Odyssey of a Ghost Town Explorer: Part 3

May – June 2016

Odyssey Of A Ghost Town Explorer

THIRD OF SIX-PART SERIES EXAMINES ABANDONED SETTLEMENTS OF SOUTHEASTERN NEVADA.

PART 3: THE WIDOW MAKER

BY ERIC CACHINERO

Some trips into the Nevada desert begin on a warm spring morning, with birds chirping, dry roads, and an overwhelming feeling of serenity and comfort. Sometimes the planets seem to align; ghost towns are abundant, the wildflowers are in full bloom, and the perfect day is just so easy to grasp. This is not one of those trips.

Some trips into the Nevada desert begin on a warm spring morning, with birds chirping, dry roads, and an overwhelming feeling of serenity and comfort. Sometimes the planets seem to align; ghost towns are abundant, the wildflowers are in full bloom, and the perfect day is just so easy to grasp. This is not one of those trips.

Painfully icy wind, subfreezing temperatures, and several inches of snow send insolent salutations as Editor Megg Mueller and I depart the Mizpah in Tonopah—a town that had enjoyed balmy spring weather merely two days prior. It’s an uneasy feeling traveling into the remote backcountry in the wake of an unexpected snowstorm, but sometimes you only get one shot at a trip like this, and we are taking it.

MUDDY WATERS

As we travel east on U.S. Route 6, heavy snow blankets nearly every square inch of terrain as far as the eye can see. Normally I would welcome Mother Nature’s gift of desert moisture, but it really couldn’t have come on a worse day as far as we were concerned. We make an attempt to reach Silverbow—a remote ghost town with a location as enticing as its history.

As we travel east on U.S. Route 6, heavy snow blankets nearly every square inch of terrain as far as the eye can see. Normally I would welcome Mother Nature’s gift of desert moisture, but it really couldn’t have come on a worse day as far as we were concerned. We make an attempt to reach Silverbow—a remote ghost town with a location as enticing as its history.

The townsite is intersected by the Nellis Air Force Range boundary, and was platted in 1904 by none other than Nevada mining and banking magnate George Wingfield. Abundant gold, silver, timber, and water made Silverbow an ideal boomtown. But the settlement’s success was short-lived due in part to claim jumping and diminishing riches, and it faded in 1906. Rumor has it that the town’s newspaper, the Standard, printed an edition with the front-page ink laced with gold dust that supposedly assayed for $80,000 a ton.

The townsite is intersected by the Nellis Air Force Range boundary, and was platted in 1904 by none other than Nevada mining and banking magnate George Wingfield. Abundant gold, silver, timber, and water made Silverbow an ideal boomtown. But the settlement’s success was short-lived due in part to claim jumping and diminishing riches, and it faded in 1906. Rumor has it that the town’s newspaper, the Standard, printed an edition with the front-page ink laced with gold dust that supposedly assayed for $80,000 a ton.

Though our attempt is valiant, it fails, and it’s probably best that it does. We encounter impossibly muddy roads as soon as we leave the pavement, and given that the ghost town is approximately 30 miles from the highway, it would be foolish to continue.

IT’S ALIVE!

Back out on U.S. 6, we set our sights on Tybo, hoping that this ghost town was able to avoid a massive amount of snow. We’re half right. The roads are muddy but manageable, while the occasional fishtail of our SUV dampens hope that we might actually be able to reach a ghost town today. After some sliding around, we reach Tybo, and to our surprise, it’s alive.

We use the term living ghost town to describe almost-abandoned settlements in Nevada that still have some permanent residents, and Tybo certainly fits the bill. Stone structures, a mine frame, and several modern homes dot the canyon t at the ghost town resides in, complete with a small, friendly dog we appropriately call Tybo.

Initial mineral discoveries can be traced to 1870, when Ameri- can Indians supposedly revealed the location to prospectors. The town’s name was derived from a Shoshone word meaning “white man’s district.” The district remained relatively stagnant, however, until 1874, when the Tybo Consolidated Mining District was formed and the townsite established. Soon a post office, newspaper, saloons, and a Wells Fargo office sprang up, but the town would quickly become blemished by the xenophobia that was sometimes typical of the era.

Initial mineral discoveries can be traced to 1870, when Ameri- can Indians supposedly revealed the location to prospectors. The town’s name was derived from a Shoshone word meaning “white man’s district.” The district remained relatively stagnant, however, until 1874, when the Tybo Consolidated Mining District was formed and the townsite established. Soon a post office, newspaper, saloons, and a Wells Fargo office sprang up, but the town would quickly become blemished by the xenophobia that was sometimes typical of the era.

Though Tybo was known for being relatively civilized during its early years, it’s documented that racial tensions between European and Chinese workers became as unstable as aging dynamite. In 1875, conflicts had reached a detonating apex, causing the Chinese to be chased out of town with bullwhips and bullets because they agreed to cut Pinyon timber for less than the standard wage. By 1880, the mines had all but played out, and the town was nearly dead. Revival attempts were made many times throughout the decades, but none stuck completely.

