A Mysterious Murder On The Comstock

January – February 2017

VIRGINIA CITY – A MYSTERIOUS MURDER ON THE COMSTOCK

Unanswered questions loom after the murder of a notorious prostitute.

BY ROBIN FLINCHUM

It’s been 150 years since that dreadful January morning when Mary Jane Minieri left her little cottage on Virginia City’s D Street and stepped carefully through the mud to her friend and neighbor Julia Bulette’s back door. She could have never imagined that she was about to walk into the beginning of one of the most enduring stories in Nevada history.

LEGEND AND LORE

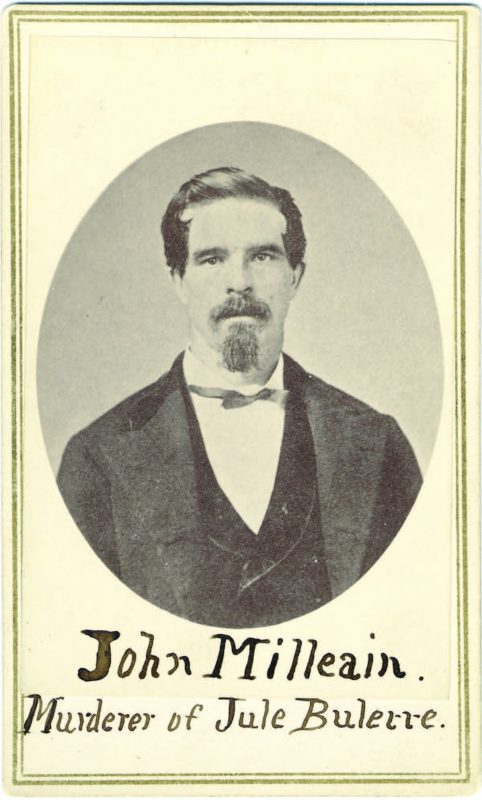

She would find that Bulette, an independent prostitute, had been beaten and strangled to death in her bed and that much of her sumptuous wardrobe, including silks, furs, and jewelry, had been carried off in the dark of night. Almost a year and a half later, a French immigrant day laborer would hang for the crime in front of a crowd of thousands. But did John Millain really kill Julia Bulette? The answer, all this time later, isn’t entirely clear.

COLD CASE

The murder shocked Virginia City. In January 1867, the town was only 8 years old. The city had seen its share of killings and its residents generally accepted brawling and dueling as a part of life. But the Bulette murder—perpetrated on a sleeping woman in her nightgown—was different. After Alf Doten, a reporter for the Territorial Enterprise newspaper, had been to the little cottage to see Julia’s mangled body, he wrote in his diary “Worst murder ever in this city—horrible.”

Doten, who had known Julia in her professional capacity, estimated that she was about 35 years old. She had been a prostitute for more than 15 years and had achieved modest success. While she was often segregated from ‘respectable’ women, she had many friends among her peers. As an honorary member of the Virginia Fire Engine Co. No. 1, she had also earned some admiration in the larger community. The Territorial Enterprise eulogized her as “being of a very kind-hearted, liberal, benevolent, and charitable disposition, few of her class had more true friends.”

In the days following the murder, her friends wanted justice. To complicate matters, some feared that Bulette’s death was only one in a string of similar killings. Virginia City police had been consulted in 1863 and again in 1864 in connection with the unsolved murders of two prostitutes in San Francisco. In each case the woman was in her mid-thirties or older, approaching retirement or at least having worked long enough to accumulate some wealth. Each woman worked independently, lived alone, and was killed late at night, apparently after she had retired to bed. And each woman had some connection to Virginia City.

The San Francisco murders had been shockingly bloody, the victims repeatedly stabbed. The Bulette murder had been done with less gore, but in all other respects the killings shared eerie similarities. In a pre-Jack the Ripper world, this left reporters, police, and other prostitutes grappling with an unthinkable idea.

The Bulette murder also had larger implications for Virginia City, because mining production was on the decline that year and the local economy was in recession. For those invested in the city’s future, it was vitally important to keep up civic pride and investor morale.

A LEAD

Despite their best efforts, however, it would take Virginia City police nearly four months to capture a viable suspect. In early May, another independent prostitute awoke to find a dark figure skulking about her room and later identified him as 37-year-old John Millain (sometimes spelled Milleain).

“It is not at all improbable that the same man who so foully murdered Bulette attempted to murder and rob [Martha] Camp last night,” reported the Virginia Daily Trespass.

Most everyone believed the murderer had been caught. “The man is either a perfect friend or he is scandalously belied by those who have some knowledge of his past history,” said the Enterprise, adding that Millain was rumored to have once had a pretty wife in San Francisco who died mysteriously. It was even reported that he had confessed to the Bulette murder, though Millain denied this.

The Sacramento Daily Union claimed “The detectives have learned that Millain was driving a water cart in [San Francisco], on a route in the worst part of town, at the time that the prostitutes were mysteriously murdered.”

“This creates deep excitement in this city,” wrote Doten in his diary, “he will hang.”

