Odyssey of a Ghost Town Explorer: Part 8

March – April 2019

Chapter 2, Part 8: Living on the Edge of Death

BY ERIC CACHINERO

More than 100 years ago, southern Nevada pioneers and prospectors spent every day surviving on the razor-edge of death. Mucking, sweating, and blasting in sweltering summers and stinging winters. They moved earth as they dug their dwellings into the sides of mountains, sleeping in ramshackle huts made of rock and wood. They tossed fire and brimstone over their shoulders with shovels and pickaxes as they sought to manifest their destiny. They took up arms against Mother Nature, who tried her hardest each and every day to convince them that living there wasn’t worth it, but they only thumbed their noses and kept digging.

In 1913, a couple years after the Bullfrog mines on the edge of Death Valley ran completely dry, the highest temperature ever recorded on earth—a blistering 134 degrees—was measured just a couple dozen miles away at Furnace Creek, California.

What brought them to this hell? To this almost uninhabitable barren wasteland? To the edge of this monumental valley, where temperatures rival those of the Sahara and Great Victoria deserts?

CROAK

These are the thoughts that dance in my mind as I awake in a climate-controlled hotel room in The Gateway to Death Valley—Beatty—before taking a hot shower, brushing my teeth, and scarfing down a hot breakfast. Nevada Magazine Editor Megg Mueller and I load our vehicle up with snacks and gallons of water before driving to the edge of Death Valley while listening to the radio and wandering from ghost town to ghost town. I think to myself: “wimps…”

It wasn’t always like this in this strange part of the world that, for good reasons, warrants the name Death Valley. Not long ago, the men and women that lived in these areas probably had a much different morning routine, and it seems almost sacrilege that we’re encroaching upon their territory in such a manner. They actually survived upon this land that we are now simply tourists observing.

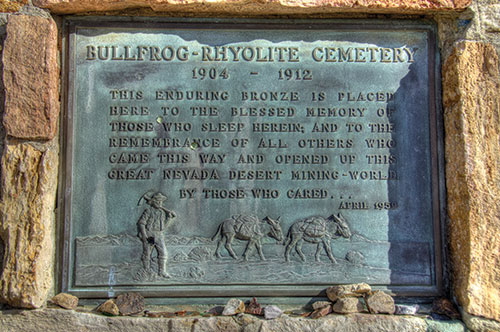

Such is the way it was when gold was discovered in the Bullfrog District on Aug. 4, 1904, kicking off one of the largest gold booms in Nevada history. One of the discoverers, Shorty Harris, later described of the find, “I’ve seen many gold rushes in my time that were hummers, but nothing like that stampede…It looked like the whole population of Goldfield was trying to move at once…That was the start of Bullfrog and from then things moved so fast that it made us old timers dizzy.”

In 1905 Bullfrog (then a tent village named Orion), optimism swirled with the dust in the air. Towns were popping up all across the region (Beatty, Rhyolite, Amargosa City, and Gold Center), and claims were staked like musical chairs. The major townsite at the time was Rhyolite, though nearby Bullfrog briefly made a run for supremacy. Bullfrog housed 1,000 people and boasted a bank, jail, chamber of commerce, hotels, post office, and a business district, which due to the town’s close proximity eventually converged with Rhyolite’s. By 1906, Rhyolite would win the power struggle and many businesses in Bullfrog closed up shop and moved a mile up the road to be closer to the booming town. Bullfrog still retained residences, though those too would fade when the mines started to run dry in 1909.

Not much is left of Bullfrog today, except for an old jailhouse and a couple other stone structures. The jailhouse is in surprisingly great shape for a more-than-100-year-old building, and still contains the original window bars. Just up the road lies the original Bullfrog mine, and just down the road lies the cemetary. Megg and I snap a few shots and head out into the great unknown, as we drive into Nevada’s small section of Death Valley National Park.

