The Race To Bullfrog

March – April 2018

The Race To Bullfrog

Two of America’s captains of industry clashed in this desert railroad battle.

BY FRANK WRIGHT

This story first appeared in the July/August 1992 issue of Nevada Magazine.

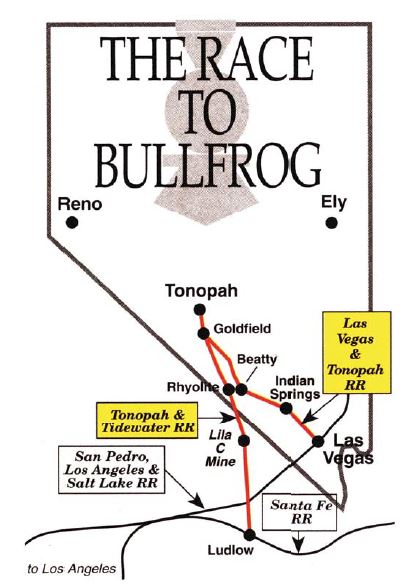

In 1905, two railroads began making a mad dash across the desert north of Las Vegas. The object of the race was to capture the heart and gold of the booming Bullfrog Mining District in central Nevada. It also proved to be a clash between two empire builders of the first stripe.

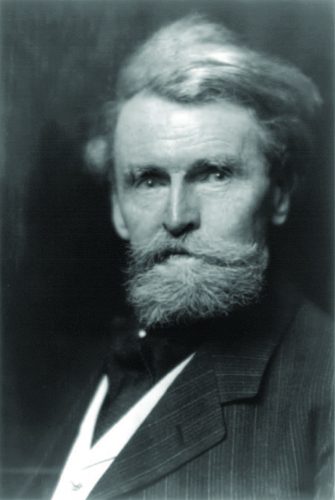

William Andrews Clark was a U.S. Senator from Montana who had made a fortune in mining and finance. Clark had just brought his San Pedro, Los Angeles, and Salt Lake Railroad through southern Nevada, creating the town of Las Vegas in the process. His rival was F.M. “Borax” Smith, an equally formidable char-acter whose Death Valley borax dominated the world market with its “20-mule team” trademark.

Both Smith and Clark had sensed the potential rewards of a railroad connecting the new mines at Rhyolite and other Bull-frog camps with southern California. At first the two men were drawn together as comrades in commerce, but soon their paths parted, and they embarked on a fierce competition to bring rails to Rhyolite.

