Transitory Train Towns

July – August 2018

Transitory Train Towns

NEW RAIL ROUTES OFTEN LEFT OLD TOWNS OUT TO DRY.

BY ERIC CACHINERO

It is generally well known that train-sized holes were drilled through hundreds of yards of solid rock to lay railroad tracks during the construction of the Central Pacific Railroad. In fact, throughout Donner Pass, countless tons of rock were blasted and cleared to create a series of tunnel systems that would give life to the burgeoning west.

But in what may be a lesser-known method of railroad construction, in the early 1900s—just some 35 miles east of Donner Pass in the swamplands east of Reno—land was carted in and laid down, not blasted away. During the course of six months in 1903, the Southern Pacific

Railroad Company used 334 railcars to spread 65,000 carloads of gravel, rock, and dirt, raising the land’s elevation by an average of 18 inches.

The new swamp town would go by several names (East Reno, Glendale, and Harriman) after its creation, but none would stick harder and longer than the city we all know today: Sparks.

Sparks is testament to the fact that the railroad was king, even when it meant having to uproot entire well-established communities, buildings and all, and move them just because a better railroad path was built.

In those days, if your town was cut off from its railroad connection, you could bet it would bust faster than funding from fool’s gold.

WHAT IS SPARKS WORTH?

Sparks—though nameless in those days—seemingly rose from the swamps overnight. The Southern Pacific shortened and straightened its lines across the Forty Mile Desert in 1902, choking the town of Wadsworth nearly out of existence.

