The Metropolis That Wasn’t

January – February 2014

THE METROPOLIS THAT WASN’T

North of Wells lies one of Nevada’s more intriguing ghost towns, with zero ties to the state’s mining past.

BY GREG MCFARLANE

Many of Nevada’s ghost towns boomed, prospered, and faded in the 1800s, when the state was largely undeveloped and had no major population centers. It’s hard to believe that a city that existed in the 1940s—an era of jet engines and color television— has all but vanished.

Many of Nevada’s ghost towns boomed, prospered, and faded in the 1800s, when the state was largely undeveloped and had no major population centers. It’s hard to believe that a city that existed in the 1940s—an era of jet engines and color television— has all but vanished.

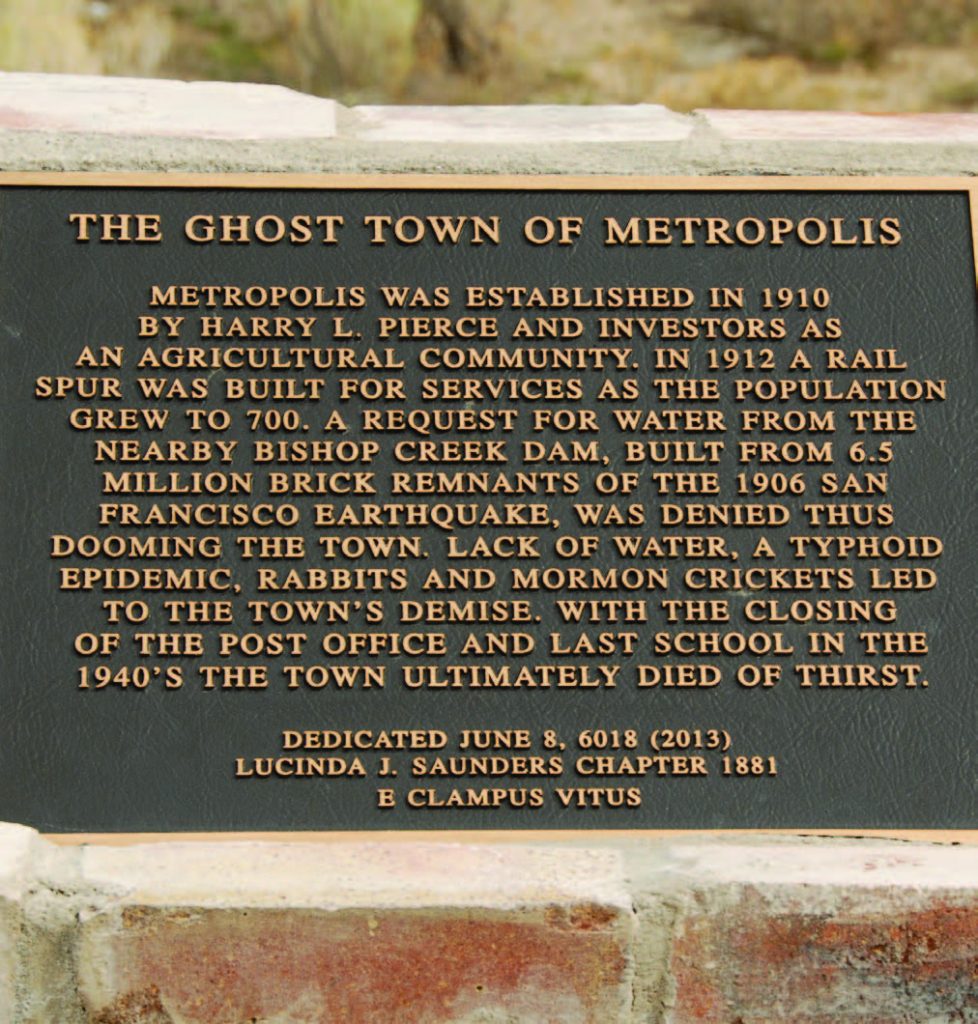

Metropolis ghost town, north of Wells in central Elko County, is distinctive in other ways, too. Unlike Candelaria, Delamar, Rhyolite, and every other Nevada ghost town, the grandiloquently named Metropolis was never a mining center. Rather, its reason for being was equal parts farming, proselytism, and hope.