DEEP VEIN OF COMPETITION

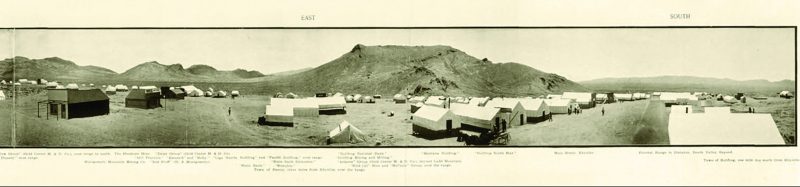

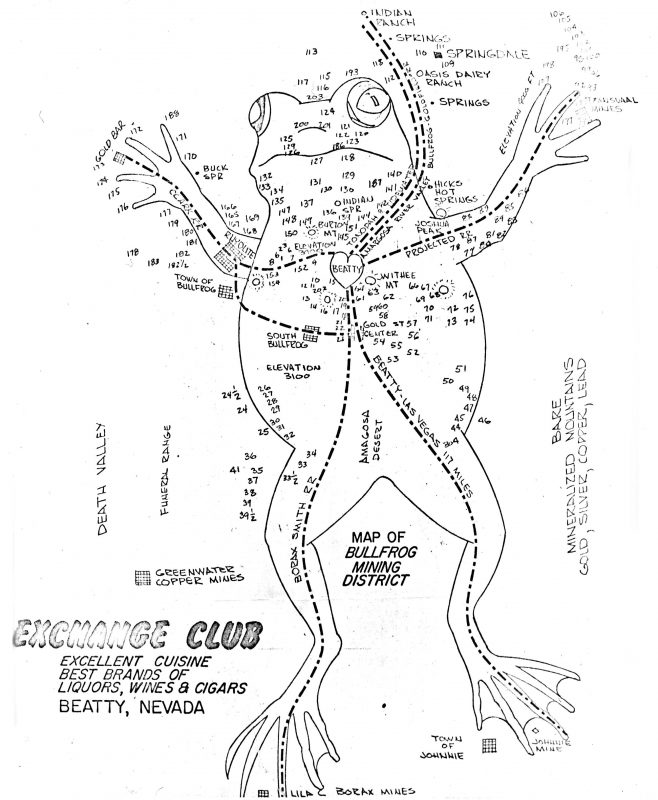

Their rivalry had its roots in the central Nevada mining boom that began with the Tonopah silver discoveries in 1900. Two years later, prospectors uncovered a vein of rich gold ore to the south, and Goldfield was born. Soon the Bullfrog District near Beatty added fuel to the mining fever. Rhyolite, the district’s most important city, sprang up in January l905.

Las Vegas valley was also the scene of frenzied activity. In JJanuary1905, a small ceremony involving the “driving” of a thumb-tack-size gold spike marked the completion of Clark’s San Pedro, Los Angeles, and Salt Lake Railroad. The following May, a public auction of lots established the town of Las Vegas.

Meanwhile, Smith, Clark, and others began efforts to connect the Bullfrog District to the larger rail network. The advantage seemed to lie with the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad (T&G), which already provided a link to the transcontinental line at Reno. Philadelphia investors, who controlled the T&G as well as most of the important Tonopah mines, organized the Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad (BG). Because of internal problems, however, the BG didn’t begin laying rails until May 1905.

It was too late. Smith and Clark, determined industrialists both, had already left the gate.

Acquaintances of the two rivals described Smith and Clark in almost identical terms. Each was said to be “not a large man” but an “imposing figure.” The handlebar-mustachioed Smith and the bristly-bearded Clark were both proud of their rough-hewn origins. Smith transported the wood cabin he built while serving as a woodcutter near Candelaria to his lavish estate in Oakland, California. Of Pennsylvanian Clark, the “Las Vegas Age” rhapsodized that “he has not spent his life in the strife of Wall Street, but on the wind-swept plains … He has remained in close kinship with the people of the west.”

Even the routes that brought the two men together in 1905 offer curious parallels. Twenty-one-year-old Francis Marion Smith left his native Wisconsin in 1867 to knock around the mining camps of Montana, Idaho, and Nevada. William Andrews Clark had arrived in Montana in 1863 by a more circuitous route— law school at Iowa Wesleyan, school teaching in Missouri, and mucking out mines in Colorado.

Even the routes that brought the two men together in 1905 offer curious parallels. Twenty-one-year-old Francis Marion Smith left his native Wisconsin in 1867 to knock around the mining camps of Montana, Idaho, and Nevada. William Andrews Clark had arrived in Montana in 1863 by a more circuitous route— law school at Iowa Wesleyan, school teaching in Missouri, and mucking out mines in Colorado.

Each man had made his initial fortune in mining. Clark amassed enough money from placer mining in Montana to turn to merchant banking. From such activities as buying and selling gold dust, milling lumber, mining copper, and trading in flour and tobacco, his financial empire eventually expanded to include a large wire works in

New Jersey, a sugar processing plant in Southern California, and the enormously profitable copper mines near Jerome, Arizona.

