Nevada Part IV: Into the New Century

March – April 2014

Nevada booms out of a depression, and women’s suffrage highlights a progressive movement in the state.

BY RON SOODALTER

From its earliest days as a part of Utah Territory, Nevada was known as a veritable mineral mecca. First gold, and then silver, were washed, gouged, and blasted out of Nevada’s rock, generating hundreds of millions of dollars. Its treasure made moguls of the intelligent and the lucky. It helped propel the Union’s victory during the Civil War and was at least partly responsible for Nevada’s fast track to statehood. A seemingly reliable pattern emerged early on; when one claim busted, another would boom, causing a mass migration of fortune hunters to the new strike, but no appreciable lessening of ore output. Nowhere was this trend more evident than the Comstock. For years, the fabulous Virginia City-area strike yielded its riches, followed by a periodic bust, and then a rise from the proverbial ashes. It seemed that Nevada’s glittering bounty was limitless. Its citizens viewed any depletion in the state’s output as only a temporary inconvenience—a conviction validated by the next discovery…and the next.

THE DEPRESSION OF 1880-1900

Then came the Depression of 1880, and with it, the bitter realization that Nevadans had relied entirely on mining for their economic well-being. The decline of the mining industry presaged a two-decade dry spell. Over the next 20 years, there would be a number of attempts to regain financial stability, all of them doomed to failure. The most immediate and time-proven step, and one that had always worked in the past, was to search for a new, untapped source of mineral wealth.

The results were universally disappointing, and the focus shifted to a re-examination of promising sites that had been explored in the previous two decades, such as Austin, Tuscarora, Pioche, and Candelaria. Again, this proved a false hope. Perhaps most disappointing of all was Eureka, touted by many as the new Comstock. The promising boomtown had yielded an impressive $30 million in ore during the 1870s, but in the ’90s produced less than $2.5 million.

What initially promised to be a significant gold strike was made in Delamar, Lincoln County, in 1891. Although it provided a temporary boost, generating around $9 million in the last five years of the century, it was not sufficient to stabilize the state’s economy. It was becoming painfully apparent that this time mining would not provide an immediate solution to Nevada’s fiscal woes.

The disappointing results in the mines caused many Nevadans’ thinking to turn to other possible resources. The most obvious was agriculture—including the breeding of horses, sheep, and cattle— as a potential means of revitalizing the economy. There was certainly enough grazing land, provided sufficient water could be made available to accommodate an increase in livestock. The timing, however, could not have been worse. By the early 1880s, the fluctuation in the price per head of stock dropped well below the levels needed to rescue the state. Hoping to compensate for the shortfall by a dramatic growth in herd size, and realizing this would be impossible without more water, stock growers looked to irrigation as their only salvation.

Water reclamation was certainly not a new topic. Lack of water had plagued the residents of Nevada since prehistoric times, and over the centuries had inspired various crude systems of irrigation. The equation was simple: Without water, crops and animals would perish. None of this seemed to matter much while the mines were booming; but by the 1880s, the need for alternate forms of commerce had gone from desirable to essential, with agriculture heading the list.

In 1889, the state legislature passed two related laws that addressed the water issue. The first confirmed the public ownership of the unclaimed water from natural springs, and permitting its use for irrigation. The second law created the Board of Reclamation and Internal Improvements, with the authority to establish districts within the state to oversee the building of canals and reservoirs.

In Washington D.C., at the urging of Nevada Senator William Stewart, Congress formed the Senate Committee on Irrigation, whose members toured the West’s dry states in 1889, and held fact-finding hearings in their major cities, including Carson City. From a joint meeting of the Senate Committee on Irrigation and the Board of Reclamation came a report virtually begging for federal assistance for Nevada: “Can the [government] refuse to render assistance or will it allow one of its sovereign states to languish?”

