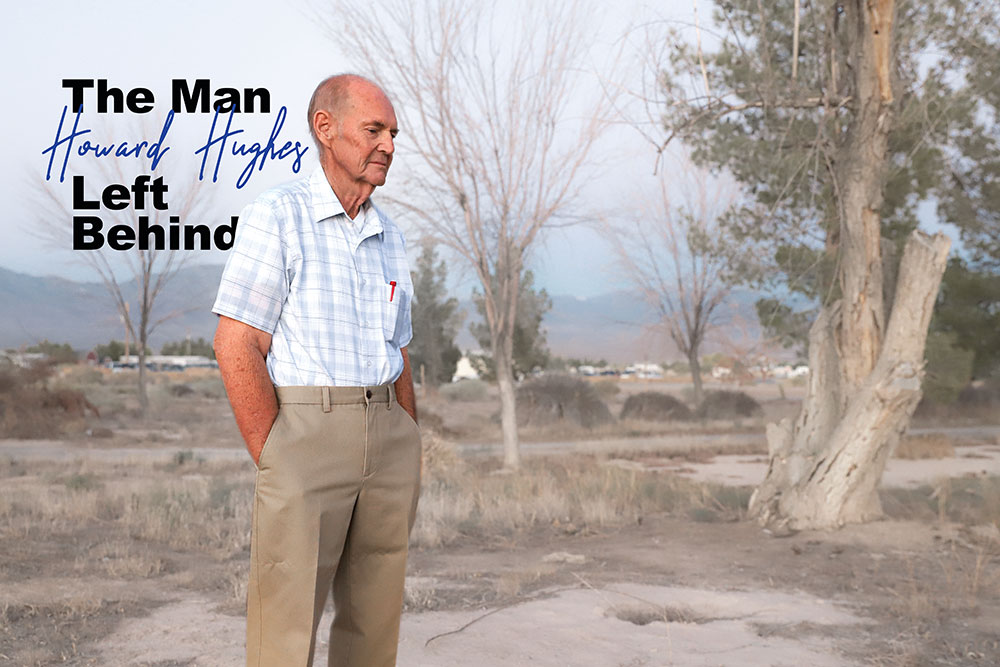

The Man Howard Hughes Left Behind

November – December 2018

Melvin Dummar recounts his brush with fortune and loss.

Melvin Dummar recounts his brush with fortune and loss.

BY SHAUN ASTOR

“I grew up in Fallon. There was an airport, where the Churchill County rodeo grounds are at,” Melvin Dummar, now 74 years old, recalls on a warm evening as the sun falls behind the Resting Spring Mountain Range to the west of his home in Pahrump. “I was 6, 7 years old, it was still open, and I would watch the planes. I wanted to fly.”

From its mining to the casinos that make up a portion of the state’s tapestry, Nevada’s past has been guided by the oscillations between boom and bust. Wealth can be made and lost at the flip of a card, the spin of a wheel, or the swing of a shovel. It may appear at a moment and disappear just as quickly.

This is the story of one man’s brush with fate that made history and almost destroyed his life.

GAMES OF CHANCE

On a December night in 1967, Melvin Dummar, a 23-year- old country-and-western songwriter and former Air Force serviceman living in Gabbs was driving through the central Nevada desert. In the midst of a separation with his wife who had left for southern California, Dummar had decided to drive to the neighboring state in a attempt to reconcile with his ex-wife.

“It was payday, I had to wait around until 3 or 4 in the afternoon when the paychecks came out. They wouldn’t cash checks in Gabbs, they didn’t have any banks. I used to like to gamble, it’s a vice I had. So I got to Tonopah and I went into the Mizpah Hotel and cashed my check. I sat there for two, three, four hours. I was about even.”

To hear Dummar recall the night is to hear someone describe an event they have run through their mind thousands of times. With a meticulous attention to detail refined by courtroom examination and media skepticism, Dummar describes the events that unfolded that night.

“I took off toward Vegas. I had a 1966 Chevrolet Caprice. It was around midnight I passed the Cottontail Ranch.”

The Cottontail was a brothel located along a desolate stretch of Highway 95, about 15 miles south of Goldfield. Feeling tired, Dummar pulled off the highway to make a quick bathroom stop down an empty dirt road.

“I hadn’t gone too far; a hundred, maybe a couple hundred yards, and that’s where I found him,” Dummar says of the man that would change his life. “He was laying right in the middle of that dirt road.”

Startled, Dummar was about to drive to Goldfield to alert the sheriff when the body moved. The National Weather Service would list that night’s temperature as being in the 20s.

“I helped him up and I put him in the car. He had a beard and long hair, and had a big knot up on the side of his head,” Dummar remembers. “The whole side of his face was bloody. He was just trembling and shaking. He was about frozen to death. He was dressed like a bum, I thought he was an old prospector or wino.”

