Lincoln Highway

March – April 2013

The Lincoln Highway in Nevada

A CENTURY LATER, YOU CAN STILL ROAD TRIP ON THE “MAIN STREET ACROSS AMERICA.”

BY P. GROVER CLEVELAND

I’ve traveled stretches of dirt road nearly untouched since the early days of the last century, and yet they’re still perfectly drivable. I’ve camped where folks crossing the country in their overloaded Model T Fords once spent the night. I’ve seen ranches and stage stops that have been here for 150 years. Away from the pavement, at times I’ve felt like I’ve returned to the early 1900s and am seeing the country for the first time.

I’ve traveled stretches of dirt road nearly untouched since the early days of the last century, and yet they’re still perfectly drivable. I’ve camped where folks crossing the country in their overloaded Model T Fords once spent the night. I’ve seen ranches and stage stops that have been here for 150 years. Away from the pavement, at times I’ve felt like I’ve returned to the early 1900s and am seeing the country for the first time.

I’ve traveled the Lincoln Highway, and you can, too.

The Birth of the Lincoln Highway

At the time of its dedication in 1913, the Lincoln Highway—dedicated to the memory of Abraham Lincoln—was little more than a line on a map describing a route from New York City to San Francisco. It was to be “the first coast-to-coast rock highway,” and promoters hoped to have it finished in time for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (world”s fair), held in San Francisco throughout much of 1915.

Travel between Western towns at that time was an adventure of mud, ruts, washouts, and even no roads at all. There were no road maps west of the Mississippi; however, automobile ownership in the U.S. was rising, and the Good Roads Movement was still going strong. America was on the move.

A Track Across the Desert

In part, the early Lincoln Highway followed the route of the 1860 Pony Express mail route and the Overland Stage. In Nevada, that meant a succession of passes and valleys across rugged Great Basin topography. There were mining towns and ranches where one could find radiator water and, sometimes, gasoline. Travelers often camped out in the sagebrush or found lodging and meals with a friendly rancher.

In 1919, during the height of his military career, future president Dwight Eisenhower described the Lincoln Highway in Nevada when he accompanied an Army caravan from the White House to the West Coast: “From Orr”s Ranch, Utah, to Carson City, Nevada, the road is one succession of dust, ruts, pits, and holes. This stretch was not improved in any way, and consisted only of a track across the desert. At many points on the road, water is 20 miles distant, and parts of the road are 90 miles from the nearest railroad.” Eisenhower clearly was not impressed.

The poor condition of sections of the Lincoln Highway could be attributed to the fact that it was, for all intents and purposes, ahead of its time. The route was largely financed and promoted by businessmen such as Carl Fisher of Indianapolis, founder of Indianapolis Motor Speedway. He was supported by Henry Joy of the Packard Motor Car Company and others involved in the automobile manufacturing industry.

Private money was necessary because there was no funding for highways at the state or federal level. In Nevada, there wasn’t even a State Highway Department until 1917.

Lincoln Highway Remembered

As difficult as travelers might have found the Lincoln Highway to navigate in its early days, it helped pave the way, literally, for the modern highway and interstate system motorists practically take for granted 100 years later. The beauty of Nevada is that, if we allot ourselves the time, we still have the unique opportunity to escape the modern world and return to a slower-paced era.

The iconic Lincoln Highway that carried thousands of people westward is still here a century later, under U.S. Highway 50 in many places, or just alongside it in the sagebrush. In my many travels exploring the original “Main Street Across America,” I found there is much to be discovered just off “The Loneliest Road in America,” rarely more than a few miles from pavement. There are ghost towns, old ranches, and vistas beyond compare.