Unfortunately, the act that had created the Board of Reclamation and Internal Improvements was repealed two years later. Nevadans made repeated attempts to initiate water reclamation projects, and held a series of irrigation congresses, but to no avail. By the beginning of the new century, it had become clear that agriculture and husbandry were not the answers to Nevada’s problems.

THE SILVER ISSUE

As Nevada’s citizens struggled through the last two decades of the 19th century, an issue of national significance imposed additional strain, and—as one of the country’s major silver-producing states— Nevada played a significant role. In 1837, Congress established a standard fixing the official ratio of silver to gold at 16-to-1; by law, 16 ounces of silver would be the equivalent of an ounce of gold. At the time, and for years after, it was understood that nearly all the silver mined in the nation would be sold to the government. However, with relatively little silver being mined through the Civil War years, the selling price rose dramatically, and the mining interests began seeking higher profits by selling their silver privately.

As Nevada’s citizens struggled through the last two decades of the 19th century, an issue of national significance imposed additional strain, and—as one of the country’s major silver-producing states— Nevada played a significant role. In 1837, Congress established a standard fixing the official ratio of silver to gold at 16-to-1; by law, 16 ounces of silver would be the equivalent of an ounce of gold. At the time, and for years after, it was understood that nearly all the silver mined in the nation would be sold to the government. However, with relatively little silver being mined through the Civil War years, the selling price rose dramatically, and the mining interests began seeking higher profits by selling their silver privately.

Then, in 1873, Congress passed a controversial piece of legislation known as the Mint Act, or the Coinage Act. While its touted purpose was to revamp and stabilize the country’s monetary system, it emerged from Congress with no provision whatsoever for the coining of silver dollars. This removal of silver from the nation’s currency was designed specifically to increase the demand for—and the value of—gold, and to place the country exclusively on the gold standard.

The law also provided for the establishment of four national mints, one of them in Carson City. The men behind the act— which its detractors labeled the “Crime of ’73”—were roundly accused of self-interest and corruption, a reasonable assumption considering the Grant administration was among the most corrupt in the nation’s history. However, it is probable that the authors of the bill were merely trying to protect the country from an impending depreciation of silver.

Many of the senators from the silver- producing Western states, including Ne- vada, were ignorant of—and, to a large extent, indifferent to—the true nature of the bill and consequently failed to vote against it. Although their lack of resistance to the passage of the new law was attributed by Virginia City’s Territorial Enterprise of February 4, 1873, to “Senatorial stupidity,” in fairness—despite a nationwide depression—Nevada at this time was in good financial shape. The Comstock was producing at its highest rate in years, and there was enough silver coming out of the mines to quiet Nevadans’ concerns. However, by 1876, with silver selling at a market value that was dictated by supply and demand, the price dropped radically. Coincidentally, the passage of the Mint Act had coincided with a number of new silver discoveries, and as silver production increased, prices fell. Depreciation reached 21 percent by mid-1876, creating a furor in the silver-producing states—including Nevada. The “Silverites,” as advocates of a return to the old system were called, pointed to the Mint Act as the culprit—a gross oversimplification—and shouted for its repeal and the reinstatement of silver coinage as the cure-all.

The new law hurt another group as well—the farmers. It favored the creditors and hurt the debtors, and farmers were clearly in the latter class. Every year, in order to purchase their seed and equipment, they depended on the banks for loans—advances on what they hoped would be a bountiful harvest. However, as the nation experienced fiscal panics in the 1870s, ’80s, and ’90s, farm prices continued to drop, and farmers—suffering from deflation and overproduction—sank deeper into debt. They joined with the mining interests in their fight for a return to the old system.

Several attempts were made to repeal the law, and to put the nation back on a “double-coin” standard. Perhaps the most dramatic was the creation of a third political party—the Silver Party—which was born in Nevada, and whose candidates and policies handily carried the state, but not the nation. In a sense, the campaign for the “remonetization” of silver was very much a western battle—and a losing fight. As a sop to the mining interests, Congress passed two compromise measures, in 1878 and 1890, providing for the government purchase of silver in quantity and at prices above market value.