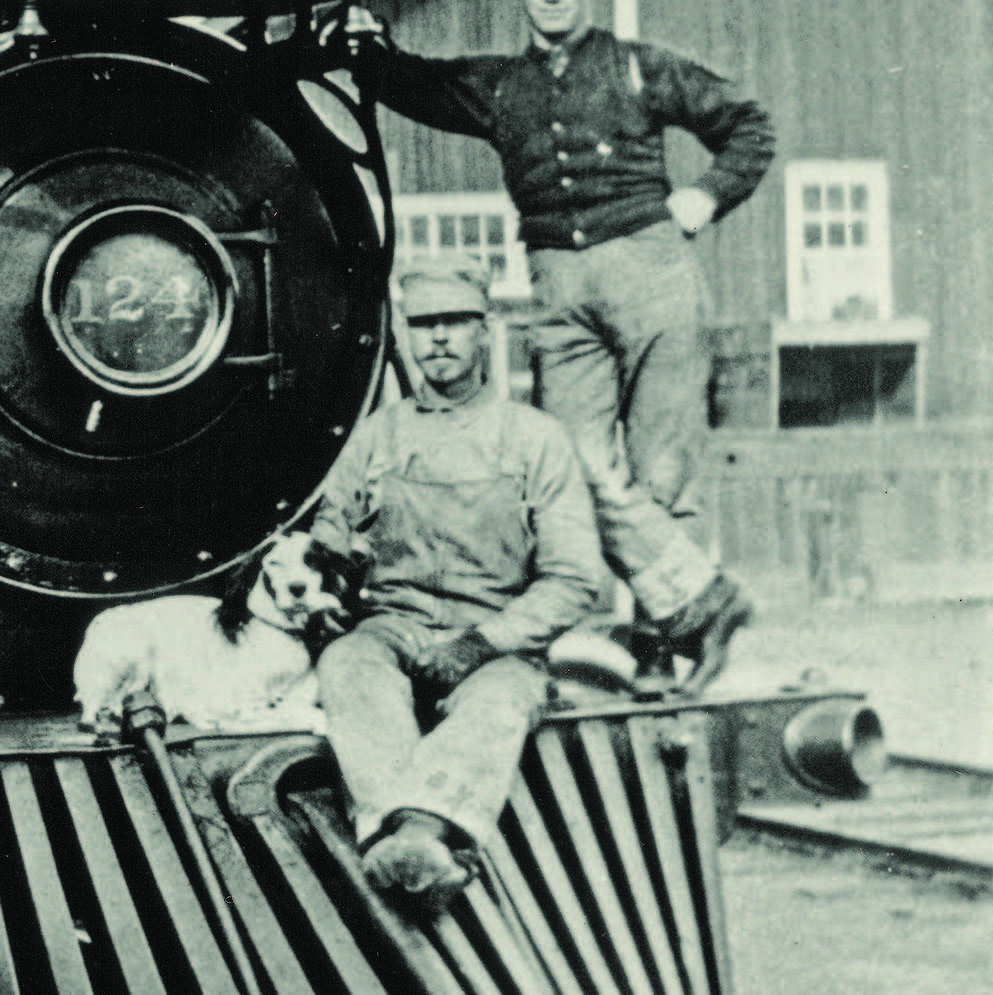

Prior to the route change, Wadsworth had acted as the railroad’s division point—where crew changes and locomotive repairs took place, among other things. But the new route skipped the town completely, and instead created the need for a new division point somewhere in the Truckee Meadows. Rather than shell out the cash for Reno’s high real-estate costs, the railroad simply built its own town atop the swamps just east of Reno.

Construction took place from 1903-1904, with the railway roundhouse and facilities built first. The 40-stall roundhouse was the largest in the world at the time of its construction, and according to the Sparks Museum and Cultural Center, was the largest building west of the Mississippi. A tract of land just north of the roundhouse was reserved for railroad workers, many of whom had moved from the shrinking town of Wadsworth.

But the livelihood and resources of Wadsworth didn’t simply shrivel up and fade away. Employees and citizens of the railroad town had no choice but to follow their jobs to the new division point in Sparks, so they simply packed up the entire town and sent it on down the line. In July 1904, personal belongings, trees, shrubs, buildings, livestock, and more were placed atop railcars and sent to their new home. In some cases the Southern Pacific even offered free transportation of entire homes, which were cut into sections and reassembled at their new location.

The population of Wadsworth in 1900 was 1,309, and in 1910 had dropped all the way to 250, according to the Nevada State Archives.

The new town still lacked a name in early 1905. After failing to name the town New Wadsworth, East Reno, Glendale, or Harriman (after Southern Pacific Railroad president Edward H. Harriman), a suggestion was thrown out to name the town after Nevada Governor John Sparks. The name stuck, and Sparks was incorporated on March 15, 1905.

HEYDAY TO NULL

The town of Dayton would come to suffer a similar fate to that of Wadsworth, though it was the loss of profits in the world’s richest silver district, not the booming commerce of the transcontinental railroad that spurred the series of events.

The profits of The Comstock Lode dwindled severely by the 1880s. Dayton suffered majorly by the mines’ decline with the population dropping to less than 500 by 1880 (down from around 2,500 people in 1865). An article in the “Nevada State Journal” read: “Dayton… has sadly shrunken from its former prosperity, the business portion of it, burnt up several years ago [in 1866 and again in 1870], not having since been wholly rebuilt.” Then came the railroad.