Dummar asked the man if he needed to go to the hospital or sheriff.

“The only thing I could get out of him for the first half hour was, ‘No, I want to go to Vegas.’”

Dummar drove the shivering stranger south.

“I had no idea who he was; all I could see was somebody in need. I sang him a song I wrote. I remember exactly what I sang to him:

You can rise from a beggar to a king

With hard work, faith, and courage you can conquer anything

For once upon a time they said man would never fly But now you don’t even look as a jet goes streaking by”

“I think that I was almost in Beatty when he finally stopped trembling and shaking. Then he started asking me all kinds of questions. I told him when I got out of the service I tried to get a job in the aircraft industry. I went to Douglas Aircraft and they wouldn’t hire me. I tried to go to Hughes Aircraft, and they wanted me to have an engineering degree. That’s when he said, ‘If you need a job, I can arrange it. I’m Howard Hughes.’”

“Sure you are…” Dummar thought to himself, and he just kept driving.

“I got him into Vegas,” Dummar continues. “He said, ‘Can you take me to the Sands Hotel?’ When I pulled into the parking right in front, he panicked. He wanted to go around back.”

Dummar took the man to a small building a short distance behind the casino. While getting out of the car, the man asked Dummar if he had any money.

“I thought, he’s a bum, maybe he wants to buy a bottle of wine or make a phone call or whatever. I reached into my pocket and gave him the change I had. He thanked me, and I drove off.”

“I never heard from him again.”

ACT TWO

Fast forward to 1973, and Dummar has married his second wife, Bonnie. The two live in a small Utah town named Willard, about 50 miles north of Salt Lake City, where they owned and ran a gas and service station.

“It was 1976, I was there at the desk,” Dummar recalls. “I was going to college studying real estate, but I used to take every class that sounded interesting to me, even if it wasn’t real estate. I took aviation ground school; I took flying lessons so I could fly an airplane.”

“I don’t know what I was studying, but I was reading. It was a couple weeks after Hughes had passed away. A guy walked in and started talking to me.”

A man named LaVane Forsythe would later come forward admitting his work as a courier for Howard Hughes, including that Hughes had presented him a handwritten will in 1972 to be given to Melvin Dummar following his death.

Dummar recounts the visit.

“He asked me questions like, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if somebody like you was left in Hughes’ will?’ And I was like, that would be nice, everyone’s talking about it. But that’s not gonna happen. I had another customer come in. I told him, excuse me, it was a lady and I went out and I filled up her car with gas. When I came back in, the guy was gone. I didn’t even see him leave. I went back over and I had one of my books, and right in the middle of that book was an envelope, addressed to David O.

McKay [president of the Church of Latter-Day Saints (LDS), who had passed away in 1970], and it was signed Howard Hughes.”

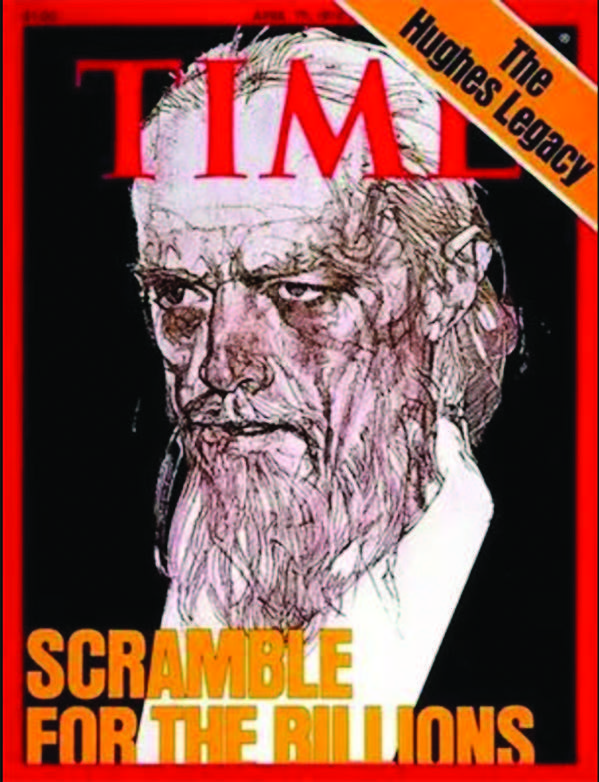

Inside the envelope was a handwritten will signed by Hughes granting 1/16th of his wealth to Dummar. Hughes’ assets included vast land and mine holdings, as well as Hughes Aircraft and the Summa Corporation. Though valuations of his holdings and wealth were believed to have been underreported, current estimates have placed Hughes’ worth upon his death at $2 billion (over $11 billion when adjusted for inflation).