However, President Grover Cleveland— in response to the nationwide Panic of 1893—forced their veto. The old 16-to-1 ratio was a thing of the past. Its death knell was officially rung in 1900, with the passage of the Gold Standard Act, establishing gold as the sole standard for the nation’s currency. America was not alone; nearly every nation in the world—with the exception of China—had gone on the gold standard by this time. Although the bimetallic system was, for all intents and purposes, dead on the national level, it continued to resonate in Nevada politics for years to come.

NEW CENTURY, NEW HOPE

After struggling through the final dark decades of the 1800s, Nevada finally embarked on a period of prosperity. As if awaiting the coming of the new century to reveal itself, the first of a number of gold and silver strikes occurred in 1900, initiating a boom that would soon end the state’s fiscal woes.

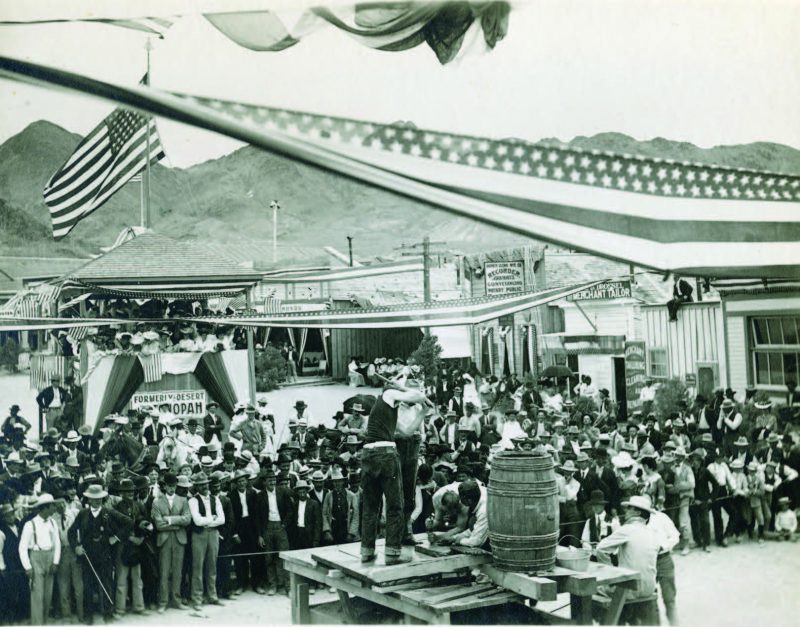

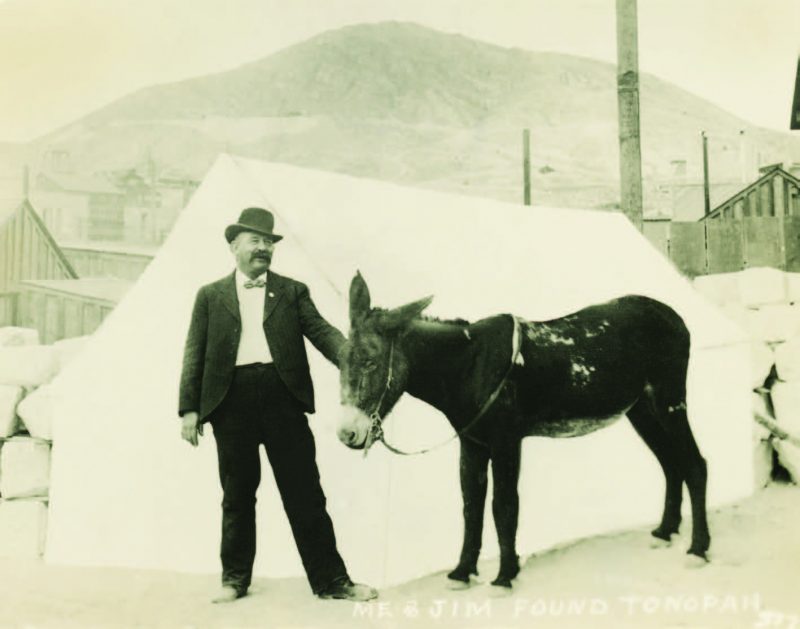

The finds were made the old-fashioned way—by prospectors leading their burdened burros across the remote moonscapes of Nevada. With the first strike, made in May 1900 by an enterprising miner named Jim Butler, the discovery of a promising outcropping soon gave rise to the fabulous Tonopah strike, and the resultant Tonopah Mining District. The area was so remote, however, that excavation and transportation were major issues.

With no timber or water readily available, Butler and his partners used picks and shovels to extract the first two tons of gold and silver, which they shipped north to Austin by freight wagon, and thence to Salt Lake City. Within a short time, more than 100 veins and deposits were found in Southern Nevada, with two particularly rich strikes rivaling Tonopah—Goldfield and Bullfrog.

Both were as inaccessible and difficult to mine as Tonopah and required major investments of capital to maximize the holdings. In December 1900, Butler—lacking the funds needed to fully develop his strike or to “prove up” on other likely locations—initiated a system of leasing. He and his partners would receive 25 percent of production after expenses, in exchange for allowing lessees to mine their holdings. This system proved highly successful.

Word spread, and soon a group of financiers from Philadelphia appeared on the scene. In July 1901, they paid Butler a third of a million dollars for his holdings, which they incorporated into the Tonopah Mining Company. In short order, the company controlled the entire Tonopah Mining District. In a series of developments that mirrored those at the Comstock decades earlier, they brought in milling and water companies to maximize production, and introduced banks to the new district.