Similar to present-day Hadley in Nye County, Metropolis was a company town. It was founded in 1910 by the Pacific Reclamation Company of New York, which envisioned a layout in which 7,500 people could live in harmony, supporting themselves by growing wheat in a region grossly unsuitable for doing so. Pacific Reclamation’s ambitious plan for Metropolis included a central business district, amusement hall, and other amenities. The Southern Pacific Railroad even built a spur from Wells, in hopes of transporting more goods and passengers. However, the local climate had other plans.

In the 1930s, Metropolis was ravaged by plagues straight out of the Book of Exodus. First, jackrabbits arrived and devoured the crops. Next was typhoid—sanitation on the remote flats not as advanced as it is today. That was followed by a wholesale invasion of millions of Mormon crickets, Nevada’s unofficial state pest. Then came a devastating fire, which burned down the town’s hotel in 1936.

Worse than any of those, and ultimately proving fatal to Metropolis, was relentless drought. The survival of a farming community is contingent on access to water, and Metropolis could never find a consistent source to sustain its population. The closest approximation of such a source, Bishop Creek, is a tributary of the Humboldt River. The Pacific Reclamation Company attempted to harness the creek’s power by constructing an earthen rockfill dam seven miles east of Metropolis, along with a diversion canal. Interestingly, the dam was built from brick remnants of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

Due to a protracted water-rights dispute with the downstream town of Lovelock (more than 200 miles away), the area available for irrigation dwindled. Dryland farming is difficult enough with modern conservation and rotation methods, but in 1930s Metropolis it was essentially impossible. As for the dam itself, it still stands and impounds a small reservoir but hasn’t been maintained since the mid-1980s.

Census records of the time are spotty, often attributing a city’s population to the encompassing county. But an educated guess is that Metropolis’s population maxed out at around 2,000 in the 1920s. That’s slightly less than modern-day Tonopah and slightly more than Caliente.

Stately in its decrepitude, at one time Metropolis boasted all the trappings and features of a modern, self-contained American town: multiple schools, a lumberyard, and a church to serve the town’s overwhelmingly Mormon population. Time and neglect have since combined to erase almost every trace of Metropolis, with two notable exceptions.

The Lincoln School—erected in 1919—is the most conspicuous site in Metropolis today. The school is visible for miles, which has less to do with its size than with its prominence on an otherwise flat, empty landscape. Most of what remains of the brick structure is its tall entrance arch, which continues to carry some weight of the wall above it while the upper floors lay in ruins.

When visiting Metropolis, proceed with caution and pay close attention. The school’s basement is accessible via concrete stairs, enticing day explorers into its depths. What they’ll find is a mass of ruins and some colorful graffiti. Much of the ground floor has yet to collapse, although it’s pockmarked with treacherous holes large enough for an adult to fall through to the basement below. The rest of the floor seems somewhat solid; an impromptu field test demonstrated that it could easily hold a foolhardy 200-pound photographer/writer on assignment for Nevada Magazine.

When visiting Metropolis, proceed with caution and pay close attention. The school’s basement is accessible via concrete stairs, enticing day explorers into its depths. What they’ll find is a mass of ruins and some colorful graffiti. Much of the ground floor has yet to collapse, although it’s pockmarked with treacherous holes large enough for an adult to fall through to the basement below. The rest of the floor seems somewhat solid; an impromptu field test demonstrated that it could easily hold a foolhardy 200-pound photographer/writer on assignment for Nevada Magazine.

One block east of the school is its lone counterpart that completes the civic “skyline.” Hotel Metropolis once stood three stories high, but now there’s nothing left of it save a foundation and a block. Without the benefit of records and old photographs, it’s difficult to tell that dozens of guests used to spend the night here. Many of them undoubtedly wondered how they’d ended up in untamed rural Nevada and how a town with so majestic a name could look so unassuming.

Befitting a ghost town, the graveyard is one part of Metropolis that sees a good bit of activity. However, it’s also easy for a visitor unfamiliar with the area to miss. Valley View Cemetery is immediately southwest of town, sitting behind a cattle gate, which is closed with a carabiner but unlocked. While a rear-wheel-drive passenger car can easily make the trek from pavement to Metropolis, the short drive past the cattle gate can be treacherous for even a high-clearance vehicle, especially when wet. It’s better to park, get out, and walk the few hundred feet.

