W.J. Forbes: Death, Taxes, & BM

May – June 2018

Mysterious Nevada newspaperman was nearly forgotten by the history books.

BY ERIC CACHINERO

Semblins.

While on a lunchtime jaunt at the Nevada State Museum in Carson City, I still remember how anxious I was seeing the name for the first time in my life. It was like a tractor beam defiling my focus and leaving me slightly embarrassed as I read the following plaque:

While on a lunchtime jaunt at the Nevada State Museum in Carson City, I still remember how anxious I was seeing the name for the first time in my life. It was like a tractor beam defiling my focus and leaving me slightly embarrassed as I read the following plaque:

“Though often outrageous stories, sometimes believed as fact by eastern readers, they gained and cultivated an often infamous reputation for their nom de plumes of Semblins, Dan DeQuille and Mark Twain.”

“Who the heck is Semblins?” I asked myself. “What Nevada writer could be so prestigious that his name precedes that of the fabled DeQuille and Twain in a list of three, and how in the world have I never heard of him?”

The question engulfed my curiosity and simultaneously seared my ego. Who was this character that so serendipitously usurped the names of some of Nevada’s best-known writers? How have I never heard of him? Who was this man of mystery?

Time to hit the history books.

MYSTERY MAN

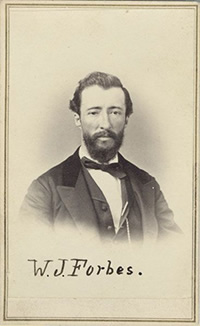

Semblins, as it turns out, is the nom de plume for a Nevada newspaperman by the name of W.J. Forbes. History seems to have forgotten his birthday, from what I can tell. In fact, history also seems to have forgotten where he is from, when he came to Nevada, and pretty much every other detail about his early life.

Forbes was a bit of a newspaper vagabond throughout his life, personally publishing and editing around a dozen newspapers in California and Nevada. Prior to his Nevada connection, Forbes dabbled in California newspapers “Coloma Argus,” “Marysville Herald,” “The Sierra Democrat,” and “Downieville.”

The “Humboldt Register” of Unionville and Winnemucca—a weekly publication printed from 1863-1876 and sometimes referred to as the “Humboldt Register and Workingman’s Advocate”—was Forbes’ first Nevada newspaper. He soon purchased the “Daily Union” in Virginia City and quickly changed its name to “The Trespass.” Forbes’ reasoning for this was that he felt he was trespassing on a previously occupied field.

Forbes also had a brief newspaper stint in 1873 in Salt Lake, where he started the “New Endowment.” In hindsight, he realized that there were no profits to be made by publishing a gentile newspaper in a Mormon community. He closed the paper with the following words: “We cease publication because we did not bring enough money with us.”

Like many Nevada newspapermen—both historic and modern—whiskey-fueled his writing career and writing fueled his whiskey career. When the newspaper business was in bad shape, he decided to follow the money, though only briefly. He remarked editorially in one of his White Pine County newspapers that, “of twenty men, nineteen patronized the saloon and one the newspaper.” So, he tried his luck in the saloon business, believed to be the only profitable business he ever ran. But soon after he started turning a profit, the sweet temptress that is Nevada journalism lured him back to the printing press, and he closed his saloon.

TOO GREAT A WEIGHT

Forbes bore the weight of his own intellect. In a world of gruff miners and seedy Wild West gunslingers, he slung his intellect, which was often more destructive than bullets. He had a hard time keeping a newspaper in business, simply because his style of writing was too smart for the people that were reading it.

This did, however, give him quite the reputation to pen men’s metaphorical death certificates as he pleased. Renowned Nevada journalist Samuel Post Davis in his 1913 book “The History of Nevada,” wrote that Forbes, “Quick at the repartee, trained in the use of a rich and variegated vocabulary that contained every known expression of disapprobation, his bitter words often left scars that were slow to heal. After flaying a man and hanging his hide on the fence he would say, ‘Thus far we have been mild,’ and would give his victim another basting.”

Forbes was born truly for Nevada journalism. And although he strayed during his saloon stint, it is where his heart always lied. Davis went on to say, “Forbes declared that he would rather be the possessor of a handful of battered type and rattletrap press, with a power to say his mind as he pleased, than to be the owner of any other business establishment, no matter what the financial returns, and he proved it by deserting a prosperous business to return to an editorial position, from the emoluments of which he was only able to eke out a bare existence.”

DEATH, TAXES, & BM

There may be more than just two certainties in life. And in Forbes’ case, he probably experienced all three while finishing out his life in Battle Mountain.

While in Battle Mountain, Forbes started a newspaper called “Measure for Measure.” Not much is known about the paper, but it was short-lived, because on the morning of Oct. 30 1875, a friend found Forbes “lying stiff and cold across his shabby bed.”

Davis notes of his death: “He had fought a fight against all odds all his life, was one of the brightest geniuses the coast had ever seen, but he lacked the faculty of making and saving money and lived in communities where his mental brightness was more envied than appreciated.”

STILL A SECRET

So that’s it. That’s about everything that history remembers of a man who was too smart for his own good, and whose almost innocent intellect left him living a life of poverty, but a life of steadfast dignity; a man whose name now adorns plaques and history books next to Twain, Doten, and DeQuille, even though much of history has nearly forgotten him.

Forbes adequately and unknowingly wrote his own death quote, which is quite fitting for such a brilliant mind that was largely ignored:

“Death cannot be a matter of much moment to an editor—no thirty days’ notice required by law—it is the local incident of a moment, a few days as advertised on the fourth page, a few calls by subscribers not in arrears. A short, quick breath—then the subscription paper for burial expenses.”