The Eastern moneyed interests soon moved into other Nevada districts. The pattern in Tonopah had begun with leasing and soon developed into consolidation. It repeated itself in the Goldfield Mining District, which soon proved to be richer than anyone could have anticipated. One carload of ore alone, sent to the smelter in San Francisco, brought a return of nearly $600,000. In early 1907, Eastern investors incorporated the Goldfield Consolidated Mines Company and soon controlled all the Goldfield mines but one. For its part, the newly formed Bullfrog district saw its major company, Montgomery-Shoshone, purchased in 1905 by Charles Schwab, president of the U.S. Steel Corporation.

The corporate investors were masters of efficiency. In order to maximize their investments, they faced four major challenges: sufficient water, a reliable source of power, adequate capital, and transportation. They hired—and then purchased— private companies to find water and build supply systems that could handle the demand of the mills and mines. Power was provided by a number of small companies throughout the state, most of which were soon acquired by the Nevada-California Power Company. By 1912, the mega-outfit soon boasted three hydroelectric plants capable of putting out 16,500 horsepower, which they delivered to a number of mining sites, including Tonopah, Goldfield, Rhyolite, Beatty, Lida, Gold Center, and Manhattan.

The corporate investors were masters of efficiency. In order to maximize their investments, they faced four major challenges: sufficient water, a reliable source of power, adequate capital, and transportation. They hired—and then purchased— private companies to find water and build supply systems that could handle the demand of the mills and mines. Power was provided by a number of small companies throughout the state, most of which were soon acquired by the Nevada-California Power Company. By 1912, the mega-outfit soon boasted three hydroelectric plants capable of putting out 16,500 horsepower, which they delivered to a number of mining sites, including Tonopah, Goldfield, Rhyolite, Beatty, Lida, Gold Center, and Manhattan.

Sufficient water and power enabled the owners to develop the most efficient processing methods available. Through experimentation, they oversaw the construction of sophisticated milling systems, and within four years, they could claim an astounding average recovery rate of 93 percent and a cost that had dropped to an incredible low of $2.50 per ton.

Capital was never a problem for these eastern investors, leaving only one challenge to answer—transportation. Ultimately, the ore had to be conveyed to a railroad depot. The remoteness of the various strikes had initially dictated a system similar to that used in the early days of the Comstock: large freight wagons, drawn by teams of nearly two-dozen horses or mules.