The cemetery contains the names of several generations of pioneer families—Bake, Hammond, Hepworth, Hyde, and Uhlig—with some interments as recent as the mid-2000s. Many of the families’ descendants ranch in the vicinity and will one day be laid to rest beside their ancestors in this serene and starkly quiet locale.

Most days, the intermittent moos of distant cows are the only sounds to break the silence at Metropolis. Plinkers, geocachers, off -roaders, and those armed with metal detectors typically have the place to themselves. Eight decades past its prime, Metropolis continues to fascinate and inspire.

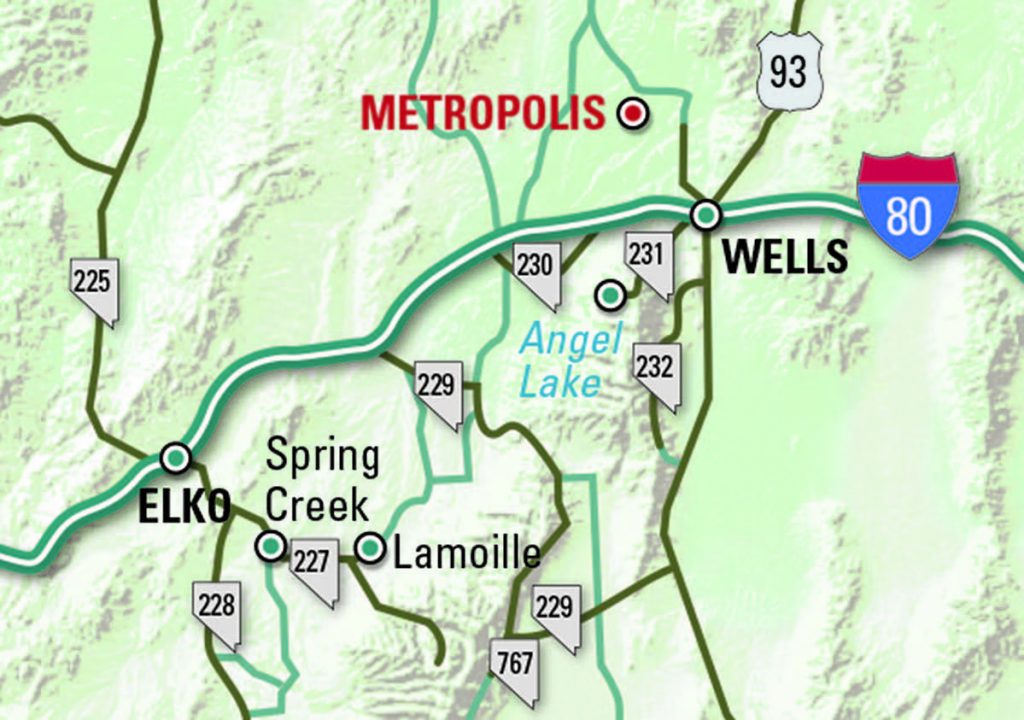

HOW TO GET TO METROPOLIS

Start in Wells at Exit 352 off Interstate 80. One block north is 6th Street. Turn left on 6th. One mile later, turn right on Lake Avenue. Once you’re over the train tracks, turn left on 8th Street, which becomes County Road 754. This road is paved. After 12.5 miles, the pavement ends. Half a mile beyond that, turn left (south) at Botts Homestead. From there it’s 1.8 miles to Metropolis.

Start in Wells at Exit 352 off Interstate 80. One block north is 6th Street. Turn left on 6th. One mile later, turn right on Lake Avenue. Once you’re over the train tracks, turn left on 8th Street, which becomes County Road 754. This road is paved. After 12.5 miles, the pavement ends. Half a mile beyond that, turn left (south) at Botts Homestead. From there it’s 1.8 miles to Metropolis.

Rather than retrace your route, return to Wells by continuing for another 5.7 miles past several ranches. The dirt road is well maintained, but unmarked, and eventually meets up with County Road 754.