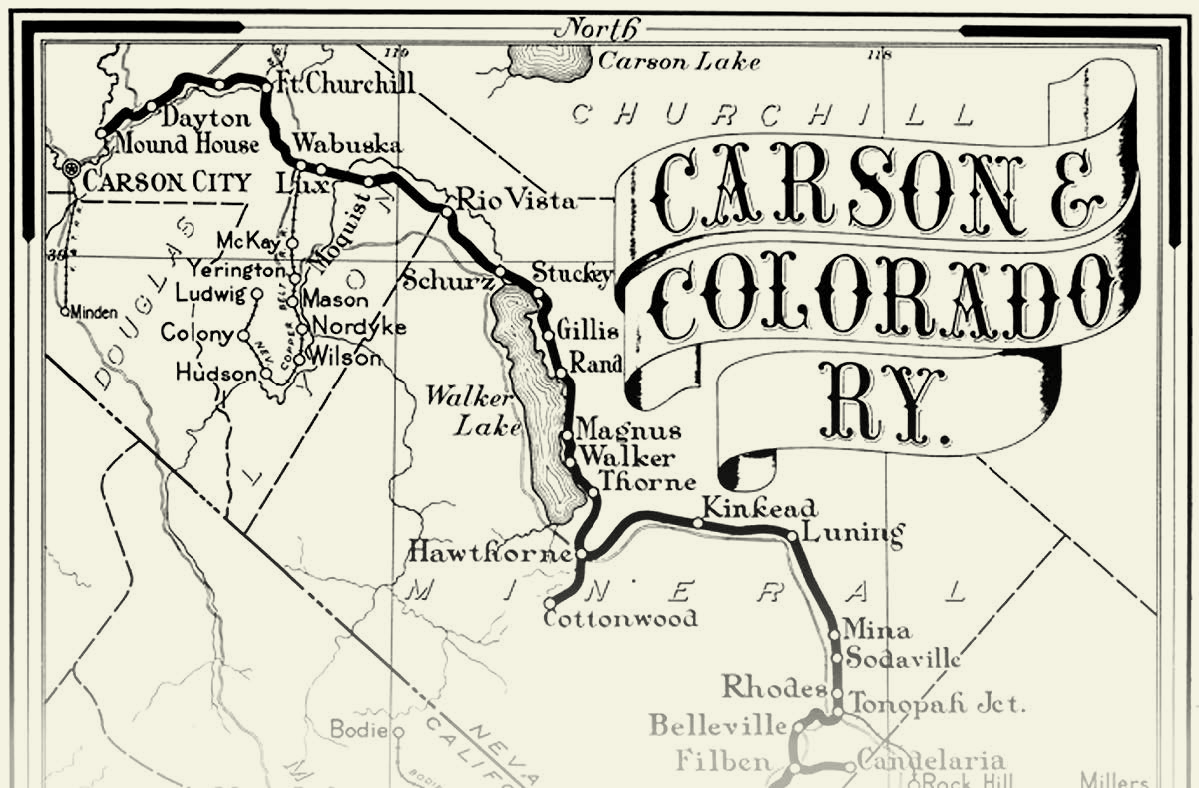

According to Dr. Linda Clements of the Historical Society of Dayton Valley, “The Carson & Colorado Railroad was started in 1880 by the surviving members of the ‘Bank Crowd,’ including most of the same men who built the Virginia & Truckee.” The Bank Crowd had the mills to support a new Comstock Lode, they just needed access to the ore. As a mining railroad, the Carson & Colorado connected many of the mines in central Nevada and southeastern California and supplemented them with new profiting mines that were popping up in the deserts to the south.

On May 10, 1880, the narrow-gauge Carson & Colorado Railroad was incorporated, running 293 miles from Mound House all the way to Keeler, California, below the Cerro Gordo Mines. The railroad was originally supposed to run all the way to the Colorado River (hence the name) but it ran west instead of south, and never ended up reaching the southern tip of the state.

The Bank Crowd’s plan worked, bringing life back to Dayton and initially bringing profits back to the shareholders. Unfortunately for them, though, the wealth was short-lived. In 1900, the Carson & Colorado was losing money and was sold to the Southern Pacific Railroad for $2.75 million. That very same year, silver was discovered in Tonopah, sparking a boom that helped the Southern Pacific make its investment back in one year.

Then in 1905, the Hazen cutoff essentially left Dayton in the dust as far as railway traffic goes. The cutoff ran from Churchill County to Mound House, tapping the Carson & Colorado into the Transcontinental line. As Linda puts it, “Dayton was on a little-used cul-de-sac of a rail.” Once the cutoff opened, Dayton saw one train a day, then three trains a week, and eventually one a week. The deathblow came in June 1932, when the Southern Pacific requested discontinuance of rail traffic between Wabuska and Mound House. On April 23, 1934, the Dayton depot closed forever, and the rails were removed in 1936. Though Dayton lived on, its status as a booming railroad town died.

LIFE WITHOUT RAILS

Neither Wadsworth nor Dayton ever truly became ghost towns; in fact, they still have populations of several hundred and several thousand, respectively. But it is interesting to wonder what would have happened had the railroads not abandoned them.

Instead of Las Vegas, would the world talk about taking a weekend gambling trip to Wadsworth, with first-class dining and luxurious hotels? Would Dayton be the largest metropolis in the state, with booming business prospects and colossal strip malls? Probably not. But because history went the way it did, and the rails left the towns, we can certainly wonder.