A freight line was first established between Tonopah and Sodaville, and expanded into the other gold camps, including a line running from the Bullfrog to a small, unassuming town to the south—Las Vegas. Soon, however, the wagons, despite a 20-ton capacity, proved incapable of handling the growing demand of hauling goods, tools, machinery, lumber, and timber into the camps, and carrying the sacked tons of ore from the mines to the railroad. Clearly, what was required was a network of railroad lines.

The moneyed interests went into high gear and, beginning in 1903, soon had three major railroad lines connecting the gold camps to the outside world. The first two, the Goldfield line and the Tonopah line, merged in 1905 into the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad. Along with the Bullfrog and Goldfield Railroad, it soon tentacled out to Beatty, Las Vegas, Rhyolite, and a number of other camps. With the building of dedicated broad-gauge rail lines, all major challenges had been met and answered, and the gold and silver ore rolled from mine to destination efficiently and economically.

Meanwhile, the rapid “gentrification” of the larger camps paralleled that of the boom days of Virginia City, with fine restaurants, elegant hotels, theaters, and bordellos springing up in Tonopah and Goldfield. During the first decade of the century, a number of boomtowns could boast electric lights, water mains, telephones, newspapers, and schools.

Wild West legends Virgil and Wyatt Earp decided to try their fortunes in Nevada’s boomtowns. In 1905, Virgil—despite the fact that his left arm had been permanently crippled as a result of an earlier shotgun attack in Tombstone, Arizona—was hired as deputy sheriff for Esmeralda County, and assigned to Goldfield, where he also served as a “special officer” at the National Club, a high-end saloon. His reputation had preceded him; an article in the Tonopah Sun of February 5, 1905, referred to “Verge” as “one of the famous family of gunologists.” Virgil’s health was in decline, however, and he died of pneumonia that same year.

Wyatt moved to Tonopah in 1902, where he and a partner operated a saloon called the Northern, which advertised itself as “gentleman’s Resort” with “courteous mixologists and kind treatment to all patrons.” He also served as a deputy U.S. marshal, and as the head of a private police force, hired to “discourage” claim jumpers. Even in his 50s, the soft-spoken Wyatt enjoyed a reputation as a man “with the bark on,” as the saying went.

Ultimately, he left Tonopah to try his luck at prospecting, but the “big strike” was always over the next hill. As the mines continued to produce, Tonopah was named the seat of Nye County in 1905, and Goldfield of Esmeralda County in 1907. By the end of the first decade of the new century, a curiosity began to appear in the mining camps, as a symbol of status and progress: the automobile. Soon, prospectors were using it as a replacement for the burro. By 1913, cars were traveling over the road-less desert from camp to camp. The town fathers of both Goldfield and Tonopah, recognizing that the new horseless device presented a potential danger to the citizenry, established speed limits of six mph and four mph, respectively. Goldfield also passed an ordinance specifying “vehicles drawn by horse, at all times, have the right of way.”

Not everyone was content with the status quo, however. Inevitably, the monopolies’ control of all aspects of mining gave rise to worker abuses, and with them, a dramatic growth in organized labor. In 1905, the Western Federation of Miners, formed in the ’90s, merged with other groups to create the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)—the “Wobblies.” Difficulties were most prevalent in Goldfield, culminating in a November 1907 strike over the miners’ refusal to accept scrip instead of cash as a form of payment.

The mine owners wasted no time in contacting the governor, who approached President Teddy Roosevelt, who sent in federal troops to break the strike and neutralize the union. In January, the owners dropped the miners’ pay a dollar a day, and—using scabs who worked under the protection of the army—re-opened the mines. By March, at Roosevelt’s insistence, a state police force was formed to replace the soldiers. Left with no options, the union soon voted to return to work.