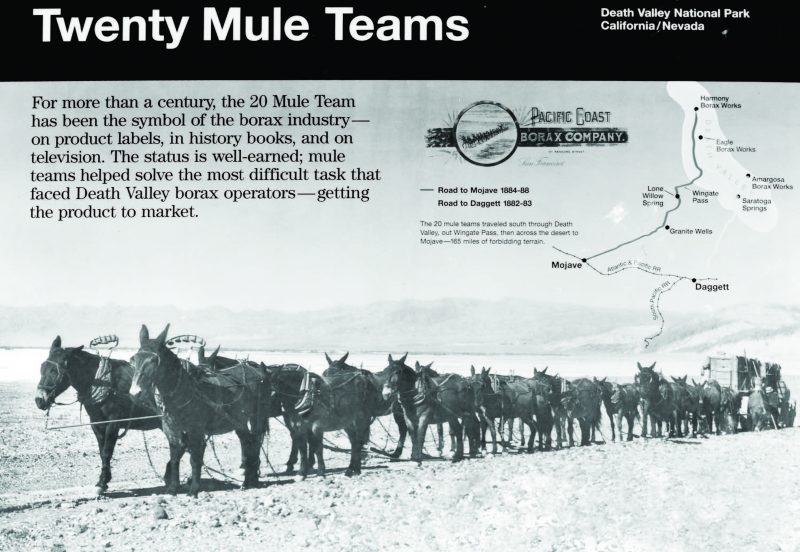

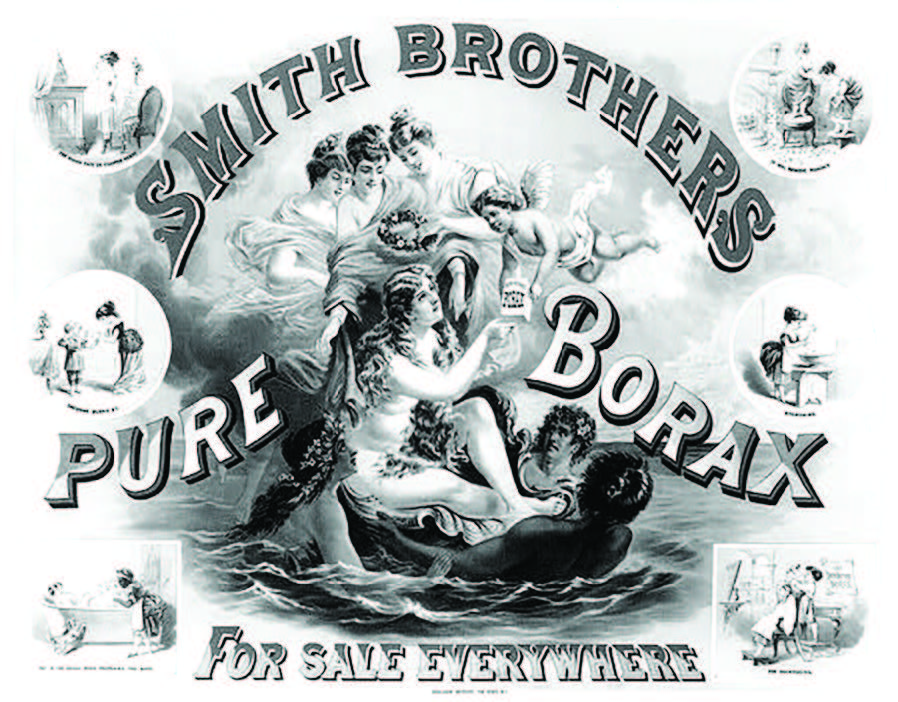

Smith’s fortune derived from almost single-handedly developing the borax industry in America. While laboring as a woodcutter at the western Nevada mining camp of Candelaria in 1872, he discovered borax deposits at nearby Teel’s Marsh. Working with William Coleman of the Pacific Borax Company, he put together and built up the giant Pacific Coast Borax Company (PCB) by 1890. This was done in part by opening a New York office to promote the multiplicity of uses—from soap-to glass-making to whatever use the then little-known mineral could be put. Six years later, the firm went multinational through a merger with an English company. By then, PCB controlled roughly 85 percent of the domestic market, and its “20-mule team” identity was familiar worldwide. As a corporate titan, Smith was a force to be reckoned with.

Clark was no slouch, either. His vast fortune and power paled beside that of E.H. Harriman of the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific, yet he had battled Harriman to a draw in building a raillink between Los Angeles and Salt Lake City. The so-called “Clark-Harriman War,” fought in the field with pickaxes and shovels as well as in the courts, between 1900 and 1905, ended with Clark and Harriman each controlling 50 percent of the new San Pedro, Los Angeles, and Salt Lake Railroad.