Driving the Old Lincoln Highway Today

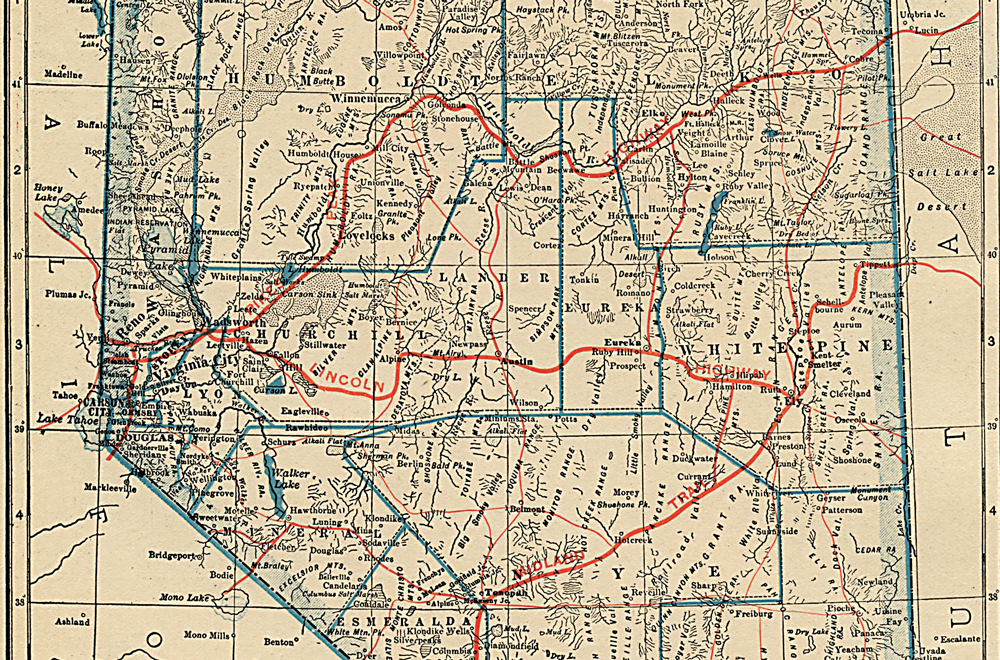

The Lincoln Highway originally entered Nevada in the east near Ibapah, Utah, crossing the Goshute Indian Reservation, over Schellbourne Pass and down to Ely. Then it turned westward following present-day Highway 50, more or less, through Hamilton, Eureka, Austin, and Fallon.

The western end then split into two routes: one leg, the Pioneer Route, went through Carson City past Lake Tahoe and ended up in Placerville, California. The other headed through the Truckee River Canyon from Wadsworth, passed through Sparks and Reno, and left the state at Verdi up the old Henness Pass Road to Truckee, then onto Sacramento where it met the Pioneer Route (Route 40, or Interstate 80 as we know it today, wasn”t built until many years later). The total length of the original Lincoln Highway was more than 3,000 miles from Times Square in New York City to Lincoln Park in San Francisco.

Over the years the Lincoln Highway was graded, widened, paved, re-routed, and, in Nevada, simply covered up by the construction of Highway 50. If all you want is a quick orientation, then driving 50 will do that…somewhat. But the real flavor of the old road will be lost. You need to get off the pavement, even for a few miles.

The back roads are generally fine in the summer, but muddy and not recommended in wet weather. Few of the roads I am going to describe require fourwheel drive. Travel with another vehicle if you can, or tell someone your itinerary and stick to the plan.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Lincoln Highway, but I fear the grand old road is fading from our collective memories. I want to remedy that. I urge you to get off the pavement for a while and experience a little of what traveling was like 100 years ago.

Our Nevada adventure starts at Fernley and ventures east.

Fernley

Farm District Road hasn”t changed much since its early days, and this is a pleasant diversion that will give you a good introduction to the Lincoln Highway, albeit paved. Turn off Highway 50 in east Fernley at the roundabout, and follow State Route 828 south, then east, to rejoin 50. The scenery is particularly pleasing in the fall when the leaves are turning.

Fallon Sink

The area between Fallon and Sand Pass is a sandy and often muddy flat that was difficult to cross until the road was improved in the 1920s. Today it is an easy crossing. As you approach Sand Mountain from the west, look to your left and you can see how the Lincoln Highway, then a primitive trail, skirted the flat.

Sand Springs Pass

Just east of Sand Mountain you can see the old highway to the north. You can drive on portions of it if you are careful. This section was paved sometime in the 1940s and is slowly deteriorating.

Frenchman

An important stop for travelers was this cafe-hotel-restaurant-service station, which is now just a wide spot off the side of the road in Frenchman Valley.

Middlegate

The old road passes in front of Middlegate Station, a popular bar and restaurant (Nevada Magazine dares you to take the Monster Burger challenge). Middlegate was a Pony Express stage stop long before the Lincoln Highway arrived.

State Route 722

For 11 years, the Lincoln Highway went through New Pass, which was a rough route. In 1924, this was abandoned in favor of a road known as Nevada Highway 2 that remained in use for 42 years until a new highway was constructed over New Pass and Cold Springs. I highly recommended this beautiful bypass, one of the best-preserved sections of the old road, between Middlegate and Austin.

To access S.R. 722, turn south off Highway 50 three miles past Middlegate. It passes by Eastgate over 7,452-foot Carroll Summit and down into Smith Creek Valley. Here you really begin to feel the openness of the Great Basin. Smith Creek Valley presents some amazing vistas on the way to Railroad Pass, 20 miles across the valley.

Austin

The highway we use today, which twists and winds its way above the central Nevada town, was constructed during the road-building frenzy of the early 1920s. The original highway went up the canyon at the east end of town. It is a pleasant drive in dry conditions.

Turn off Highway 50 at the east end of town onto the dirt road near the white water tank. At the summit, turn left to rejoin the modern highway.

Ford’s Defeat

Ford’s Defeat is so named because of the steep grades near the summit that overwhelmed early Model T Fords. This is a route that takes some serious path finding and is not well known (as a result, it remains a pristine segment of the old highway).

Instead, I recommend a slightly later version of the Lincoln Highway over Hickison Summit that served to bypass Ford’s Defeat. You will notice the road to your left as you approach the summit on Highway 50 from the west.

Instead, I recommend a slightly later version of the Lincoln Highway over Hickison Summit that served to bypass Ford’s Defeat. You will notice the road to your left as you approach the summit on Highway 50 from the west.

It is easier to access from the east. About a half-mile west of the road to Hickison Petroglyphs, turn north off the main highway. This is a dirt road that at first seems steep, but past the summit is well graded. This will lead you back to Highway 50 after about three miles.