COPPER REIGNS SUPREME

The spate of new discoveries dramatically rescued Nevada from its economic slump. All that remained for continued fiscal stability was for the boomtowns to keep booming—which, as history had proven time and again, they could not. As with all strikes, the pattern of discovery, boom, and bust was predictable and unavoidable. It was simply a matter of time. All the trappings of elegance, the ambitious building projects, the pretensions of permanence, counted for nothing once the ore began to play out.

Bullfrog was the first major camp to decline, and its fall was precipitous, as was Goldfield’s. Tonopah, slower to rise than the others, had a much slower decline, and it still survives today aided by its halfway-point location between Las Vegas and Reno. Rhyolite fell fastest of all, in what one historian described as a “short but rapid journey into oblivion,” eventually leaving nothing but a few shells of buildings where there had once been a thriving community. Its 1908 population numbered 8,000; 12 years later, only 14 people remained.

However, just as the gold and silver output slowed, an unexpected development occurred that would once again place the state on solid footing. In 1900, a pair of enterprising young men named Dave Bartley and Edwin Gray entered White Pine County in the Robinson Mining District, staked two copper claims, and drilled a tunnel that soon revealed a tremendous strike. It had been no secret that copper could be found in Nevada; in fact, as early as the 1870s, low-grade copper ore had been discovered in White Pine County. But the lack of demand, combined with the difficulty of mining, shipping, and reducing it, made its extraction unfeasible. Now, however, demand had increased, and mining technology—as well as the prevalence of rail transportation—made the extraction of copper a highly attractive proposition. Admittedly, it would take years to perfect the methodology before the investment would pay off, but for those who knew what they were about, there were fortunes to be made.

In 1902, a Comstock engineer’s son, Mark Requa, paid $150,000 for the options on Bartley’s and Gray’s claim, which he dubbed the White Pine Copper Company. He soon bought up a neighboring claim and combined his holdings into the Ne- vada Consolidated Copper Company. Requa set about seeking investors whose capital would finance the building of a reduction plant, as well as the construction of the requisite railroad. He soon joined forces with the Guggenheim family of Philadelphia, which had been buying up large copper deposits around the globe. In 1906, they formed a jointly held new company, with the Guggenheims buying half-interest in Requa’s Nevada Northern Railroad.

Apparently, Requa was naive when it came to choosing his business partners. In short order, the Guggenheims edged Requa out altogether and proceeded to build an industry around the Gray-Bartley find. Ruthless though they might have been, the Guggenheims knew copper. By summer 1908, the reduction plant was completed, and the first copper shipped, after a massive capital outlay of more than $4 million. The investment, however, was more than warranted; within a year, production was at $6.5 million and climbing. As it increased year after year, production from the claim made the Robinson District the richest in the state’s history and would contribute to the fabulous wealth accumulated by the Guggenheim family. Decades later, when the Guggenheims hired Frank Lloyd Wright to construct the New York City art museum that bears their name, a disc was set into the floor at the entrance. It is made of copper and represents the ore type that endowed one of the world’s foremost repositories of modern art.

The mine was located a short distance from Ely, a faltering community that served as the seat of White Pine County. Although the copper boom initially promised to give Ely a new lease on life, the mine officials opted to build their own company towns, in order to maintain a more permanent workforce. As a result, four communities—Ruth, McGill, Veteran, and Kimberly—sprouted, initially taking on all the characteristics of typical boom- towns. Soon, however, their uniqueness became apparent. Building all the houses on the same pattern and in neatly ordered rows, the company controlled every aspect of government, business, and development. It acted as a benevolent landlord, renting the houses to the miners, and charging them for their coal, wood, and electricity—albeit at reasonable rates.

Residents received water, garbage collection, and police and fire services at no charge. They were provided with state-of-the-art hospitals, for which all residents paid a monthly fee. Emphasis was placed on clean living, with the towns’ activities limited largely to sports and dancing. For those residents wishing more visceral forms of entertainment, satellite communities—with such names as Ragdump, Smelterville, Riepetown, and Steptoe City—sprang up outside the perimeters of the company towns, offering women, saloons, and gambling.

