Railroading Sisters

May – June 2018

Two women run the U.S. Gypsum short line north of Reno

STORY BY LINDA NIEMANN

PHOTOS BY SHIRLY BURMAN

(This story originally appeared in our March/April 1992 issue)

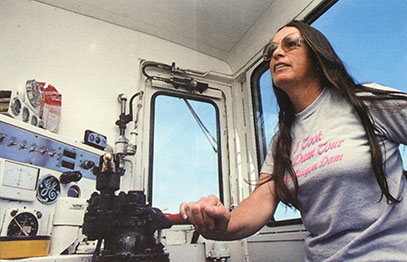

Just how rare is it for two petite grandmothers to be running a train? It’s about as common as hen’s teeth, talking pigs, or shy politicians. Shutterbugs and rail buffs stalk ing the picturesque in Gerlach and Empire get a welcome surprise when a blue-and-white switch engine appears out of the Smoke Creek Desert. The engine is run by two sisters, Barbara Clark and Linda Minto, who serve as the engineer and brakeman on the U.S. Gypsum mine’s short line.

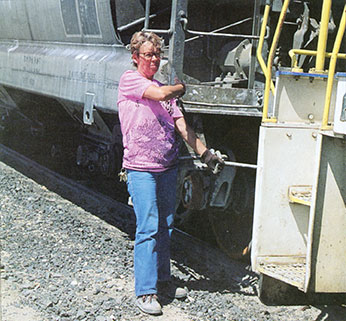

Another reason is the work itself. Railroad equipment is huge, dirty, and dangerous. Just one piece of a coupler weighs about 85 pounds, and brakemen routinely have to realign them by hand when hooking cars together. The switches are stiff and rusty, and a woman may lack the weight to wrestle them over.One reason is tradition. Railroad men would take their sons down to the yard and get them hired on while their daughters stayed at home.

So, why would a woman want to do this work? For 46-year-old Barbara, the answer was simple: A brakeman’s job was open when she hired on at the Empire mine. Her sister, Linda, 44, already worked at the mill. Linda loved living in the small company town five miles south of Gerlach and 90 miles north of Reno. Barbara, just divorced and with two small children to support, decided she wanted to live and work there, too.

“The brakeman’s job came open because the guy that had it before me shot himself in the thumb,” Barbara says. It also helped that U.S. Gypsum didn’t have rigid hiring practices, and people moved from job to job within the operation.

“I found out that if I have to, I can do anything,” she says.

“I always had somebody else to fall back on, until I came out here,” she says. “So when they told me I was going to be working on the train, it scared me to death, but I really needed a job, and I thought, ‘I’ve got to do it.”‘

Her sister, Linda, who moved to the engineer’s job when Barbara temporarily left it for a more secure position in the mill, had an easier transition to railroading.

“I worked on a drill rig once, so I was around heavy equipment before,” Linda says. “Still, it was different, at first scary.”

A typical day at work starts with Linda and Barbara donning hard hats and starting up the switch engine on a track at the mill. The railroad cars have been loaded overnight, and the sisters’ job is to hook them together and pull them down the five-mile track to the siding at Gerlach.

One of the women works on the ground hooking the cars together, untying the huge wheel brakes and throwing the switches that let them onto different tracks. The other runs the engine and follows the hand signals of the one on the ground. They trade jobs every other day.

The sisters bring snacks to eat on the engine, which resembles a room in a college dorm. On the long pull down to Gerlach at 10 miles per hour, anything can happen-snowball fights, water fights, even getting buzzed by supervisors in low-flying planes.

“At first it scared me,” Barbara says of the buzzing bosses. “But now I just wave. Sometimes you’re almost eye-to-eye with them. They’re devils sometimes, those bosses.”

At Gerlach, the women leave the loaded cars for the through freights on the Union Pacific line and pick up the empties to take back to the plant. One of the switches is difficult, and Barbara applies a length of pipe to the switch handle to give herself more leverage. As a five-foot-two, 118-pound brakeman, she has to outsmart rather than overpower the equipment. But that characteristic, the company has found, makes women easier on machinery.

Their good safety records testify to their carefulness, and both women are aware of the heavy responsfbility of running an engine in and out of a working plant. A loud buzzer sounds whenever the engine is switching inside the mill, and Barbara remembers how it came to be installed.

“I almost hit the plant manager once when he came around the corner there. He saw me, and he about had heart failure. Then he wanted me to start carrying a foghorn. That’s when they put the big buzzers in.”

Linda nods. “Now they got them honkers all over the place.”

The sisters grew up north of Reno in Susanville, California. Linda was the first to move to Empire, primarily because she loved small-town life, and Susanville was getting too big.

Empire, population 350, is a patch of greenery beside the vast playa of the Black Rock Desert. It boasts a free ninehole golf course, tennis courts, a swimming pool, elementary school, post office, three churches, and a general store. The houses and apartments are subsidized by the company. They have lawns and sidewalks shaded by cottonwood trees. Children can play safely on their own block.

Entertainment in Empire is homemade. The nearest town is Gerlach, which itself is a tiny dot on the road to nowhere. “We might go out to dinner or play the nickel ‘slot machines,” Barbara says.

Linda is a rock hound and likes to go four-wheeling with her husband. “You get up on top of one of these mountains, it’s beautiful,” she says. “You look out over the country and you can see everything.”

Giving it the appearance of a space station, tiny Empire is surrounded by endless desert. The desert acts as a kind of art gallery as the light paints the scenery differently every hour of the day.

Artists, photographers, landsailors, and others hold events on the Black Rock, finding it the perfect stage set. The locals use it more as a natural library or a church. When Barbara and Linda get time off, they rarely leave the area. Instead, they go a little deeper into what surrounds them daily. Humor, cooperation, and a sense of belonging to a family are a big part of what they like about their workplace and the reasons they have chosen small-town life.

When they retire, both Barbara and Linda plan to buy property and move to Gerlach. Until then they’ll continue to build the legacy of Empire’s railroading sisters.

Linda Niemann of Santa Cruz, California, is a brakeman-conductor on the Southern Pacific who has a doctorate in English. Her book Boomer: Railroad Memoirs was recently published by the University of California Press.

Editor’s note: The town of Empire was shut down in 2011, when U.S. Gypsum closed the mine. In 2016, Empire Mining Company purchased the town and as of today, there are a handful of residents living in Empire.