Hamilton

Hamilton, once the seat of White Pine County, was a typical boom-and-bust mining town. A few of the old buildings are barely standing, and the Hamilton cemetery is a poignant reminder of the tough lives miners and their families led out here.

Thirty miles west of Ely is a sign for the Ibapah Recreation Area. Turn there, and continue straight for six miles. You will come to a Lincoln Highway landmark called White Pine Summit. The 1915 guidebook describes this point as, “2767 Miles from N.Y. 564 Miles to S.F. No accommodations. Beautiful view from the point.”

There are convenient markers placed by the Bureau of Land Management at the junction. Bear to the left. Although the road has been graded and widened in some places, you are on the original Lincoln Highway. The Hamilton ghost town site is at 8,000 feet, so be prepared for cold weather in the winter.

Ely and Robinson Canyon

West of Ely the highway shared a road in Robinson Canyon with the Nevada Northern Railway—the scene of many unfortunate vehicle-train collisions. The road was greatly improved in the 1920s.

In Ely, Aultman Street was the Lincoln Highway. The famous Hotel Nevada was not built until 1929, after the Lincoln Highway arrived in town.

Schellbourne Pass

By far the most extensive and beautiful journey you”ll take, in my estimation, is over the Schell Range north of Ely. This was part of the route from Salt Lake City around the southern end of the Salt Lake Desert that entered Nevada just west of Ibapah. You can take this trip north out of Ely and end up at West Wendover; it will add about an hour to the journey.

This is an isolated trip in some of the most scenic basin and range topography you will find. East of Schellbourne Pass there are only two ranches, one of which is abandoned. The road is well graded for the most part, but there are no services and no cellphone reception. Be prepared, but don”t be afraid of trying this fabulous trip. Start with a full tank of gas and a good spare tire.

Tippetts Ranch

Take Highway 93 north out of Ely through McGill and about 35 miles north, turn right at the rest stop onto White Pine County Road 893. You will pass Schellbourne Ranch, Anderson Ranch, Stone House, Tippetts Pass, Tippett, and Tippetts Ranch.

Tippetts Ranch has been in operation for more than 100 years. Even today you might run across a roundup, as I did last year. The ranch is located in the Antelope Valley, close to the Utah border.

Continue northeast through the Goshute Indian Reservation to Ibapah. From Ibapah continue north to rejoin Alternate 93, 25 miles south of Wendover. In its infancy, Nevada”s Lincoln Highway was often no more than a collection of ranch roads, dirt tracks, and wishful thinking. My adventures have opened my eyes to the difficulty of automobile travel in the West a century ago. I’ve acquired a deep appreciation for the troubles our forebears encountered in coming to the West. I hope you will, too.

RENO TO FERNLEY

Take the path most traveled.

For a more “urban” Lincoln Highway experience consider the trek from Fernley to Reno to the Nevada-California border (or vice versa), which is a combination of Interstate 80 and city streets and was once known as the northern Donner Route. Look for these landmarks:

- Wadsworth — small town and gateway to Pyramid Lake was an original Lincoln Highway stop

- Sparks — 15th Street & Prater Way (travel west on Prater and look for period motels and buildings)

- Reno — California Building at 75 Cowan Dr. (built in 1927 for an exposition commemorating the completion of the Transcontinental Highway)

- Reno — National Automobile Museum (enjoy Bill Harrah’s classic car collection)

- Reno — Fourth Street

- Verdi — appreciate the historic bridges over the Truckee River

There’s also the southern Pioneer Route, which follows U.S. Highway 50 southwest to Carson City, then to Zephyr Cove and around the scenic south shore of Lake Tahoe.

Time Travel

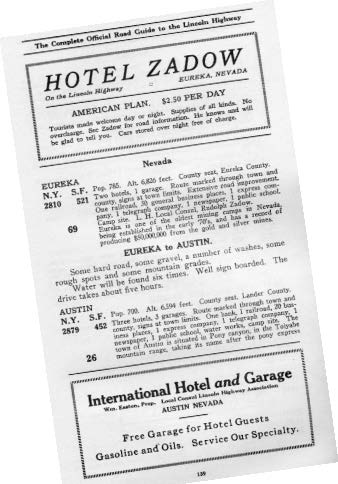

The Complete Official Road Guide to the Lincoln Highway (1915) advised travelers as to the necessities. Here are some examples from the guide:

- One Lincoln Highway radiator emblem

- One set of tools

One pair of good-cutting pliers

One pair of good-cutting pliers- One hand axe

- One medium shovel

- One gallon of auto oil

- One Auto-Robe trunk

- Two sets of tire chains

- Two extra tire casings

- Two jacks

- Three spark plugs

- Eight feet of high-tension wire

- Upper and lower radiator hoses

- Spare light bulbs

- Towing rope

The list is pages long and includes sage advice such as “don’t wear good shoes” and “don’t forget the colored goggles.”

The author wishes to thank the Churchill County Museum, Austin Museum, White Pine County Museum, and the Special Collections of the University of Michigan for their kind permission to use the historic photographs considered for this story.