DESERT BUGLE

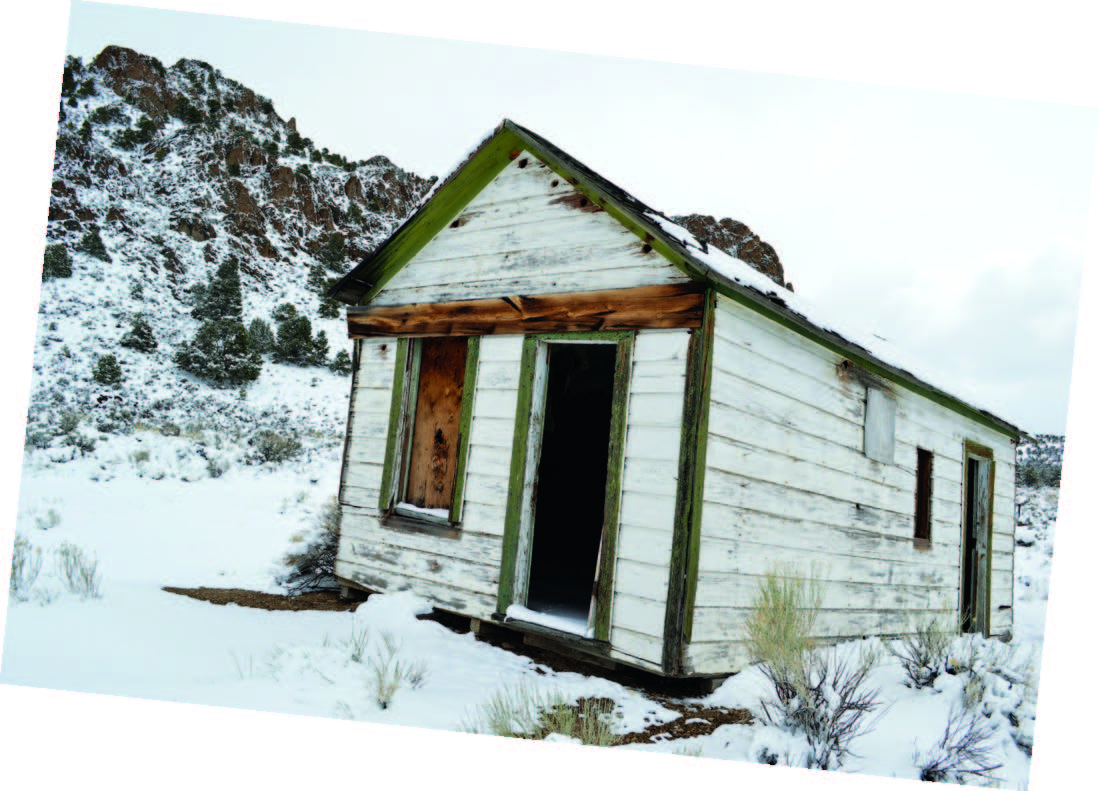

Intermittent flurries accompany our travels on Ne- vada’s Extraterrestrial Highway (State Route 375) toward the ghost town of Reveille. With temperatures now slightly above freezing, some roads are beginning to look a bit more promising than they did several hours earlier; at least we can see patches of mud now instead of just a blanket of snow. Alas, we’re busting through knee-high snow banks several miles from the highway, but luckily reach Reveille before it gets too disabling. A reveille is a signal given on a musical instrument—often a bugle—in the early morning to call military personnel to duty. Though no bugles can be heard during our visit, the occasional sharp crack and echo of ice falling from the town’s surrounding cliffs keeps us on our toes. A couple stone cabins and a solitary wooden one offer us some welcomed photo opportunities. They’re about all that’s left of Reveille, though there probably could have been entire collapsed structures blanketed in snow that we would have never seen unless we tripped over them.

Reveille is nearly as remote today as it was during its formation in 1866. Supplies had to be shipped from Austin and took six days to reach the town. At its peak, the district had 50 mines in operation and even a post office. Several million dollars of ore were processed in Reveille’s stamp mills before populations and production faded in 1880. We leave Reveille and make good time to the Midway Motel in Caliente where we call it a night. And by a twist of typical irony, it’s snowing when we arrive in Caliente—a town that’s name translates to hot in Spanish.

THE WIDOW MAKER

We awake to sunny skies—a much-needed relief. After tooling around in Kershaw-Ryan State Park for a bit, we’re on our way to Delamar. The town isn’t too far off U.S. 93, though the road—no longer snowy—gets a bit bumpy. A high-clearance vehicle with 4WD is a must-have on these types of trips.

I’ve never felt as much excitement reaching a ghost town as I do first laying eyes upon Delamar. Dozens of decaying structures, wooden houses, mine frames, three-story buildings, stone huts, tailings, and trash piles cover miles of hills. This place is truly a ghost town treasure where we could easily spend an entire day. Some ghost towns leave little clues to the scale of operations, but it’s easy to get an idea of just how massive Delamar was.