UNNECESSARY DICTIONARY

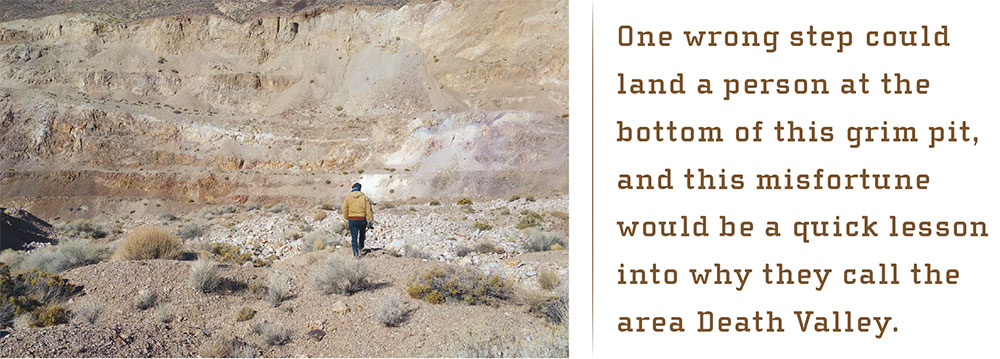

As we mosey our way deeper into the park, it’s not hard to imagine what this area used to look like when thousands of starry-eyed prospectors descended here during the Bullfrog boom. The typical Nevada beauty abounds, but signs of life—modern and historical—are tucked deep away in this place, hidden amongst the mountain canyons and crags. Save some concrete ruins in the distance, we see nothing of ghost towns until we park atop a hill and start walking toward where we hope to find the ghost town of Gold Bar. Walking may be putting it incorrectly, though, because it becomes apparent that we’ve stumbled upon an open-pit mine, and the only way to avoid an unfortunate misstep is better described as tip-toeing.

Gold Bar popped up around the same time as many of the other mining towns in the region, though its success fell short. At its peak, only about 50 people called the town home, though the nearby Homestake-King Mine and Mill did produce some ore until it closed in 1909.

Megg and I explore the absolutely massive open-pit mine, making sure to exercise extreme caution. One wrong step could land a person at the bottom of this grim pit, and this misfortune would be a quick lesson into why they call the area Death Valley.

The real nugget is located on the hillside just northeast of the mine. Remnants of the mill sit high above the valley on a steep hillside. Amid the concrete foundation are an aggregation of scattered bricks and metallic trash and treasures, signs that the operation was fairly large at its peak. As we hike up to the mill, I make a joke to Megg about how hiking up the steep hill reminds me of chukar hunting, only unlike chukar hunting, once we reach the top of the hill, there’s actually something waiting for us there. Ghost towns can’t usually stick their tongues out at you as they fly away.

SAHARA HARE

There’s a “Looney Tunes” episode that comes to mind as we reach our next ghost town: Currie Well. It starts with Bugs Bunny searching for Miami Beach, only to find out he’s actually in the Sahara Desert. He walks for miles trying to find the Atlantic Ocean, and eventually finds a shallow puddle, dives in, and lucklessly buries his face in the mud on the bottom.

I feel like Bugs. I’m searching frantically for the place I’ve heard described as an oasis in the desert. I’m half-expecting palm trees and inflatable flamingos to be lining a crystal-clear Olympic-sized swimming pool. After about a half hour of searching, I eventually find the life-giving spring, only instead of Miami Beach, I find a rusty pipe protruding from a frozen mud puddle about 5-feet in diameter.

Though Currie Well doesn’t live up to my unrealistic expectations, the site actually served a monumentally important purpose in its time. The spring water was originally used to revive thirsty stage animals and passengers making their way between Rhyolite and Goldfield. Entrepreneurs tried their luck at charging passersby for access to the spring now and again, though all attempts took on water. In 1907, the well acted as a work camp for the crew constructing the Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad.

In addition to the well, scant metallic remains and a primitive beehive furnace mark the site, though there’s not much else to explore.

That’s all, folks.