“I remember taking out the envelope and reading it, and putting it back, and taking it out and reading it. I don’t remember how many times I did that,” Dummar says. “What I thought is someone was pulling a joke on me, but I didn’t know who and I didn’t know why. Who knew that I’d even met him? I’d told a few people about it shortly after it happened, but it’d been nine years. And what flashed through my mind is if this is true, there’s no way on God’s green earth I’m ever going to see a penny of it. And that’s exactly what happened.”

The will became known as The Mormon Will and set off a series of lawsuits and appeals that would try to discredit it as a forgery. Dummar was said to be the mastermind behind the fraudulent document. Further complicating things was the fact the envelope was addressed to the deceased president of the Mormon Church.

Dummar would deliver it to the top floor of the Mormon Church headquarters in Salt Lake City, the closest he was able to come the Mormon Church’s president’s office given the security outside of his office.

“A couple of days [after dropping off the envelope], when the news media got ahold of it, it was some mysterious woman who delivered the will to the Mormon Church,” brings up Dummar, citing what would be one of a stream of inaccuracies that plagued media coverage surrounding the Mormon Will and the ensuing trial.

A Nevada jury ultimately ruled the Mormon Will a fake in 1978.

A SHOCKING AFTERMATH

“I was paranoid for a long time because of people threatening me because I wouldn’t share with them,” Dummar describes the fallout from jury’s decision, despite the ruling against him and the Mormon Will.

“I was paranoid for a long time because of people threatening me because I wouldn’t share with them,” Dummar describes the fallout from jury’s decision, despite the ruling against him and the Mormon Will.

“People told me they were going to shoot me, or blow up my car.”

“I must have had 100 different people say they were with me and I had to give them half. Some of them would come after me with knives. As much as I love music and performing, I think it was probably 20 years I wouldn’t listen to the radio. I wouldn’t give interviews and I wouldn’t talk to reporters. Some reporters wanted to interview me and I’d say, ‘Just go make something up, that’s what you do anyway.’”

Dummar recounts the inaccuracy of the media reports surrounding the story and his personal details.

“Sometimes I’d read an article and I wouldn’t even know what they were talking about. Then I’d see my name in there. I was where? I did what? I was with who? It’s all a figment of some writer’s imagination,” he says.

Dummar explains how it wasn’t just him suffering from the courtroom smear campaign against him. In an effort to convince the jury that the will was forged, those close to him were hurt as well.

“I’m LDS, and I was going to church quite often and in the Elders Quorum. And a lot of the so-called good LDS people turned their backs on us because of stuff that was in the paper. They thought I was a crook, a forger, and a thief…just lie after lie after lie. They wouldn’t even let their kids play with ours. I got so irritated. It turned into a nightmare for us.”

His portrayal in court as the participant in a fraudulent scheme became the narrative reflected by the media. When the jury ultimately found against Dummar, newspaper, magazine, and television coverage everywhere presented him thusly.

“When I would go looking for a job, they had two reactions; one was ‘Oh, you’re a liar, you’re a forger, we don’t want your kind around here.’ And the other reaction was, ‘You’re going to inherit all those millions of dollars, you don’t need this job. We want someone who’s going to stay with us for years.’”

“It destroyed my life. It really did,” Dummar trails off, sentimentally.

TOUCH AND GO

Melvin Dummar’s story may have ended there, though, by chance, a retired FBI agent named Gary Magnesen heard about Dummar’s case and took an interest in the events, eventually launching his own private investigation into the story of the will. Magnesen—with the help of the two decades since Hughes’ death—was able to find people and stories that chipped away at the narrative casting doubt on Dummar’s story.