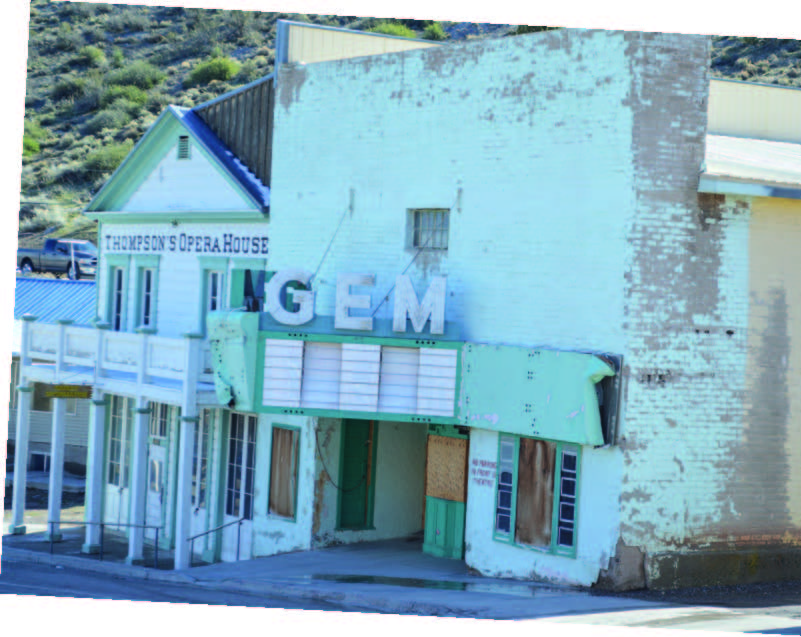

Pahranagat Valley farmers struck gold in the area that would eventually become Delamar in 1890-91. The discovery initiated an onslaught of eager gold bugs, including Captain John De Lamar of Montana, who purchased prime claims in 1893 in the amount of $150,000. Soon after his acquisition, the town of Delamar quickly rose from the ground, with many of the buildings constructed from native rock. Various businesses, a newspaper, post office, opera house, and 50-ton mill capable of handling up to 260 tons of ore per day provided work, but the American dream wasn’t all it was cracked up to be.

Because of improper ventilation and high silica content in the mines, dust became deadly. Silicosis left miners unlucky enough to inhale the dust with fatal symptoms, which included chronic coughing spells. The situation was so serious that the lethal particles became known as “Delamar dust,” and the town was labeled “The Widow Maker.”

By 1897, Delamar’s population reached 3,000, and during this time, the town was the largest ore producer in the state. A fire took its toll in 1900, and shortly after Captain De Lamar sold his mines, which had yielded a whopping $8.5 million in gold. By 1909, mining had ceased and except for a small revival from 1929-34, the town became a ghost.

ALL HAIL PIOCHE

Megg and I soon realize we’ve spent nearly half a day in Delamar. We explore some petroglyphs at nearby dry Delamar Lake before heading back to civilization and slowly making our way to the Overland Hotel & Saloon in Pioche for the night. To stress one final point concerning the absolute absurdity of changing weather patterns during our trip, it snowed, hailed, and rained on us in Pioche. I thought we had played it safe by heading south for this trip, but was remind- ed it’s imprudent to assume anything when it comes to Nevada’s backroads. In all, though, no widows were made during our careen through desert snow, so we came out on top this time.

Keep an eye on this column for the remainder of 2016 as we explore ghost towns all across the state. Have a ghost town you think we need to see? Email [email protected] and let us know about it.

Nevada Magazine’s Ghost Towns & Historic Sites map is on sale now! This Nevada treasure comes jam-packed with historical information, color photographs, ghost town trip itineraries, park and territory information, fun facts, a large state map showing the locations of hundreds of ghost towns, and more.

Nevada Magazine’s Ghost Towns & Historic Sites map is on sale now! This Nevada treasure comes jam-packed with historical information, color photographs, ghost town trip itineraries, park and territory information, fun facts, a large state map showing the locations of hundreds of ghost towns, and more.

Modeled after our 1987 ghost towns map, the updated publication includes everything from mini-maps to historical ghost town photos, safety tips to pertinent contact information. Our historical tidbits keep travelers and explorers entertained and knowledgeable

while on the road as they learn about some of Nevada’s oldest and most interesting sites. With more than 600 ghost towns in the Silver State, deciding which ones to visit can be daunting. But, the information provided in this map can help get you there, and is a great choice for both ghost town novice and the seasoned traveler. Nevada Magazine’s Ghost Towns & Historic Sites map is available for preorder on our website at nevadamagazine.com or by calling Nevada Magazine Circulation Manager Carrie Roussel at 775-687-0610. Shipping begins mid-May.