Meanwhile, Clark had engineered his election as a U.S. Senator from Montana. Although he was first elected by state legislators in 1899, the Senate balked at seating him because of extensive fraud and bribery in the election, a practice that was not unusual in the days before the direct election of senators. Undeterred, Clark obtained re-election in 1901 and was duly seated.

A PLAN GOES OFF TRACK

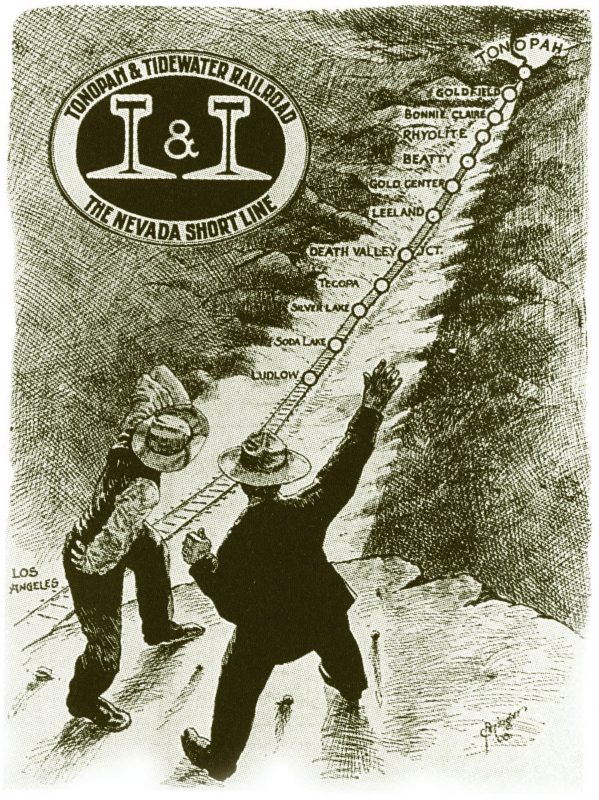

The two men’s race by rail could be said to have begun with a chance meeting at San Francisco’s posh Pacific Union Club in April 1905. Smith told the senator that he needed to build a railroad immediately. Some of Smith’s borax deposits were about to give out, so he had to turn to his undeveloped Lila C Mine on the edge of Death Valley. Rails from Ludlow, California, on the Santa Fe Railroad to the Lila C would replace the picturesque and reliable, but slow, 20-mule teams. The new line was the Tonopah and Tidewater. Clark proposed an intriguing alternative. Smith could connect his Tonopah and Tidewater (T&T) to the Clark line at Las Vegas instead of reaching farther south to the Santa Fe. The curves and grades would be easier and the distance considerably shorter. Clark also promised that he would match the Santa Fe’s price on the delivery of rails and ties. Satisfied that he had struck a mutually advantageous deal, Smith promptly sent surveying and grading crews to Las Vegas, and work began on the grade northwest to Indian Springs. But Clark had outmaneuvered Smith. The first hints of a double cross came when Clark workers began surveying an auto road parallel to the T&T grade. Although the road quickly proved a fiasco as the autos kept breaking down, there was a more serious omen— Clark was charging Smith considerably more than he had promised for the delivery of rails and ties. The final wrench in Smith’s plans came in August, when Clark’s representatives refused to allow the T&T a connection to their road at Las Vegas.

The two men’s race by rail could be said to have begun with a chance meeting at San Francisco’s posh Pacific Union Club in April 1905. Smith told the senator that he needed to build a railroad immediately. Some of Smith’s borax deposits were about to give out, so he had to turn to his undeveloped Lila C Mine on the edge of Death Valley. Rails from Ludlow, California, on the Santa Fe Railroad to the Lila C would replace the picturesque and reliable, but slow, 20-mule teams. The new line was the Tonopah and Tidewater. Clark proposed an intriguing alternative. Smith could connect his Tonopah and Tidewater (T&T) to the Clark line at Las Vegas instead of reaching farther south to the Santa Fe. The curves and grades would be easier and the distance considerably shorter. Clark also promised that he would match the Santa Fe’s price on the delivery of rails and ties. Satisfied that he had struck a mutually advantageous deal, Smith promptly sent surveying and grading crews to Las Vegas, and work began on the grade northwest to Indian Springs. But Clark had outmaneuvered Smith. The first hints of a double cross came when Clark workers began surveying an auto road parallel to the T&T grade. Although the road quickly proved a fiasco as the autos kept breaking down, there was a more serious omen— Clark was charging Smith considerably more than he had promised for the delivery of rails and ties. The final wrench in Smith’s plans came in August, when Clark’s representatives refused to allow the T&T a connection to their road at Las Vegas.

