Then & Now: Through the Lens

March – April 2015

Time has both serious and subtle effects on Nevada.

BY NEVADA MAGAZINE

THEN: NEVADA HISTORICAL SOCIETY; NOW: ERIC CACHINERO

PHOTOGRAPHERS: ERIC CACHINERO, NANCY GOOD, GREG MCKAY, MEGG MUELLER

Take a second to look out the closest window to you. What do you see? Swaying trees? A busy street? A sagebrush scene? There’s a chance that whatever you’re seeing out that window looks much different than it did 80, 100, or even 150 years ago. But, like many meticulously preserved aspects of the Silver State, there’s a chance it may not look too different. Just take a look at the photo of the 1897 Nevada Legislature and staff on the steps of the Nevada State Capitol above; more than 100 years and not much—other than the people—has changed.

To explore some of these differences, we visited various locations across the state to compare what they looked like then, to what they look like now. So let’s travel Nevada in both time and space, and see just how many things have changed, and how many have stayed the same.

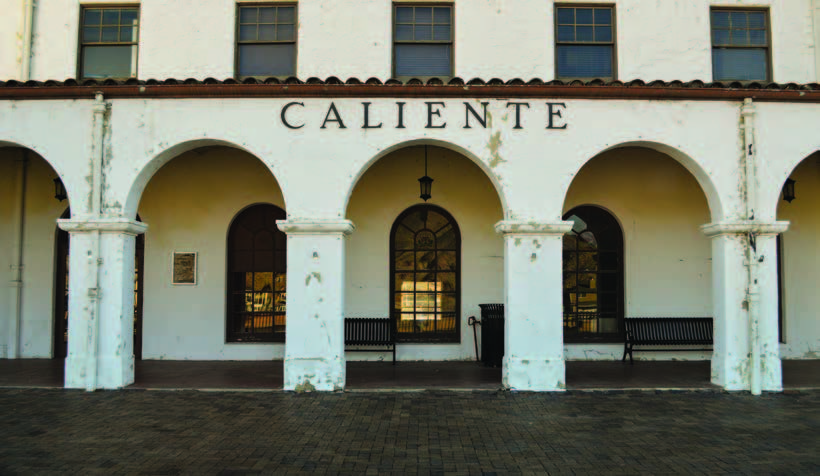

CALIENTE RAILROAD DEPOT

THEN

The Caliente Railroad Depot was constructed by the Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad in 1923, and acted as the railroad’s division point between Los Angeles and Salt Lake City. Eventually, diesel locomotives would replace steam, and the depot was no longer needed.

NOW

The depot is now Caliente’s civic center, and holds the town’s government office, museum, and library. Freight trains still pass on the tracks alongside the depot, though the last passenger service ended in the 1990s.

BELMONT COURTHOUSE

THEN

Constructed in 1875-76, the Belmont Courthouse served as the Nye County courthouse until 1905, when the county seat was moved to Tonopah. By 1900, silver was drying up in the area, causing mines to close, and the town began to dwindle.

NOW

Thanks to recent efforts by Friends of the Belmont Courthouse—the group dedicated to preserving this Nevada landmark— the courthouse looks remarkably similar to what it did in its prime. On a trip in summer 2014, photographer Greg McKay and a group of ghost town enthusiasts recreated this shot in front of the courthouse.

COLORADO RIVER

THEN

At the foot of Eldorado Canyon in southern Nevada during the late 1800s, steamboats could often be seen making their way up the Colorado River.

NOW

The area has now become a popular destination for aquatic activities, cliff jumping, and fishing.

RHYOLITE BOTTLE HOUSE

THEN

From 1905-06, prospector Tom T. Kelly built the famous bottle house in Rhyolite, using approximately 30,000 (50,000 by some accounts) bottles that were scavenged from the town’s saloons.

NOW

The bottle house was restored in 1925 by Paramount Pictures for a silent film called “The Air Mail,” and again in 2005. Today, it is owned and maintained by the Bureau of Land Management.