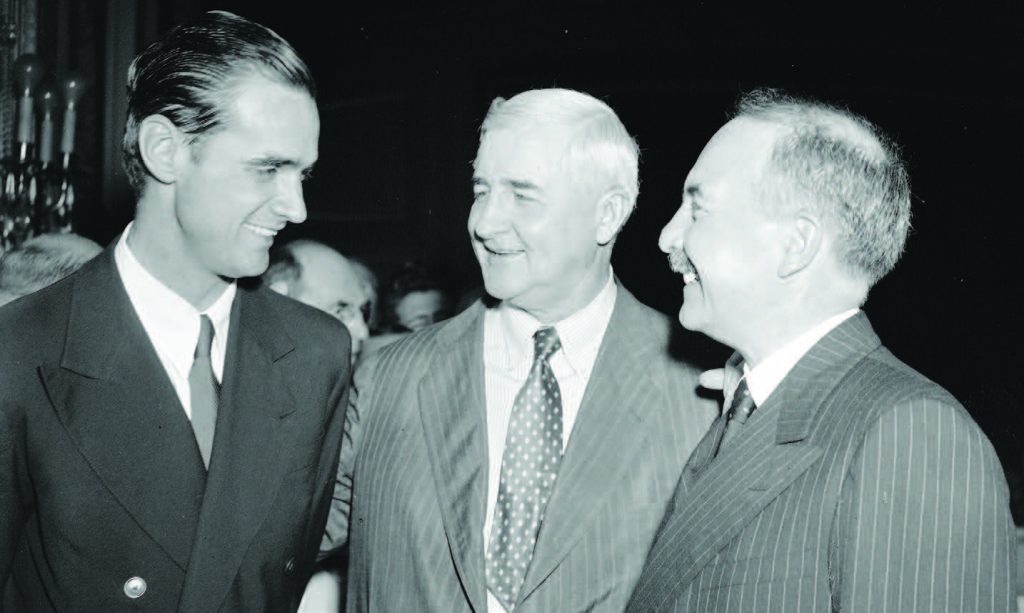

Central to the belief that Dummar’s story was false was the common knowledge Howard Hughes lived as a recluse and never left the Sands Hotel. But after the billionaire’s death, former employees came forward with instances and anecdotes of Hughes leaving.

“One guy told me, ‘I know he [Hughes] left, because I was the driver,’” Dummar says.

Most notably, a man named Robert Deiro came forward saying he had worked directly under Hughes, as director of aviation facilities for Hughes Tool Company and manager of the Hughes-owned North Las Vegas Air Terminal [now the North Las Vegas Airport].

Deiro has described flying Hughes to the Cottontail Ranch on multiple occasions to see a particular worker.

“He said, ‘[Hughes] had a favorite girl that used to work in the Cottontail Ranch named Sunny.’ This girl supposedly moved from Ash Meadows, and that was his favorite girl,” Dummar explains, describing an early conversation with Deiro.

Dummar admits that after encountering so many people who claimed a connection to the events between he and Hughes, he was at first skeptical of Deiro.

“He talked about the dirt runway coming right up to the back of the [Cottontail Ranch] building, what he would wear. I knew some of those things he said were true. It wasn’t public knowledge,” he elaborates.

Robert Deiro has described one night in particular when, after flying Hughes to the Cottontail, he fell asleep. Upon waking up and asking for Hughes, he was told his friend had been drunk and asked to leave. Deiro searched nearby, but could not find Hughes. He eventually flew back to Las Vegas without him.

Others would come forward in the succeeding years with stories that would chip away at the case against Dummar’s version of events.

“Leslie King was the first handwriting expert that looked at the will and said it was Hughes’ handwriting,” Dummar recounts. “When it came time for court, she refused to testify because she said she was threatened, that if she testified, she’d be blackballed from the American Handwriting Analysis Foundation.”

Describing the primary piece of physical evidence—the will itself—Dummar describes what seems to be an intentionally blurry management and handling of the document in question.

“They claimed it was destroyed several times. I went and requested it, Magnesen requested it, and they said it was destroyed. Then, miraculously, a few years later they went back and said, ‘oh, it’s in this here lockbox.’” Dummar says.

Gary Magnesen would go on to write two books about his investigations into Melvin Dummar’s claims: 2005’s “The Investigation: A Former FBI Agent Uncovers the Truth About Howard Hughes, Melvin Dummar, and the Most Contested Will in American History,” and 2015’s “Stolen Justice: The True Story Behind the Howard Hughes Will.” Both contain information that he found or that has surfaced since Dummar’s original trial and expresses Magnesen’s belief that the Mormon Will is authentic and valid.

Today, Melvin Dummar sells real estate throughout Nevada. “I couldn’t get a job, so I had to create my own job.”

On the day I met with him, he was returning from showing some land in Dyer, a commute that had him drive right by the crumbling remains of the Cottontail Ranch and the dirt road where he stumbled across a bloody and trembling Howard Hughes on that frigid December night.

“People ask me when I’m going to retire. I say I guess when I fall over. Even now, I have cancer for the third time. I didn’t think I’d make it past 2002, because I had Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma,” he explains.

While talking, Dummar emphasizes that he feels no ill will toward Hughes.

“I think he genuinely tried. I wrote a song about it:

Thank you, Howard, for leaving me something

But all I ever got was frustration, and I’ll never live it down

I don’t care what the papers say, I never did anything wrong

But I’ll never see the millions you left me, but I know you sang my song.”

Melvin Dummar doesn’t sing as often anymore, and to this day, he remains the only person named in Howard Hughes’ will who has not received anything as a result. He describes a life lived independently, almost out of necessity from the ensuing opinion of him after the trial. Subsequent legal appeals have all been denied. Despite his age and past health, he remains in turns fiery, sentimental, empathetic, and candid.

When I ask him if he ever did learn to fly, he answers without hesitation.

“One of my brothers, he used to have his own plane so he would take me flying. I’m sure I could still take off and land…” he says as he smiles.

Editor’s Note: Melvin Dummar passed away on Dec. 9, 2018.