MALT & MARBLE

MALT & MARBLE

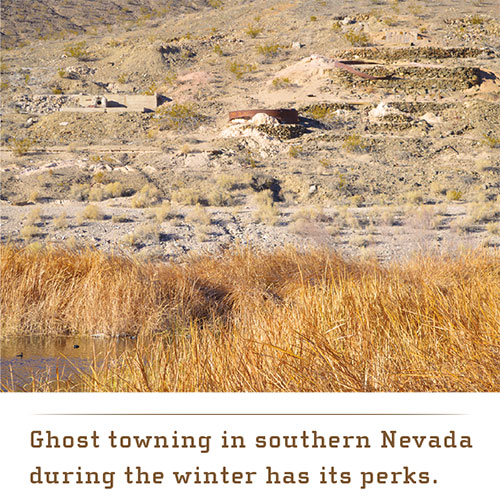

As mid-afternoon sets in, we decide it’s time to leave the park and head south to see a couple more ghost towns before the sun sets. Ghost towning in southern Nevada during the winter has its perks (we didn’t roast ourselves in Death Valley), but the sun sets at around 5 p.m., meaning we have to zoom if we’re to check off any more on our list. Our zooming leads us first to Gold Center, located just south of Beatty.

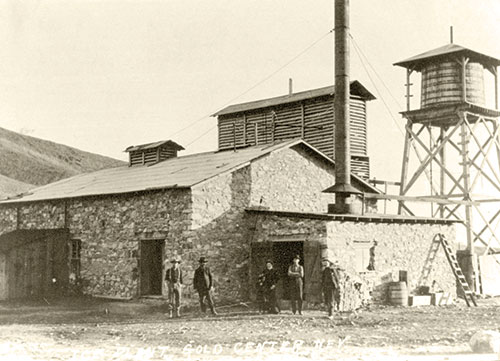

Gold Center is ironically named because, well, there was never any gold discovered there. In 1906, the site did serve as the terminus of the Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad and the company did maintain a yard and freight depot there. Gold Center also operated briefly as the railhead for Rhyolite. At its peak, the town had many of the usual staples (bank, newspaper, hotel, saloons, etc.), but what made Gold Center special was the malt and hops it mixed and the sacred suds it supplied to the surrounding camps. The Gold Center Ice & Brewing Co. was the first brewery in the area and held its operations in a large stone structure. The town also boasted a 30-stamp mill, though as many of the surrounding towns faded, so did Gold Center.

Remnants of the brewery and mill still exist at the site, though it’s hard for Megg and I to tell which is which. The site is located next to Bombo’s Pond—a recreational fishing pond right off U.S. 95. Visitors to the site can spend a half hour exploring the ghost town, or spend a whole day relaxing, picnicking, and fishing.

We head a little further down the road before coming to the next just-off-the-highway ghost town: Carrara.

Like Gold Center, Carrara also didn’t produce any gold. The town was unofficially founded around 1904, and was centered around marble quarrying. The town was most likely named after Carrara marble—a high-quality marble mined in the city of Carrara, Italy. Though original Nevada deposits were too fractured and resulted in pieces too small to be desirable, additional deposits were later discovered, and in the early 1910s, a townsite was platted and the American Carrara Marble Co. was created. In May 1913, Carrara was dedicated, and the celebration featured a baseball game, live band from Goldfield, and swimming in the town pool. A small railroad was completed to bring marble from the quarry up on the hill above town to the Tonopah & Tidewater station, before it made its way to Los Angeles to be cut and polished. Due to regional strife caused by a lack of metal production, the town faded completely in the mid-1920s.

Megg and I explore some badly vandalized concrete structures for a bit, only to later learn that they are not, in fact, Carrara. The most prominent concrete structures visible from the highway are the result of a defunct 1930s cement company. The actual ghost town of Carrara is located about 1.5 miles south of the concrete structures, and all that remains are several foundations and a road up to the old marble quarry.

MR. NEVADA’S CABIN

With the sun hanging heavy in the sky, we scurry southward still into the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, where we’re looking for our final historical structure of the night: Longstreet Cabin.