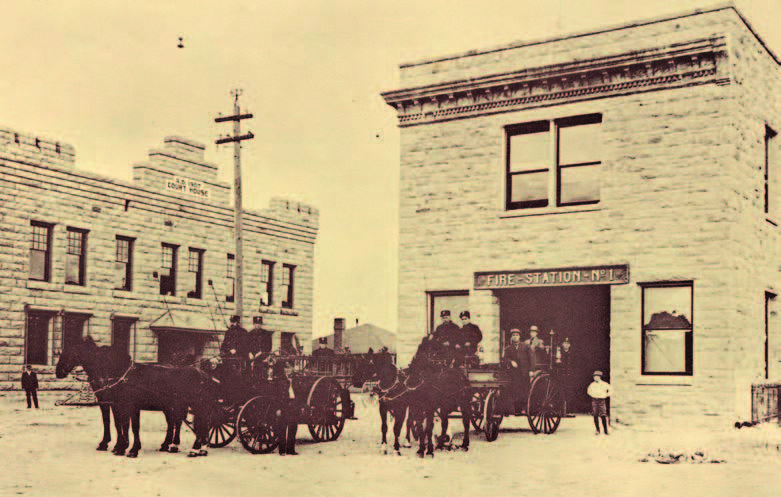

GOLDFIELD

THEN

The Esmeralda County Courthouse and Goldfield Fire Station No. 1 were both constructed in 1907.

NOW

Though Goldfield is sometimes considered a ghost town, small shops line the streets and show promising commerce. The courthouse remains in service to this day, and the fire station was operational until June 2002.

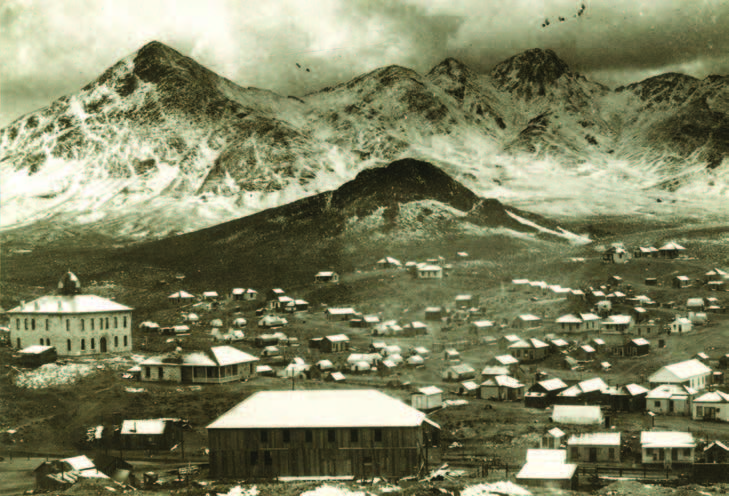

TONOPAH

THEN

After gold was discovered in Tonopah in the 1900s, construction of buildings including the Mizpah Hotel and Nye County Courthouse followed. The new courthouse—built in 1905—is in the far left of the photo.

NOW

The Tonopah Historic Mining Park and the Central Nevada Museum are just a few of the many historical treasures in the town.

HISTORIC BOULDER THEATRE

THEN

The Boulder Theatre was constructed in 1933 by Fox Theatres. At the time, it was the only air-conditioned building in town, and many Hoover Dam workers would pay 25 cents to enjoy a few hours of sleep in a cool room.

NOW

The theatre closed briefly in the mid-1990s, before being renovated by its current owners, Desi and Amy Arnaz. Today, the theatre hosts events including a film festival, Chautauqua, and ballet performances.

EUREKA OPERA HOUSE

THEN

In August 1879, the great Main Street fire in Eureka destroyed a building called the Odd Fellows Hall. In its place, the Eureka Opera House was constructed, and, in 1880, it was used for the first time for the New Year’s Eve Costume Ball.

NOW

The opera house offers space to hold meetings, conventions, retreats, and more. The grand hall auditorium occasionally hosts theater performances and musical acts.

WINNEMUCCA

THEN

In “The WPA Guide to 1930s Nevada,” it reads, “Winnemucca stages an annual rodeo (first week in September) for which bucking horses and wild range steers are brought in and to which riders come from long distances, attracted by generous cash prizes.”

NOW

Some aspects of Winnemucca remain the same as they did in earlier days. Visitors today can enjoy restaurants, museums, parks, a golf course, and more.