Always with an eye toward saving money and enhancing profits, the Guggenheims began importing unskilled laborers from abroad—Greece, Britain, Japan, Serbia, and Austria—whom they paid lower wages than those paid to Americans for the same work. Relations between various ethnic groups among one another, and with the American miners already in place, were initially tense, and resulted in the company building separate communities along cultural lines. In time, however, the disparate groups assimilated through work, sports, social activities, and the schools.

Despite the company’s best efforts at labor management, inevitably there was occasional unrest. In 1912, a sympathy strike was staged in Ruth and McGill in protest over poor working conditions at a Guggenheim property in Utah. The recently formed state police—many of whom were simply gun thugs—were called in by management and, in the ensuing dust-up, killed two miners. The company settled the strike by granting the miners a small wage increase. There would be no more union actions until the end of the decade, when workers struck at virtually every Ne- vada mine in response to the post-World War I drop in metal production, and the widespread unemployment that resulted.

GOING PROGRESSIVE

As did the Comstock Strike decades earlier, the 20th-century boom introduced a new age of political life for Nevada. During the 1860s, the mining interests virtually ran the state, but not without the influence of California, on which they were economically dependent. This time, however, the mine owners were not reliant on California for their markets and supplies, having found Salt Lake City, as well as other cities to the east, more convenient. This time, the focus of the men who controlled the state would be exclusively on Nevada. And in the first two decades of the century, politics—reflecting what was going on in the nation at large—took a decided turn toward reform.

As did the Comstock Strike decades earlier, the 20th-century boom introduced a new age of political life for Nevada. During the 1860s, the mining interests virtually ran the state, but not without the influence of California, on which they were economically dependent. This time, however, the mine owners were not reliant on California for their markets and supplies, having found Salt Lake City, as well as other cities to the east, more convenient. This time, the focus of the men who controlled the state would be exclusively on Nevada. And in the first two decades of the century, politics—reflecting what was going on in the nation at large—took a decided turn toward reform.

This was largely the result of the efforts of politicians and statesmen of the stripe such as Francis G. Newlands. A politically ambitious former Mississippian, Newlands had gained prominence by championing the fights for free silver and irrigation. His stance was not purely altruistic, recognizing these to be the issues on which he could climb in order to achieve popular support for his political goals. But politician or not, he was a major force in bringing reform legislation, and in forwarding the cause of populism in the state. He became a staunch conservationist; not content with simply forwarding Nevada’s progressive agenda, as a U.S. senator he supported various national environmental causes.

In 1902, with the help (and political maneuvering) of President Roosevelt, Newlands sponsored the Newlands Reclamation Act, a federal law that funded irrigation projects in a number of Western states, and resulted in redeeming thousands of acres of Nevada’s desert, and creating two new communities, Fallon and Fernley. One political phenomenon of the early 20th century was the rise of the Socialist Party. Surprisingly, the first major foothold of Socialism in America was established in Nevada, beginning in 1906. Membership in the party quickly swelled, largely with working men. The strong-arm tactics employed at Goldfield and later at McGill, through the use of federal and state troops, convinced thousands of miners of the efficacy of joining the Socialist Party.

With support from many of the state’s Democrats, the Socialists’ popularity in the state gained increasing momentum right up to America’s involvement in World War I. By 1916, they had built their own colony, Nevada City, on reclaimed land in Churchill County. However, the party’s vehement anti-war philosophy, at a time when the nation’s sons were off fighting and dying in the fields of France, eventually turned off most of their supporters and rang the party’s death knell in the state.

Progressivism was sweeping the nation in the early 20th century, and Nevada passed its share of reforms on behalf of its citizens. As far back as 1885, Nevada legislators had pushed for the direct election of senators; their goal was finally achieved in 1913, with the passage of the 17th Amendment. At a time when labor issues were on the rise, Nevada also addressed the subject of labor legislation. In 1903 and 1908, laws were passed guaranteeing an eight-hour workday for specific jobs.