Nevada rancher, saloonkeeper, gunslinger, and prospector Jack Longstreet built this historic cabin in 1895. Longstreet epitomized the desert frontiersman, homesteading locations around the state including Moapa Valley. He opened a saloon in the now ghost town of Sylvania in 1890, and it was there that he helped Paiute mineworkers get an honest pay. Longstreet built a reputation as a charismatic protector of the downtrodden, as well as a feared gunman who wasn’t afraid to settle an argument with a pistol. He is buried in Belmont alongside his wife.

Longstreet Cabin is less of a ghost town and more of a ghost hideout, though its connection to Nevada history is significant. Megg and I explore the cabin, which was reconstructed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the original location using stones from the original building, before enjoying a vibrant desert sunset, and heading back to Beatty for the night.

DISORIENTED

We’re on the road early the next morning headed north for another whole day of ghost towning—a somewhat intimidating thought considering we have already seen so much. We head north on 95 before veering toward the ghost town of Tokop, located near Gold Point. We ascend from the valley floor following a winding dirt road higher and higher into the mountains before reaching the top. We park next to a radio tower and start searching for Tokop, unsuccessfully. Though we can’t find the ghost town, we’re rewarded with some incredible 100-mile views before continuing on toward our next ghost town: Oriental.

Oriental was founded when prospector Thomas Shaw discovered gold in 1864. The operation was small, though it yielded some of Nevada’s richest gold samples by concentration. Because of the town’s remoteness and lack of water, it never grew very large, dying out completely by 1900.

We poke around some abandoned (and dangerous) mine shafts and a cool old cabin before pressing on.

The road leads us to the semi-ghost town of Gold Point, before we continue on to Stateline.

Stateline, sometimes referred to as Gold Mountain, was also discovered by Shaw, though he abandoned his claims. The area was not exploited much until 1880, when the Stateline mine was considered one of the best in the state. By 1881, the townsite had all of the usual fixings, along with a 10-stamp-mill built by the Stateline Mining Co., and a water pipeline connected to nearby Tule Canyon. The town boomed for a decade before it petered out, with a couple occasional hiccup revivals over the years.