HELEN STEWART RANCH

THEN

Helen J. Stewart—known as the first lady of Las Vegas—operated a ranch in the Las Vegas Valley with the help of her father and others. The ranch sold goods to miners in the surrounding areas, and served as a waystation for travelers.

NOW

The area is now the Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort State Historic Park, and looks fairly different than it did more than 100 years ago.

Tonopah Army Air Field’s Unsung Heroes

HUNTING FOR REMNANTS OF WWII CRASH SITES PROVIDES A SOLEMN GLIMPSE OF HISTORY.

HUNTING FOR REMNANTS OF WWII CRASH SITES PROVIDES A SOLEMN GLIMPSE OF HISTORY.

STORY & PHOTOS BY DAVID FINNERN

The massive, four-engine B-24 bomber yawed slightly, as 1st Lt. Charles H. Enoch attempted a right turn to simulate a two-engine landing on the runway at the Tonopah Army Air Field. With the nose slightly upward, the plane banked left to right several times, then the left wing abruptly dropped on the last turn. The aircraft spastically yawed once again; this time the nose dipped as the right wing dropped dramatically. The nose and right wing tip hit the ground simultaneously, and the resultant explosion rocked the hangars and buildings surrounding the central Nevada air strip. All nine crewmen were killed instantly that Aug. 19, 1944. This particular B-24 crash occurred within one hour of another crash, which also ended the lives of its nine-man crew.

These incidents were an all-too-common occurrence during World War II at many airfields in America. Tonopah Army Air Field (TAAF) was just one of the installations created for the purpose of training pilots, navigators, bombardiers, and gunners for the dangerous task of aerial combat in the European and Pacific theatres. Unfortunately, training turned out to be just as lethal as combat.

All told, TAAF endured 58 serious crashes, scattered throughout the desert and mountains, and 134 aircrew lost their lives during its tenure as a training facility. These accidents primarily occurred in the long-range B-24 bombers and the P-39 Airacobra pursuit fighters, the mainstay of training aircraft at TAAF.

It’s estimated that 40 percent of pilot deaths during World War II were attributed to training accidents. According to the “Army Air Forces Statistical Digest,” 13,621 Army aircrew lost their lives in flight training and non-combatant incidents in the continental United States during the war. Almost 13,000 planes were lost in some 47,462 accidents. These figures are staggering, especially considering they represent Army personnel only. The Navy and the Marine Corps kept separate records.

SEEKING MORE THAN NUMBERS

Statistics are both cold and deceiving, however, and simply too easy to digest. I decided a visit to the actual sites was imperative to fully appreciate these incidents. Locating these sites could be challenging, but I found the answer: Allen Metscher, director of the Central Nevada Museum and president of the Central Nevada Historical Society. Allen has spent his adult life not only researching and locating TAAF crash sites, but interviewing pilots, aircrew, and workers who were stationed in Tonopah. He has authored numerous stories and books on the subject for no other reason than to keep alive the memories of those lost airmen. I contacted Allen via the Central Nevada Museum in Tonopah. He graciously agreed to draw a map to some of the crash sites.

My son-in-law, Keith Carney, luckily has the tools and toys needed for desert exploration. We loaded Keith’s camper and trailer with everything from motorcycles and gas to an ATV, then we—Keith, my 13-year-old grandson Seth, his friend, Chase Hendricks, and I—left Southern California to begin our adventure.

We arrived at the Central Nevada Museum in Tonopah the next morning. The front parking lot of the museum is an eclectic collection of artifacts, representing everything from Tonopah’s mining history to its World War II connection. Conspicuously displayed around the perimeter of the lot is a memorial to those who died in TAAF crashes, with B-24 props, .50 caliber machine guns, landing gear with shredded tires, and a curious bomb with the remains of a wooden wing (we were to learn later this is a glide bomb, one of the secret experiments exercised at TAAF).

Allen greeted us, and he was exactly as anticipated. Sporting jeans, a plaid shirt, and a ball cap with a B-24 insignia, he was clearly comfortable digging at crash sites, addressing academics, or educating a journalist and his family. He guided us to an area of the museum devoted to TAAF in general and to the crash sites in particular.

