the trip from San Francisco to New York City in 51 days. He carried a surprisingly small amount of gear, including warm clothes, water bottle, spare oil and gasoline, a Kodak Vest Pocket camera, tools, and a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver. Given that Wyman rode a majority of this distance either on or next to the railroad tracks, his visit to Tecoma makes sense.

PROMISED LAND

No trip would be complete without Megg and I careening miles and miles into the desert unknown, chasing ghost towns we’re not even sure exist, and this one is no exception. After driving back to Montello, we head north toward the ghost town of Delano, which is at the end of about 36 miles of dirt road. The area is scenic, though unfortunately, most of the property is privately owned by area ranchers.

The drive is slow-going, both due to varying road conditions and the fact that we continuously have to stop to allow dozens of dopey bovines to move out of the path of our vehicle.

We finally make our way to where we believe Delano to be, and besides finding a large rusted water tank, there’s nothing… This is especially frustrating because of how far we traveled to get here, and how intensely remote the area is. Just as we’re about to give up, though, we spot a couple mine remnants on a distant hill, so we decide to chase after them. As we’re driving and hiking in the area, we luckily spot the remnants of Delano, and breathe a sigh of relief that the travel wasn’t all for nothing.

In spring 1872, a Native American showed prospectors an ore discovery in the area that would become Delano, and the rush was on. Though some big investing companies showed interest in many of Delano’s mines, nothing of much value was ever recovered, and the town produced just enough ore to keep it running through the decades. At times, the only business operating in Delano was the saloon. From 1920-1960, the town held a population of between 30-50, though production and population would completely fade before the decade ended. In the 1990s, most of the ghost town’s numerous wooden structures were destroyed and lost forever to a wildfire.

We find a surviving steel headframe and the Delano mineshaft, which are both spectacular artifacts. The headframe is still in great condition, while the mineshaft descends into the earth at a 45-degree angle; its opening reinforced by a massive metal cylinder. Peeking down into the mineshaft makes me equally excited and nauseous. It is a place a person definitely wouldn’t want to accidentally fall in to.

After a bit more exploration, we set our sights on home, and begin to make the long drive back to northwestern Nevada. We’re treated to another spectacular Nevada sunset as we drive, and are lucky enough to see the final fleeting pastels fade from the sky.

EDEN

The Jack Creek and Maggie Summit area that I visited on the second day of this trip is a tempest of memories for me. It is where my family used to hunt when I was a child. It is where I harvested my first deer. It is where some of my earliest remembrances came from. It’s where I was taught my love for nature and the outdoors. It is where my mind travels when I think of the most magnificent place in the world. It is where my memories of my grandfather live.

When I started this ghost town series in 2016, my grandfather Paul Earl McKee Jr. joined me on the first trip. He sat next to me as we began the very first mile; a solitary mile in a journey that would turn into 12,054 of them. Surely neither of us could have known at the time the odyssey that would manifest.

I lost my grandfather to cancer on March 16, 2018.

As painful as the memory is, it seems appropriate to end this journey in his name; to put the final mile to rest with the same passion as the first began. Much of this journey can be attributed to him, and the beauty he saw in the world.

I’ve written before that ghost towns are just an excuse to get out and explore the natural beauty of Nevada, and this fact reigns truer than ever. Ghost towns are incredible skeletons of history, but most of my memories during these past couple years are not what I found in the towns themselves, but what I experienced while getting there.

I’ll end this odyssey with one of my grandfather’s favorite quotes. I think it’s fitting, because this journey—while it hasn’t been easy—has shown me a mountain of grace, a whole lot of art, and even a trout or two.

This is God’s own country.