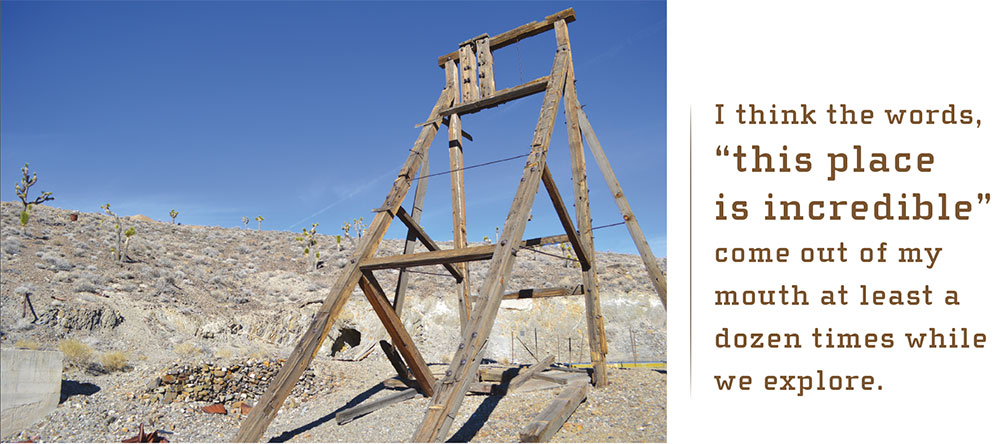

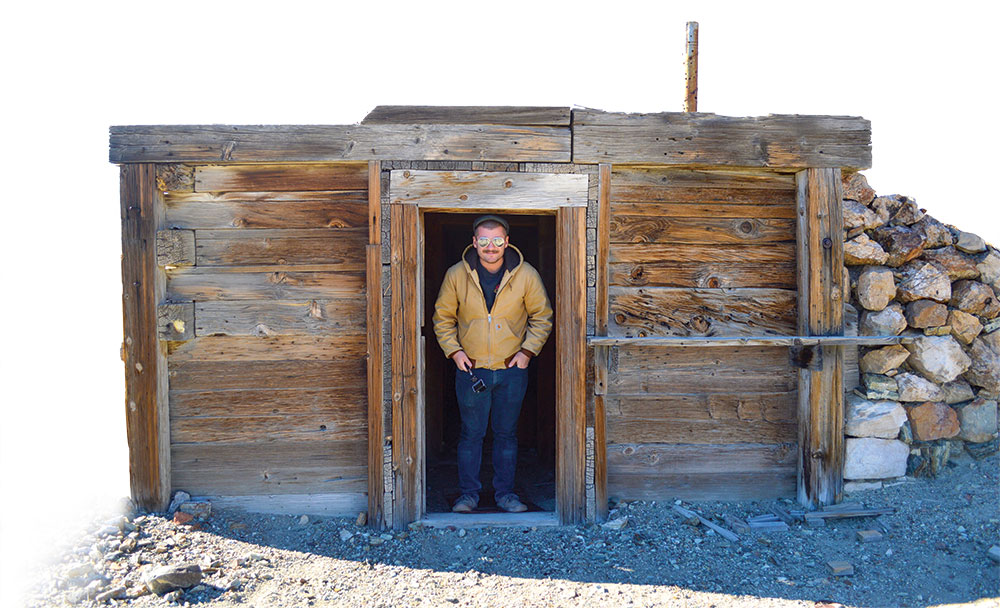

Megg and I are awestruck when we pull up to Stateline and see the vastness of the explorable structures that stretch for nearly as far as the eye can see. Headframes, wood and stone domiciles, mill remnants, mine shafts, cabins—a person could spend an entire day poking around the town’s remains. We walk from structure to structure giving our best guess to what is was and how it worked. Angled mine shafts disappear beneath the earth, offering us a quick peak from above that for all we know could be an infinitely deep hole. An especially interesting feature is a double-entrance vertical shaft, the top of which is structurally supported by large timbers.

I think the words, “this place is incredible” come out of my mouth at least a dozen times while we explore, as probably do, “I’m bummed we have to leave,” because we have no time to waste and a couple more ghost towns to see.

ROUGHING IT ROADSIDE

We meet up with State Route 266 and head west through Lida toward the ghost town of Palmetto. The road is uncharted territory for the both of us, and the views are special. This cozy corner of the state seems somewhat untouched by human hands, and you don’t have to search for solitude. A state historical marker lets us know we’ve reached our destination.

Palmetto was formed in 1866 by gold and silver prospectors who thought the local Joshua trees were related to the palm tree, hence the name. A 12-stamp mill was built, though the operation was short lived. A brief resurgence in the late 1860s again resulted in abandonment. A second revival in the early 1900s resulted in a tent camp of around 200, and the town boomed before dying out in the 1920s.

The mill foundation and stone structures are visible from the road, and we crawl around them before backtracking a bit and heading off into a snowy Sylvania Canyon.

Sylvania resulted from lead and silver discoveries made in 1869. The town boasted several celebrities, including Death Valley borax miner Christian Zabriskie who operated a general store, as well as the saloon owned by the aforementioned Jack Longstreet. A 30-ton smelter was built around 1875, though it only ran for a few years. Small mining operations have occurred in the canyon sporadically, even up to today.

We traverse a snow-covered, steep, and windy road through the canyon, and we ignore our better judgement to just turn around and avoid getting stuck. We reach the Sylvania mine with a little bit of daylight to spare. The site is marked by small-scale active mining claims and a host of private mining equipment. Several old cabins can be found in a state of bad disrepair. We explore for a bit before the sunset sends us home.

UNCOMFORTABLE CREATURES

Modern comforts make us soft. Society takes for granted the basic commodities that were sometimes impossible to come by not too long ago. Furnace-heated houses replaced cold shabby tents, running water replaced buying it by the bucket full, combustion engines replaced dragging a donkey across a scorching desert, and indoor plumbing replaced the outhouse. Life was no doubt far less comfortable back then.

But that’s how it was. Toughness was a vital trait. People either adapted to the harshness of the Wild West, or suffered the fate of the alternative. That’s how it was day after day for the earliest Nevadans living on the edge of death.