However, guilty as many believed him to be, the police had yet to prove it. Millain remained in custody on a charge of attempted robbery while they searched for clues. In late May, a woman named Mrs. Cazentre came forward and said she’d recently bought a length of silk from him under suspicious circumstances. By the end of the day, the silk had been established as a unique piece purchased by Julia Bulette before her death. In the next few days, more shopkeepers came forward with stolen items they had unwittingly purchased from Millain. Then police were alerted to a house where Millain had stored a trunk filled with the rest of Bulette’s missing treasures. From that moment forward, John Millain was on a fast track to the gallows.

THE PROSECUTION

The city needed someone to pay, not only to maintain the morale of its investors and economy, but to keep the civic peace. Friends of Bulette’s, never specifically identified in court documents but possibly members of the Virginia Fire Engine Co., among others, asserted that Millain would hang one way or another.

Judge Richard Rising, who had been presiding over the District Court since its establishment some years before, and who had seen the results of vigilante justice in action, hoped to maintain order. He would later write that during those days “many outrages and crimes…were constantly being committed in this city and to endeavor to create a terror upon evildoers, I imposed…very severe punishments.”

The trial lasted only one day, with not a single witness for the defense. Millain’s grasp of the language was poor, despite some 15 years in American mining camps. He was uneducated and he did not present well. After a brief deliberation, the jury handed down a guilty verdict.

“The bell of [Virginia Fire Engine Co.] No. 1 pealed out in notes of joy,” wrote Doten privately. “This is the first instance I ever knew of the public rejoicing over such a verdict, where a man’s life is at stake.”

But the Daily Trespass explained it thus; “That John Millain is the cruelest and most heartless murderer of the age is beyond doubt… that he has been a professional strangler there is but little doubt, and his last confession will doubtless elucidate the terrible doubts that have shrouded several murders in California with impenetrable mystery.”

On July 5, in front of a crowded courtroom, John Millain was sentenced to hang and accepted the verdict with quiet composure. But was he guilty?

THE DEFENSE

Millain maintained his innocence, admitting only that he had drunk a bottle of wine and fallen asleep under Julia’s house while two other men went inside. They had afterward given him the trunk full of jewels, silks, and furs to hold for them and he hadn’t known until the next day what really happened. The two men, whose names he said were Douglass and Dillon, had long since disappeared. The trial evidence was entirely circumstantial and consisted of testimony proving that Millain was in possession of Julia’s stolen belongings and that he had sold many of them, thereby profiting from her death.

The lawyer appointed to defend Millain was apolitically ambitious young man named Charles DeLong, well liked in Virginia City until the trial put him in the unenviable position of defending the town’s most hated villain. He asked for a change of venue but was denied. On appeal, the Nevada Supreme Court upheld this decision on the grounds that, because Julia Bulette was a prostitute, her friends had no influence on public opinion and a change of venue was unnecessary. During the trial DeLong questioned Mrs. Cazen- tre about the silk dress fabric she had purchased from Millain. He prompted her to tell the story of the first time she met John Millain, when he came into her tobacco shop to hide from police after he’d been brawling with a prostitute known as Buffalo Joe. This story, of no con- ceivable value to the defense, could have established in the minds of the jurors that Mil- lain had a history of violence against women.

In the end, DeLong’s best strategy was to argue that the evidence only showed Millain to be a fool, rather than a killer. But the jurymen believed him to be a killer and DeLong could not prove otherwise.

The conviction was upheld on appeal and the execution was set for April 24, 1868. On the gallows, in front of a crowd of between 3-5,000, Millain was serene and thanked the priest and nuns who had given him comfort in his last days. In French, he criticized DeLong, the Virginia City police, and the prostitutes who had testified against him.

STRING HIM UP

What he didn’t do, to the disappointment of many, was admit to either the Bulette murder or any of the others he was suspected of committing. He did not explic- itly deny his guilt but spoke with sincerity of being ready for God’s judgment, which he expected to be less harsh than that of his fellow man. Former Territorial Enterprise reporter Mark Twain was on hand to witness the execution.

“I believed that if ever it would be possible to see a man hanged, and derive satisfaction from the spectacle, this was the time,” Twain wrote. “For John Melanie [sic] was no common murderer…He was a heartless assassin.” But the lack of a real confession left doubts. In 1873, The Sacramento Record ran a brief item claiming that the “mystery attached to the [Bulette] murder…will shortly be cleared up.” The reporter seemed sure that a prisoner in custody there was about to be linked to the crime, though nothing further came of it.

While Millain was in jail awaiting sen- tence, another pros- titute was attacked in Virginia City by a skulking late-night prowler who was never caught. In the dozen or so years after Millain’s execution, at least two similar unsolved prostitute mur- ders were committed in California mining camps. Were they connected? Did John Millain kill Julia Bulette? And only Julia Bulette? Or was he merely a dupe in the wrong place at the wrong time?

Only Millain knew the answers and he took them with him when he stepped off the gallows and into the abyss all those many years ago.