In 1909, the state created the position of mine inspector, to improve and safeguard conditions; and in 1911, a workers compensation law was enacted.

WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE

The history of Nevada’s efforts on behalf of progressive legislation and reform makes it hard to understand why the state was so consistently resistant to the concept of women’s suffrage. This is not to imply that the cause had no advocates. As early as 1869—the same year in which Wyoming passed a law allowing women to vote—the Honorable Curtis J. Hillyer, a Storey County legislator, introduced a resolution to a joint session of the Nevada State Legislature on behalf of women’s suffrage. His lengthy speech, of which this is a brief excerpt, was a masterwork of reason:

The history of Nevada’s efforts on behalf of progressive legislation and reform makes it hard to understand why the state was so consistently resistant to the concept of women’s suffrage. This is not to imply that the cause had no advocates. As early as 1869—the same year in which Wyoming passed a law allowing women to vote—the Honorable Curtis J. Hillyer, a Storey County legislator, introduced a resolution to a joint session of the Nevada State Legislature on behalf of women’s suffrage. His lengthy speech, of which this is a brief excerpt, was a masterwork of reason:

“The women of our land are human beings. They are, I presume, intelligent human beings. Moreover, sir, they are citizens of the United States. They are subject in every respect to the laws of the United States. Their lives and their fortunes are held and secured under the conditions imposed by those laws….Shall we continue to live in and breathe the foul vapors of this political dungeon, or shall we open the portals and bid enter, with women, the sweet light and pure air?”

The resolution passed both houses. However, by the next session of the legislature two years later, the bill mysteriously disappeared, never to surface again. To this day, no one knows what became of it. Further attempts to secure the vote for women were made in the legislature in 1883, 1885, 1887, and 1889, all in vain. In 1895, the legislature again passed a resolution amending the state constitution only to vote it down at their next session two years later.

Meanwhile, a women’s suffrage convention was held, and such luminaries as Emma Smith DeVoe and Susan B. Anthony visited the state. Mrs. C. B. Norcross, mother of State Supreme Court Chief Justice F.H. Norcross and a brilliant woman in her own right, had one of her pieces printed in the Reno Gazette of 1897. It read, in part: “the Creator never intended woman to take a subordinate place on this planet earth, for He gave to her the power to decide the physical and mental capacity of the human race in its pre-natal life… This old belief in the divine right of kings to rule nations and the divine right of men to rule women is a relic of barbarism… For one-half of the nation to make all the laws for the government of the whole can never be just to the other half.”

The bill was defeated again in 1897, after which surprisingly little was done to further the cause until 1911, when a professor, Jeanne E. Weir, established and helmed the Nevada Equal Franchise Society. She and Anne Martin, the society’s next president, campaigned vigorously throughout the state. In 1912, Governor Tasker Oddie advocated suffrage for women in his biennial address. Again a resolution passed the legislature, as a growing army of suffragists lobbied both lawmakers and voters for support. Two years later, the resolution passed both houses for the requisite second time. The bill was signed by Governor Oddie and placed on the ballot for the upcoming elections. All that remained was for the voters to ratify the law.

In the four months before the election, the pro-suffrage advocates stepped up their campaign among the voters, while those opposed brought in prominent nationally known anti-suffragists to squash the measure. Finally, in 1914—after a 45-year-long struggle—Nevada approved the amendment by a vote of nearly 11,000 to 7,258. The victory had been long and arduous. When the law passed, it did so five years before the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which gave all American women the right to vote.

Read the Entire 8-Part Series

Part I: The Unknown Territory

Part II: From Strikes to Statehood

Part III: Twain, Trains, & The Pony Express

Part IV: Into the New Century

Part V: War, Whiskey, and Wild Times!

Part VI: Gambling, Gold and Government Projects

Part VII: To War and Beyond

Part VIII: Looking Forward, Looking Back