Was Clark’s San Francisco proposal a deliberate ploy or simply a change of heart occasioned by visions of his own road? Historians are uncertain. Whatever the answer, Clark’s new Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad (LV&T) began extending the partially graded T&T route in December, while the T&T reverted to Smith’s original plan and began laying tracks north toward Death Valley from Ludlow.

Was Clark’s San Francisco proposal a deliberate ploy or simply a change of heart occasioned by visions of his own road? Historians are uncertain. Whatever the answer, Clark’s new Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad (LV&T) began extending the partially graded T&T route in December, while the T&T reverted to Smith’s original plan and began laying tracks north toward Death Valley from Ludlow.

Both roads made swift progress at first. The LV&T reached Indian Springs by February 1906, and Smith completed 75 miles of track by May. From Indian Springs, Clark had clear sailing and reached Beatty—the Bullfrog District’s distribution center—in October. Smith’s crews still had to negotiate 12 arduous miles of Amargosa Canyon south of Tecopa.

Even though the two roads had begun almost simultaneously, the Smith-Clark race to Bullfrog was soon over. The first LV&T locomotive pulled into Rhyolite—where the old LV&T depot still stands—in December 1906 while T&T crews were still battling the heat in the canyon.

In Amargosa Canyon, members of Japanese and Mexican work crews met tragic ends; the “Goldfield News” reported that workers were “dying off like flies.” The T&T didn’t reach Tecopa until May 1907 and only made connections with the Lila C Mine in August, nearly a full year after starting. When the T&T finally reached the outskirts of Beatty in October, the LV&T was already completing its line to Goldfield.

LAST BUT NOT LEAST

Clark may have won the race, but it turned out to be an empty victory. The LV&T made a profit only in its first year. The effects of a national financial panic struck Nevada mining camps in late 1907, and the rich ore veins at Rhyolite proved shallow and were already petering out. Clark’s LV&T was virtually forgotten during the war years of 1914-18, and it was officially shut down after the war.

Clark may have won the race, but it turned out to be an empty victory. The LV&T made a profit only in its first year. The effects of a national financial panic struck Nevada mining camps in late 1907, and the rich ore veins at Rhyolite proved shallow and were already petering out. Clark’s LV&T was virtually forgotten during the war years of 1914-18, and it was officially shut down after the war.

The LV&T did achieve, however briefly, the first and only interior rail link between Las Vegas and Reno, though it took five railroads to span the distance. The linkup was completed when John and Arthur Brock’s Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad limped into the Bullfrog District in June 1907.

Borax Smith may have been the last to arrive, but he had the satisfaction of outlasting the others. Even after the Lila C ores gave out in 1914, the Smith route had an edge over the LV&T. The T&T, touted as “The Nevada Short Line,” had taken over the operation of the financially troubled Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad and had a more direct route to the coast for Goldfield freight.

Borax Smith may have been the last to arrive, but he had the satisfaction of outlasting the others. Even after the Lila C ores gave out in 1914, the Smith route had an edge over the LV&T. The T&T, touted as “The Nevada Short Line,” had taken over the operation of the financially troubled Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad and had a more direct route to the coast for Goldfield freight.

As the Goldfield ores also gave out, the T&T gradually faded, and the BG folded in 1928. The development of Furnace Creek Inn in Death Valley by Pacific Coast Borax provided some tourist income for the T&T in its declining years, but it too finally ceased operation in 1940.

The railroading ambitions of Smith and Clark left other legacies besides their race to Bullfrog. Smith’s T&T opened borax country to the traveling public, and that led to the establishment of Death Valley National Monument in 1933. Clark’s mainline created Las Vegas—back then, a dusty division point in the desert—and today his name is honored by Nevada’s most populous region, Clark County.