A Bullish Bout you’d Barely Believe

January – February 2017

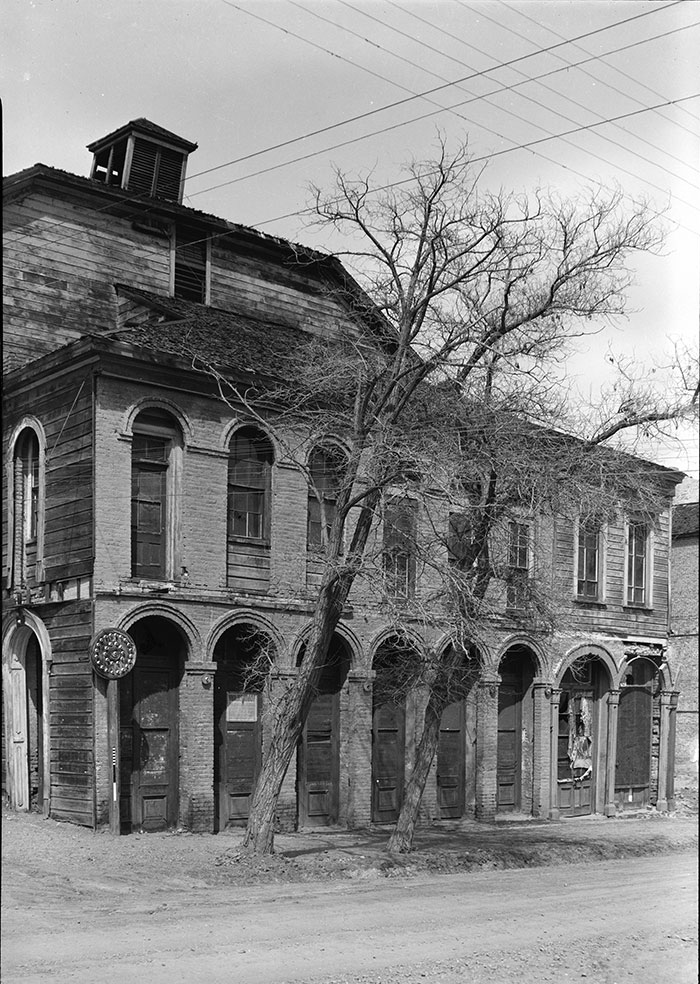

Piper’s Opera House hosted a bizarre brawl that pitted two unlikely opponents.

BY DANNY DEMERS

In the 19th century, fights that pitted bears and bulls were a popular spectator sport. The strangest venue for such an event occurred in 1871 in Virginia City. The fight, held inside Piper’s Opera House, was the only such event ever held indoors. Unlike today, opera houses were general-use halls, which handled a wide variety of entertainment. Live entertainment was the only kind—there were no radios, televisions, movie theaters, or Internet. At the time Virginia City was the largest city in the state of Nevada, hosting a population of 20,000 engaged in exploiting the Comstock Lode. A mining town, its people worked hard and played hard. One eyewitness described 1870s Virginia City as a town full of “saloons…glittering with their gaudy bars and fancy glasses, and many-colored liquors, [where] thirsty men are swilling burning poison. Organ grinders are grinding their organs and torturing their consumptive monkeys; hurdy-gurdy girls are singing bacchanalian songs in bacchanalian dens. All is life, excitement, avarice, lust, devilry, and enterprise.”

IN THIS CORNER

Montana’s New Northwest newspaper, commenting on the upcoming Virginia City spectacle, asserted that it “would be the first time in the history of civilization that such entertainment was ever presented on the boards of an opera house.” The article described the bear as being 700 pounds and noted that neither animal would be chained. The cage was made of “inch [thick] bars of iron placed 4 inches apart and standing 16 feet high.”

The event took place one evening in early September in the theater, which was described by nationwide newspaper accounts as being completely packed. The opera house had a seating capacity of 1,600. Newspapermen reported the bruin cowered in one corner of the cage while “the fierce looking bull…made a dash at the bear, [giving] him…a tremendous dig with his horns, causing the bear to utter a loud roar…the bear clawed the bull about the head for a second or two and then got away.” The bull made a second charge that resembled the original. On the third charge, the bear “for a short time, made lively use of both teeth and claws, showing more fight than at any time in the evening…the bear [then] went off into another corner of the cage.” The bull stood and snorted for a monotonous 10 minutes before making another dash “jamming the bear against the side of the cage…[to which] the bear clawed a little, uttered a roar, and lurked away to another corner.”

The paying crowd wasn’t happy. It became necessary to “stir the animals up…[to foster] a rush by the bull and a roar or two by the bear.” In desperation, “a red cloth was fastened to a pole and waved about the bear [to force the bull to charge out],” but to no avail. The bear simply laid down and the promoters “punched him with sticks, whipped [him] with foils, and prodded him with iron bars…making him roar and strike at those who were tormenting him…[another] got on top of the den…to the clamorous cries [of the crowd] to stir up the bull with a pole.”

Instead of being stirred up, the bull charged the bars of the cage “causing [it] to shake, and bending one of the large bars until quite a gap was made.” Instantly there was a stampede of theatergoers. As the bull pulled back, a theater employee fired at him with a rifle. One of the bullets ricocheted off the bars, hitting another employee—neither the bull nor employee were hurt seriously. The remaining crowd, thinking it wise to leave the bull alone, confined “the business of stirring up…to the bear [only].” Once it became apparent the bear wouldn’t get up, Charley Palmer, the promoter, declared the bear was almost dead and the fight was over.

Instead of being stirred up, the bull charged the bars of the cage “causing [it] to shake, and bending one of the large bars until quite a gap was made.” Instantly there was a stampede of theatergoers. As the bull pulled back, a theater employee fired at him with a rifle. One of the bullets ricocheted off the bars, hitting another employee—neither the bull nor employee were hurt seriously. The remaining crowd, thinking it wise to leave the bull alone, confined “the business of stirring up…to the bear [only].” Once it became apparent the bear wouldn’t get up, Charley Palmer, the promoter, declared the bear was almost dead and the fight was over.

TECHNICAL DECISION

Palmer’s comments enraged the already boisterous crowd: “An immense hooting followed…an uproar of voices…[the crowd] was fearfully angry and awfully dissatisfied…[demanding] the fight go on,” according to a newspaper story. The gaslights were dimmed to encourage patrons to vacate the building. More than 100 patrons stormed the stage and threw chairs and whatever else they could get hold of against the cage to rile up the animals. Theater engineers turned the gaslights off, immersing the opera house in total darkness. Patrons “lit matches and yelled fiercely for the house to be lighted.” Acceding to the unruly patrons’ cries, the lights were turned back on. Palmer, amid hisses and hoots, told the crowd he had done all he could do. This prompted several theatergoers to again jump onto the stage and with knives attached to poles, they began stabbing the animals. Fireworks were thrown on the stage but just before being ignited a stagehand cautioned burn down the building and warned the bear and bull might get out and stampede into the theater.

DOWN AND OUT

Tired, the crowd, according to the Memphis Public Ledger, finally “dispersed quite satisfied” that there was nothing more they could do to make the animals fight it out to the end.

Bear-bull fights gradually lost popularity as society’s attitudes and sensitivities were changed by civic associations, which condemned such events as cruel and inhumane. The last bear-bull fight in the United States was held in Laredo, Texas in 1895.