Viewing the paraphernalia recovered from the crash sites, it was easy to envision the historical and mechanical side of the horrific crashes. However, the human factor soon superseded cold statistics—a dog tag that belonged to B-24 pilot 1st Lt. George R. Gilpin; a key and coins from the pocket of 2nd Lt. M.A. Brown; an aviator cap emblem worn by Wayne C. Hurst; and a pocket watch owned by B-24 pilot 1st Lt. Earl Jacobs. These men had been gone more than 70 years, cut down in their prime as they prepared to defend their country and loved ones.

HISTORY ON THE DESERT FLOOR

We left the museum with a new appreciation of their sacrifice, plus books and maps to guide us to the base and two crash sites.

The air field was relatively easy to locate. Two original stone columns still stand guard on either side of the main entrance. A sentry shack that once stood between the columns disappeared long ago. The camper creaked as we exited the highway and onto the original asphalt road leading onto the base. Foundations lined the road for miles, and rickety hangars could be seen in the distance. I tried to envision the vitality that occurred here 70 years ago when 6,000 individuals went about the business of preparing for war. Now, it was vacant, quiet, and solemn.

We followed Allen’s map, and the asphalt turned to dirt. As Allen had warned, we approached a washed-out section, steep and filled with sand. The camper could go no further.

We unloaded the ATV from the trailer, and following the map’s landmarks we neared the first site. “We have to be close,” Keith said, scanning the distance. “Probably need to get out and hike around to find the exact area.”

We climbed out of the ATV and wandered into the emptiness of the desert. It wasn’t long before we came across the first evidence of the crash. An oxygen canister, small shards of Plexiglas, and then countless small remnants of a once-mighty B-24 bomber lay scattered amongst the brush.

While we knew some of the larger pieces had been removed, it was surprising just how little of the huge craft remained. Equally amazing was the miniscule size of some of the individual pieces, no doubt due to the explosion that ripped the plane apart.

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator had a wingspan of 110 feet and its deep fuselage had a bomb capacity of 8,000 pounds. The aircraft was powered by four 1,200-horsepower Pratt and Whitney engines and was equipped with 11 .50-caliber machine guns in the nose, waist windows, tail, belly, and in a turret on top. Later models, such as the B-24J, were more than 67 feet long. The entire aircraft, in which aircrew Charles Enoch, John Davis, Johnnie Mundell, Thomas Brown, Donnie Riordan, Richard Stringer, Walter Von Schenk, Junnel Tank, and Robert Pariseau lost their lives, was reduced to a handful of plastic and metal debris scattered across the desert. It was indeed a somber realization.

The next crash site was a P-39 Airacobra. Piloted by 23-year-old Capt. Charles C. Johnson III, the cause of the crash is somewhat enigmatic. There were no witnesses; only a plume of smoke rising from the desert, about 5 miles east of TAAF on May 28, 1943.

The P-39 was one of the first production fighters to be built as a “weapons system.” Uniquely designed, the Allison engine was mounted in the fuselage’s center behind the pilot, allowing for the massive arsenal it carried in the nose. Although numerous variants were produced, it often carried a 37-millimeter cannon in the nose. Two .50-caliber machine guns were centered just above the cannon, and four .30-caliber machine guns were mounted in the wings. It could carry a 500-pound bomb.

This site was located only a few miles from the B-24 site, but with no apparent landmarks, it was a little more difficult to locate. Finally, we saw the glint of reflected sun smattering off the desert floor just west of the dirt road.

We drove until we saw a steel pipe with a small attached metal plate rising a few feet off the desert floor. Allen had placed markers at some of the sites, with the crash date and names of the crew.

Keith and I once again scoured the desert floor looking for telltale signs of the aircraft. Again, it was surprising just how many, yet how small the fragments were. But while the pieces were small, a story soon emerged: A gas line, hose clamps, control linkage, and scraps of aluminum, many of which had the original olive-colored paint, reflected the afternoon sun. For us, who represented the three generations subsequent to these men, it was difficult to comprehend the complete story that took place at Tonopah Army Air Field 70 years ago. But we could understand the sacrifice. A death during training is no less the tragedy, no less the loss, and certainly no less heroic than it is in combat. Rest in peace, gentlemen; you have not been forgotten.